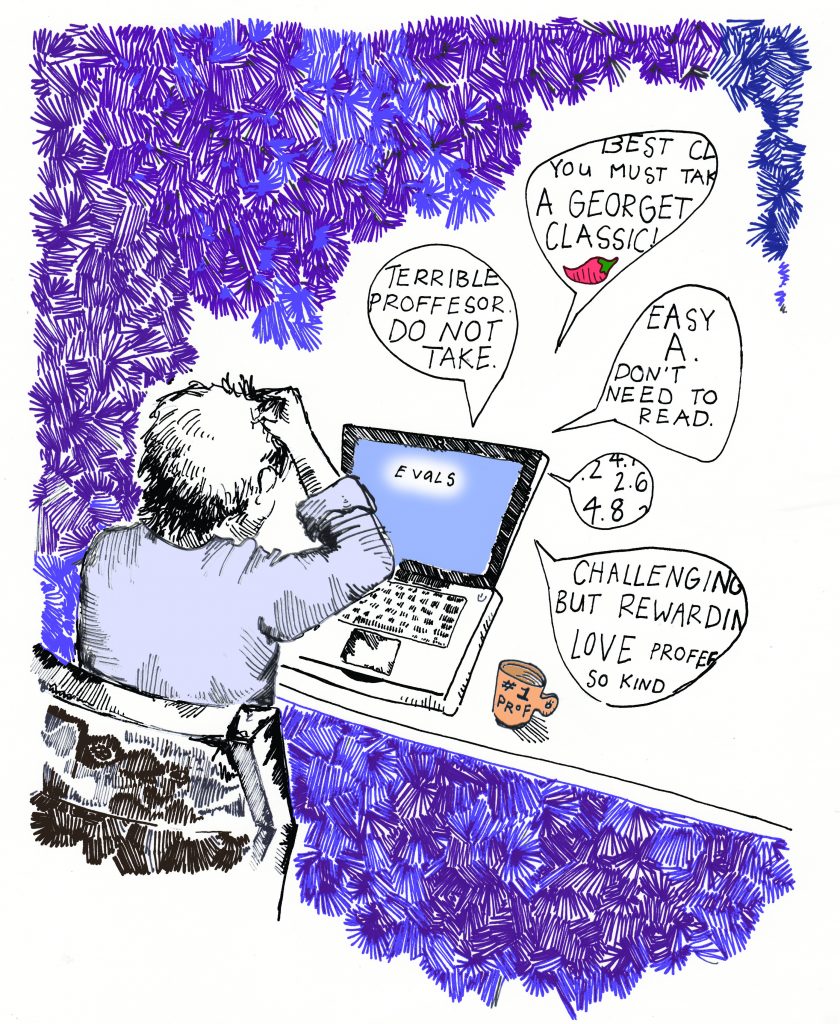

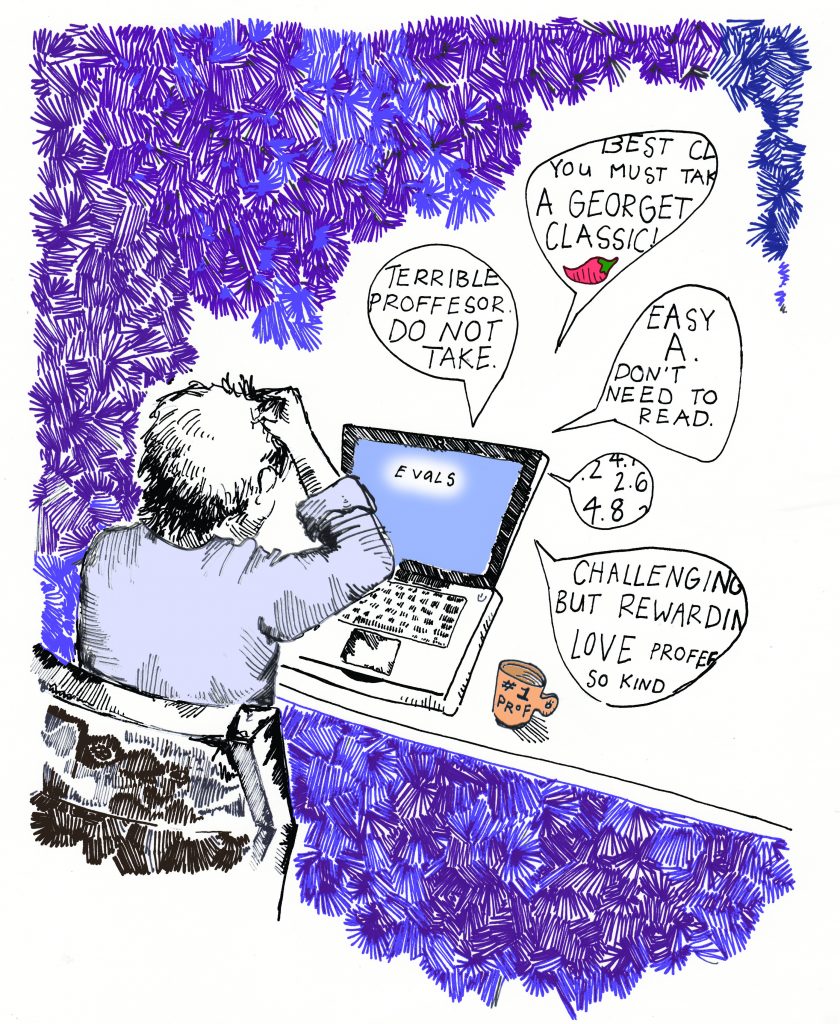

Illustration: Christina Libre

“I WANT YOU,” reads a long-forgotten sign that still remains affixed to the wall of a Car Barn classroom. This sign, and many others like it, are the last remnants of the Office of the Registrar’s campaign in the fall semester to increase the response rate of student course evaluations.

Although these and other humorous signs, along with advertising efforts, have been successful in raising the number of students who submit course evaluations, they do not inform students of what happens after they press submit.

According to Luc Wathieu, deputy dean at the McDonough School of Business, the biggest misconception among students about course evaluations is that they do not know which faculty members actually have access to the different parts of the evaluation. Although quantitative evaluations are made available to administrators, deans, department chairs, faculty, and students, only the course instructors have access to the qualitative comments.

The quantitative portion of student course evaluations asks students to evaluate the course by ranking various aspects including the effectiveness of course materials, how stimulating the class is, how much was learned, and overall evaluations of the professor on a scale from 1-5. The qualitative section asks the same questions about material, learning, and the instructor, but allows for students to elaborate on their numbered responses through written comments.

“Students don’t know this, because when I read evaluations, it’s apparent they think they are writing to deans, but they are really only writing to the professor,” Wathieu said. “Only the professors see everything so that they can learn from the comments. They are always very anxious to hear what the students have to say.”

One of these professors is Manus Patten, who has been teaching in the Biology Department at Georgetown for the past four years. Patten teaches three courses per semester and takes the time to read every student comment he receives. “Reading course evaluations actually just takes a lot out of you,” Patten said. “You get hung up on the negative comments and you feel really bad because at the end of the semester, you’re emotionally drained, you’re tired, and you’d like to think you’ve done something good.”

David Lipscomb, a professor in the English department, also takes each student’s individual comments very seriously, especially in evaluating the success of each of his assignments. “More than anything, I want to make sure that every assignment I had was useful in meeting the specific goals I set for the class,” he said. “It’s important to hear directly from students about what worked for them and what didn’t so that I can adjust the assignments when or if I do teach the course again.”

Although Lipscomb thinks that the written comments are helpful for improving his courses, he has found that the numbered scores given by students about the overall quality of the course and instruction aren’t as useful. “I try to look at the more specific questions about the assignments and material covered. If students aren’t rating assignments as highly, that will raise a red flag,” he said. “But students’ overall ratings of a professor aren’t really helpful. Being liked is a nice thing, but it’s not especially important in terms of what [students] are learning. What evaluations need to get at is how much students are learning.”

Michael Bailey, chair of the government department, similarly uses course evaluations to try to better understand how much students are actually learning in their government courses. “I look at the grades in a course in relation to the amount students have reported to learn,” he said. “If I see high grades, but the amount studied and amount learned are on the low end, then I’ll note that to the faculty just so they know and can improve.”

Bailey, however, does not believe that the course evaluation system is perfect. According to Bailey, faculty should push students to do their best work and they shouldn’t be afraid to tell students when they’re wrong, but the course evaluation system doesn’t allow them to do this. Course evaluations skew the relationship because faculty then are performing a service for students to be evaluated by students. “I worry sometimes that some faculty—maybe their grades get a little higher or they hold back on pushing students because of evaluations,” he said.

According to a faculty survey conducted by the Voice, 81.6 percent of the 38 professor respondents self reported that they have not altered their grading at all due to course evaluation feedback and 63.2 percent have not altered their workload.

Patten has found that the evaluation system isn’t conducive to making worthwhile changes in his teaching. “I have found so little that I have been able to act on,” he said. “I really need context for the negative feedback and getting it anonymously, I don’t know if I can dismiss it as a student disgruntled with his C grade or if it’s a student whose opinion I should value and I should be taking more seriously.”

The Voice’s student survey reveals that 57.9 percent of the 38 student respondents have reported at least once giving a professor lower ratings if they expected to receive a lower grade in a course and 63.2 percent of students have at least once given a professor a higher rating based on receiving a higher expected grade in the course.

According to Patten, the most useful suggestions for improving his course come from one-on-one meetings with students because then he understands the basis for their comments. Therefore, at the end of each semester, he has meetings with students and teaching assistants to ask about how effective his teaching methods were.

Lipscomb also suggested changing the timing of course evaluations in order to improve their usefulness. He explained that end of the semester evaluations have value when a professor teaches the same course year after year and really wants to refine it, but that adding evaluations throughout the semester in order to make course adjustments would be more beneficial to the students currently enrolled.

Lipscomb then added that he would also find it helpful for gauging learning if evaluations were conducted several years or semesters after a student completes a course to keep track of how much information students retain from the course. “We also don’t talk about transfer, how much material transfers,” he said. “I would love to see how transferrable was the knowledge [students] gained, how much they used it in subsequent courses.”

Patten identified biases inherent to the anonymous course evaluation system. He believes that responses are often biased by outside factors that have nothing to do with the quality of instruction. “The difference between negative and positive feedback so often has to do with popularity, likability, and these kinds of things,” he said. “I think I benefit from a lot of the biases that these evaluations reveal. I’m a young, tall, white, male. I don’t get evaluated in the same way that my colleagues do who don’t have those same features.”

Wayne Davis, chair of the philosophy department, has noticed that female professors within his department are attacked in their evaluations in ways that their male counterparts are not. “Female teachers get some of the most hideous comments—about their dress, about their appearance in class, how hot they are or not,” Davis said.

Benjamin Schmidt, a history professor at Northeastern University, recently published an interactive chart online, which reveals unconscious gender biases in professor ratings on Rate My Professors. His findings reveal that women teachers are not only more commonly referred to as “bossy” and “aggressive,” but also are more “ugly” and “mean.”

Interim dean of the School of Foreign Service James Reardon-Anderson acknowledged the potential danger of anonymous student evaluations and explained that this is why student comments are available only to the individual faculty member. “Some of the evaluations can be quite impolite,” Reardon-Anderson said. “When it’s anonymous, some students use poor judgment and there is an inclination to protect faculty just as we try to protect students from deleterious comments.”

On the other hand, Reardon-Anderson also acknowledged the potential benefits of a more transparent system, saying that direct student feedback to department chairs or deans would give students more of a voice in their course evaluations.

According to University Registrar John Q. Pierce, allowing for anonymous responses gives students a non-punitive forum for providing feedback on courses and their professors. Students are able to give open responses and faculty can choose whether or not to respond to them—both without punishment. He suggests that best way to minimize biases within the current system is to increase the participation rate so that data is not heavily skewed by the extremes.

Parnia Zahedi (COL ’15), the president of the College Academic Council, explained that the academic council’s role in course evaluations is to encourage more students to participate. The College Academic Council joins the registrar in sending out email blasts every semester requesting students to give their feedback.

“Back when we had written evaluations, participation was nearly 100 percent because students had to fill out a form in class,” Pierce said. Since switching to the online system five years ago, participation rates among students have fallen to between 60 and 70 percent. “For this process to be reliable, the response rate really has to be over seventy percent,” Pierce said. “The validity of our data depends on it.”

Chair of the Main Campus Executive Faculty Ian Gale said that he has recently assembled an ad-hoc panel of professors, which met for the first time on March 30, to understand different biases that affect the course evaluation system at Georgetown. Studies at other universities have noted correlations between evaluation scores and the professor’s age and the grades awarded in a course. “If you have a younger professor and higher grades in a course, then the evaluations are going to be higher,” Gale said. “But it’s unclear whether the students are learning more or if younger teachers are just teaching to the test.”

According to a preliminary analysis recently conducted by the Office of the Provost at Georgetown over the past few months, there are already a few factors that clearly affect evaluations at Georgetown. “We found that courses with high mean grades usually generated higher evaluations of the instructor,” Provost Robert Groves wrote in an email to the Voice. “We further found that small-enrollment courses tend to generate higher student evaluations.”

Groves wrote that continual analysis of the course evaluation process over time and across departments and schools is helpful in terms of understanding how to improve the system and change its design in the future.

“This is important because raises depend on these results and so do rank and tenure decisions,” Gale said. “Our goal is to make more information available so you know that you’re treating people fairly in these big decisions.”

Administrators, department chairs, and deans use the quantitative course evaluations in merit review, the annual performance review of faculty, which affects their salaries, tenure and promotion cases, and adjunct re-hiring decisions.

“From an administrator’s point of view, when we assess the performance [of a faculty member], we’re pretty much looking at those questions that give an overall evaluation of the faculty member and that indicate the availability of the faculty member,” Reardon-Anderson said. “Those are the most crucial areas.”

The other questions on the evaluation are useful, Reardon-Anderson said, but when evaluating faculty, the most important thing is to make sure that faculty members are good instructors who available to their students.

Ori Soltes, a full-time non-tenure line faculty in the theology department, however, does not think that evaluations have any impact at all on tenure decisions. “My sense is that student input isn’t taken as seriously as the university would like to pretend it is,” he said.

“A number of years back, I had applied for the full-time tenure line Jewish studies position in my department. … My classes were packed, overflowing, over registered, my evaluations were superb, my recommendations were superb, I had students without my even knowing it who wrote letters to my department, but I did not get the position,” Soltes said. “It had nothing to do with evaluations, well with anything really, except what the then chair thought was the wise thing to do for the department. He knew that if I didn’t get the position, I would stick it out and I did.”

Wathieu asserts that, in the MSB, research is the most important thing for faculty members seeking a promotion. “We want thoughtful professors who contribute and are not just diffusing knowledge, but also creating it. We want professors to be passionate about a particular topic,” he said. “But, if a professor has consistently low ratings and is not teaching well, it becomes a problem. Anyone who gets promoted must also be a good teacher. Usually, good researchers are good teachers.”

According to Davis, professors in the philosophy department spend the first few years learning and improving based on their evaluations so that by the time they’re up for tenure, they are good professors. Following that, Davis said, professors usually maintain their high evaluations.

Even after faculty are tenured, Reardon-Anderson said that administrators still analyze the evaluations carefully to make sure that professors are performing at the highest level. “Administrators pay very close attention to the results,” he said. “They continue to review tenure professors, but it’s especially important for adjuncts.”

Adjunct professors represent 42 percent of all faculty at Georgetown’s main campus, according to Director of Media Relations Rachel Pugh. “Adjuncts are hired one semester at a time,” Reardon-Anderson added. “You want to always check up on them to make sure your department is hiring the best adjuncts.”

Soltes, however, argues that these crucial decisions aren’t actually based on evaluations. Rather, he argues that they are made on the basis of how large course enrollment is and the overall needs or the department. “If they’re eager not to rehire an adjunct, then they might bring up negative course evaluations, but as far as I can tell, you can have glowing evaluations that go completely ignored,” he said.

Reardon-Anderson contends that administrators do in fact matter. “When I was a program director, I either did or did not renew faculty on the basis of evaluations so I can tell you firsthand that they do matter,” he said. “Students here can have a big impact and I’m not sure that they know this.”

According to Zahedi, when students don’t fill out their course evaluations, they’re missing an important opportunity to have their voices be heard by faculty. “I do wish that more students were taking time to fill out their evaluations because not only are professors reading them, but deans and administrators are paying attention to them as well,” she said. “What we say on them is more important than we think.”