On a cool fall morning last week, lawyers, defendants and court employees drifted through security into D.C. Superior Court. Outside Courtroom 314, a different constituency waited: family and friends of Philip Cooney (MSB ’10), the Georgetown student charged with bias-related assault by the Metropolitan Police Department. It was a strange reunion for Cooney’s supporters, many of whom had attended the arraignment where he pled not guilty. They hugged and chatted as they filed into the sleepy courtroom. Cooney’s friends were there, some from the rugby team, as were students from a Georgetown business law class. When Senior Judge Susan Winfield turned her attention to Cooney’s case, his experienced criminal attorney, Danny Onorato, seemed to know more about the circumstances of the investigation than the U.S. Attorneys prosecuting the case. Onorato made his motions, demanding information from the government about a controversial Facebook identification and drawing, at times, terse questioning from the judge. He rejected a plea deal that would eliminate the hate crime enhancement, indicating confidence in his client’s innocence. Both sides expect a jury trial. Cooney, in his only speaking role, promised to reappear. At the end of the proceedings, the courtroom nearly emptied as twenty-some friends and family decamped for the hallway.

Cooney’s next hearing is set for November 9, the two month anniversary of the assault.

STOP in the name of love: The scene of the September 9th bias-related incident. EMILY VOIGTLANDER

The University didn’t reveal news of the assault until three weeks after it occurred, after students had seen it on the evening news. The administration’s silence incensed the campus Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Questioning (LGBTQ) community. And so, the day before Cooney’s hearing, Georgetown’s Red Square was dominated by a knot of about twenty students in yellow T-shirts bearing the legend “I am.” This was GU Pride, for whom the perception of pervasive homophobia, coupled with a lack of LGBTQ student resources, triggered outright anger when the University’s decision not to publicize a violent anti-gay act seemed like a cover-up. An e-mail from President Jack DeGioia calling for tolerance was, to many, words without action. GU Pride and allied groups launched the Out for Change campaign, demanding mandatory information sessions on LGBTQ issues for first years, new protocols for dealing with bias incidents transparently, the revitalization of the LGBTQ working group and, perhaps most importantly to Pride and its allies, a full-time coordinator for LGBTQ resources.

“Jack has to show us he is the ally he says he is,” Olivia Chitayat (COL ‘10), co-President of GU Pride, said. Later, she would add that “the hate crime did catalyze the campaign.”

Pride set a deadline for the University to commit to their demands: November 9.

A LONG ROAD

The path to November 9, 2007 began in 1973, when, according to Voice archives, a group called the Gay Georgetown Students applied for a Student Activities Commission charter. They were turned down. By 1979, though, SAC recognized Gay People of Georgetown University and Georgetown became the first Jesuit institution to recognize a gay student group—until the administration overturned SAC’s decision four days later, citing the school’s Catholic identity. After further negotiation, GPGU sued the University and then-President Timothy Healy, S.J. for violations of D.C.’s Human Rights Code of 1977, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of “sexual orientation.” The case would drag on for the next decade, featuring cameos by then-D.C. Mayor Marion Barry, who considered denying the University’s attempts to issue bonds, and then-Dean of Student Affairs Jack DeGioia, who denied GPGU permission to hold what would have been the first homosexual dance at a Catholic university in 1986. Finally, in 1987, the D.C. Court of Appeals ruled that Georgetown must give homosexual clubs the same treatment as other student groups.

Tensions simmered throughout the next decade. GU Pride replaced GPGU in the early nineties, and in 1998 the University instituted the safe-zone training program, which gave Resident Assistants, staff and faculty the training to provide support to LGBTQ students. At the end of the decade, an LGBTQ working group was founded to develop new solutions to the challenges faced by LGBTQ students. In the summer of 2001, the working group released a report that suggested, among other ideas, that a LGBTQ resource coordinator was necessary, along with a resource center built along the lines of the Women’s Center, according to Joe McFadden (COL ’02), a member of the working group and former co-President of GU Pride. That same summer, DeGioia was tapped to head Georgetown; he is the first lay President of any Jesuit University and, some suggested later, lacked the legitimacy to interpret Catholic dogma.

When the University was slow to react to the working group’s proposals, Pride began a campaign to see them enacted, agitating on campus with demonstrations, phone calls to campus administrators and negotiations mediated by gay D.C. Councilmember and 1990 Georgetown Alum David Catania (I-At Large). But in the end, the University said no to the resource center, with then-Vice President for Student Affairs Juan Gonzalez writing that, “We cannot create or support a center whose mission would unavoidably lead to advocacy of sexual behavior outside the context of marriage. … Such endorsement would run counter to Church teaching and, thus, University practice.” As a compromise, the University hired a part-time resource coordinator, Chuck Van Sant, in 2002. Part-time resource coordinator Bill McCoy replaced Van Sant in 2004

Since then, LGBTQ issues have only arisen in the campus consciousness after particular examples of homophobia, such as an offensive e-mail sent out over the Boston Area Club’s e-mail list in 2003, or a University basketball mailer that included a picture of a homophobic sign last year. Though McCoy was given his own office in 2006 after Pride petitioned the University for it, he says he does not have the time—he is also the Assistant Director of Student Programs—or the mandate to make changes to campus culture, given restrictions on advocacy by the University.

“Time is the fundamental resource,” McCoy said, explaining the difficult of setting priorities. “It’s reading the constitutions of new student groups versus an e-mail from someone whose roommate has just come out.”

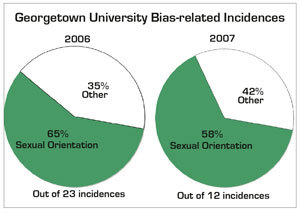

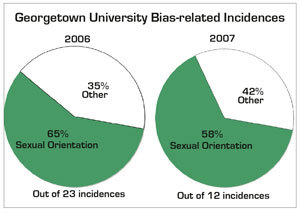

Campus culture reflects the lack of resources for LGBTQ students. Students reported 23 bias-related incidents to the University in 2006; of these, 15 were related to the victim’s sexual orientation. Interim reports from 2007 indicate that seven of twelve reported offenses relate to sexual orientation. McCoy says that he has heard more informal reports of bias-related incidents this fall than any time in his four years at the University, with RAs from three freshmen residence halls seeking him out for counsel.

A FUSE IGNITED

“Look at Macho Man Randy Savage with his tank top. Where are you going, faggot?” More shouts of “fag” and “faggot” followed. Two men began to follow him as he took a left on 36th Street, down a row of houses, many of them occupied by students. One of the men tackled him, punching his head and face. As he was assaulted, he tried to remember his assailant’s face, according to the police report. He suffered cuts, bruises and a broken thumb. Police responded, and he was taken to the hospital for treatment.

Sometime in the next few weeks, police say, a friend of the victim overheard other Georgetown students discussing the incident and relayed the initials from a monogrammed backpack. The victim used Facebook to examine the friend-network of the student with the backpack and discovered someone he identified as his assailant. The victim reported this person to the police, who subpoenaed the suspect’s Georgetown identification photo from the University and put it in a photo-spread of nine students. The victim pulled photo number three—Philip Cooney (MSB ’10), whom the victim had identified on Facebook—from the spread.

Cooney was arrested without incident on September 27 by DPS officers. Local TV news picked up on the arrest—it came shortly after two other gay bias-related crimes in D.C.—and students catching the first new episode of “The Office” were shocked to see a dramatic story so few had heard about. The next day, Vice President for Student Affairs Todd Olson sent an e-mail to the student body, which, without commenting on the details of the incident, said that “Georgetown considers acts of hate and bias in any form unacceptable and antithetical to its commitment to inclusivity. We take seriously any allegation of intolerance within our community.” DeGioia sent out a similar e-mail the next week. But for LGBTQ students and their supporters, it was too little, too late.

In the two weeks following the assault, they would revitalize the LGBTQ working group, rally in Red Square, meet with administrators, attempt to host a town hall meeting but cancel it when DeGioia could not participate and begin a petition drive. It was all part of a campaign to convince the University to accede to their demands for more resources and training. After last Thursday’s rally announcing their campaign and the November 9 deadline, they marched on Healy, determined to deliver a petition and an “I am” T-shirt to DeGioia himself.

As administrators, including Olson, Vice President for Public Affairs Dan Porterfield, Vice President for Communication Julie Green Bataille and Director of Public Safety Daryl Harrison watched, DPS officers formed lines to prevent the demonstrators from entering the building. The chanting students—“Hate Crimes are ridiculous/My Georgetown is better than this”—milled about and asked to be able to send one or two representatives to the President’s office, while students not wearing the yellow Pride T-shirts were allowed into the building. No one seemed to be in charge. The students were eventually able to give their petition and t-shirt to DeGioia’s Chief of Staff, Erik Smulson, and they left. They allege that some DPS officers followed them and continued to prevent their entry into Healy after the demonstration. Administrators said the unusually large security presence was due to a debate scheduled to occur an hour later.

At Cooney’s hearing the next day, Onorato told the court that his client had rejected a plea bargain that eliminated the hate crime enhancement and would have likely resulted in probation. Instead, in preparation for trial, he filed a motion demanding access to any and all documents related to the investigation and possessed by the victim, the police and Georgetown. “There is no physical evidence of any kind that places Mr. Cooney at the scene, other than this suspect identification,” Onorato wrote in a motion.

Onorato is specifically challenging the affidavit that provided probable cause for Cooney’s arrest warrant. Onorato says he found out that the student with the monogrammed backpack was interviewed by police, denied that conversation had happened and said he had no knowledge of the victim’s assault. This information was not included in the affidavit, and Onorato argues that it is “unfathomable” that the police would not include it in their request for a warrant, which led, in his view, to a “wrongful arrest.”

Though he declined to say where Cooney was on the night of the ninth, Onorato said he did commission a polygraph test that his client passed: Cooney answered “no” when asked if he had participated in or witnessed the assault. The former FBI agent who administered the test, Barry Culvert, has administered polygraph tests in several high profile spy cases, according to CNN, and also administered a test to former Congressman Gary Condit during the murder investigation of Chandra Levy in 2001. But Channing Phillips, spokesperson for the District of Columbia U.S. Attorney’s office prosecuting Cooney, notes that polygraph tests are not admissible in D.C. court.

“Philip Cooney did not assault anyone,” Onorato said. In court documents, he described Cooney’s life as “exemplary.”

“We only bring cases where we believe in a reasonable chance of conviction,” Phillips said.

ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN

Bill McCoy, a youthful 27, perches in his office chair. It is a tough time to be the LGBTQ resources coordinator, as the student community he is there to support fights the administration that he represents. It is a fight over what, exactly, his job should be.

Showing their true colors: GU Pride speaks out about the September incident.

KATIE BORAN

“Stuck in the middle is sort of where I find myself,” he said, confessing that the demands of his two part-time positions—he affectionately calls them his “gay and straight jobs”—leave him able to see all too well the concerns of both sides of the dialogue. Though sensitive to the challenges of University bureaucracy, the ability to spend more time and money on forward-thinking projects—expanding safe-zone training to reach a critical mass of students, for instance—would, he said, allow him to have a much larger, and more positive, effect on campus culture.

“There is a pervasive silence at Georgetown,” he said, in part because of a certain perception of the University’s Catholic identity stifling discourse about LGBTQ issues. But McCoy, like other LGBTQ advocates at Georgetown before him, points out that the Jesuit idea of cura personalis means that the University is obliged to care for its LGBTQ community. “We have to do some self-reflection about what we’re doing for this particular group of whole people.”

“Part of the problem is that we tend to think about homophobia and we tend to think about all biases as something that individuals do,” Dana Luciano, an assistant professor in the English Department, said. “This fool over here is going to say something homophobic, this fool over here is going to say something racist. What we don’t do is address the kind of structures that sustain and promote these biases.”

Luciano, a member of the LGBTQ working group, joined other faculty to write an open letter to Olson protesting the treatment of Pride during its protest. In part, it read, “[W]e now feel that, when we participate in working groups or meetings with administrators, we are simply being used as a cover so that administrators can claim that progress is being made … and that the University is not seriously interested in addressing, let alone resolving, the root causes of these recurrent problems.”

Georgetown has a variety of stakeholders, from students, faculty, staff and alumni up to the administration, the board of directors, the Society of Jesus and the Catholic church. Only the administration and the board of directors can actually make binding decisions about University governance, but naturally they must respond to pressures from the various other interest groups. Now, LGBTQ and other students are pressuring for change—at last count, their petition had over 1600 signatures, nearly a third of the student body—and are meeting much less pressure from conservative student and alumni groups than they have in the past; in fact, an informal LGBTQ-focused alumni group is forming to lobby the University. DeGioia is entering his sixth year as a lay president, in a term that many view as largely successful. Could Georgetown be a leader among Catholic schools on LGBTQ issues?

“If nothing else, I’m encouraged by the discussion,” McCoy said. “Am I optimistic that some change will happen? Yes. Am I optimistic that they will get everything that they are asking for? I don’t know that I can say that.”

“I’m certainly more hopeful that any pressure that DeGioia felt to act other than what is in the best interest of the students has dissipated somewhat,” McFadden, who is part of the informal LGBTQ alumni network, said.

Out for Change is planning to escalate its direct action campaign if the University does not make a firm commitment to its demands, inspired and led by veterans of the Georgetown Solidarity Committee’s Living Wage Campaign. The government is preparing its case against Cooney, even as Onorato prepares to defend his client against charges of bias-related assault. November 9 will be one more step towards answering two now intertwined questions: How does Georgetown address LGBTQ issues? And what happened on that early morning in September? And, in the end, what does this all mean for Georgetown?

“I think today’s best and brightest students, whether or not they are LGBTQ allies, straight or questioning, don’t want to be in a homophobic atmosphere. They want to be in an inclusive atmosphere and an affirming atmosphere,” Luciano said. “If Georgetown doesn’t take steps to change their atmosphere, those best and brightest students are going to start to go elsewhere.”