The biggest story of the MLS offseason was the addition of two expansion teams, Atlanta United and Minnesota United. The two clubs have had differing success, with Minnesota leaking goals and Atlanta scoring plenty in the teams’ respective inaugural seasons, and this offseason there are still more clubs to follow. Los Angeles FC is set to enter the league next season, with plans to build a new stadium in Exposition Park, unlike Chivas USA, who came into the league sharing the Home Depot Center (now StubHub Center) with the Galaxy. It is widely believed that David Beckham’s Miami plan will be team number 24.

This is no different from other major American sports leagues, with the Big Four leagues having either 30 (MLB, NBA, and NHL) or 32 (NFL) teams each. With the MLS, though, it’s not quite that simple.

The Big Four leagues are far and away the leaders in their respective sports. Salary cap restrictions for each are in place to prevent (in theory) the existence of super teams. None of the four need to worry about salary restrictions affecting the league’s competition on the international stage.

In Europe, a league with 28 teams is unthinkable. Very few leagues even have more than 20, with the Championship, League 1, and League 2 in England the only leagues with 24. 18 to 20 teams seems to be the magic number, with Germany’s Bundesliga, Italy’s Serie A, England’s Premier League, Spain’s La Liga, France’s Ligue 1, and Portugal’s Primera Liga all fitting this size.

Beyond rules about maximum Designated Player contracts and salary caps, the MLS is falling further behind because of its expansion efforts. While the league has made strides competitively, a look at its stars shows there is still a long way to go.

NYCFC was carried to the Eastern Conference’s number two seed by a 34 year-old David Villa, who scored 23 goals en route to a league MVP award. The 2015 league MVP, Sebastian Giovinco, lit the league alight once again in 2016, scoring 17 goals and adding 14 assists while missing eight of Toronto’s regular season games and adding four goals and two assists in Toronto’s Eastern Conference championship campaign.

Despite their excellence in the states, MLS stars had previously struggled overseas. Giovinco couldn’t get minutes at Juventus behind strikers Carlos Tevez, Alvaro Morata, and Fernando Llorente. Villa was beyond his peak in Spain, as Atletico Madrid hardly put up a fight to keep La Roja’s all-time leading scorer, letting him and Diego Costa leave in the same summer. Instead of holding onto Villa to lead the line, El Atleti chose to bring in Antoine Griezmann and Colombian striker Jackson Martinez. Even Didier Drogba, when he wasn’t feuding with Montreal, revitalized the Impact and nearly dragged them into an MLS Cup Final against Portland. Drogba moved to Montreal after returning to former club Chelsea after short stints in China and Turkey. However, it was only to provide cover for Costa when then-Blues manager José Mourinho couldn’t trust Loic Remy as a rotation player.

These three players, one of whom still can’t get a sniff for Italy and the others past the peak of their powers all carrying their teams in a Lionel Messi-esque fashion shows that the talent in the MLS is incredibly uneven. The superstars that carry the league and drive ratings forward are all attackers, and the most recognizable name to come to the league on the defensive side of the ball is 37 year-old Tim Howard, a man who was dropped at Everton for Joel Robles, former Wigan FA Cup hero but nowhere the level of the top Premier League goalkeepers.

Even the Chinese Super League, a league whose quality of play is often scoffed at and has restrictions on the number of non-Asian and international players a team can employ and field, threatens to become a more attractive league than the MLS. Last winter, Martinez made the move to the Far East from Madrid, and Alex Teixeira chose to join Jiangsu Suning from Shakhtar Donetsk despite rumored interest from Chelsea.

Maybe expansion will add more designated player slots to attract more high profile players, but it could backfire on the league. A league that still struggles to enhance its reputation prevented Antonio Conte from considering Giovinco and Italian legend Andrea Pirlo for his Euro 2016 squad.

Deciding to leave a more reputable league for MLS is risky for even a national team stalwart. The lowered competition can leave players less sharp for the demands of international play. For a young player on the fringes of the national team picture, the move to MLS could derail an aspiring international career. This is already an issue with the league at 20 teams, and diluting the talent across eight more only worsens the effect.

Major League Soccer is largely star driven, and designated players play a large part in driving ticket sales. The focus on growing the league’s profile, however, has left American talent development behind. The hottest American prospects, like Christian Pulisic and Bobby Wood, play overseas, while the MLS struggles to produce similar types of players. From those who stay home, the Los Angeles Galaxy’s Gyasi Zardes has had inconsistent performances with the national team, while the Seattle Sounders’ Jordan Morris has seen much of the same, even missing this past summer’s Copa America Centenario squad for the US.

While the American squad under Klinsmann used increasingly more MLS players, most of them were players who returned to the league after spells in Europe. There are no Landon Donovans coming through the ranks of the league. With additional teams diluting rosters, national team prospects will lack the requisite competition, in practices and in games, to propel the US further along in the international scene.

The biggest issue with the size of the league, however, is scheduling. While most leagues play a double round robin format where each team plays every other team home and away, the MLS is different. The teams each play a 34 game season in a 22 team league, so some teams play each other only once, while others play each other three times. It’s an uneven schedule that unfairly judges the league’s teams because strength of schedule may vary between them.

Then the teams play in the playoffs and ultimately find their champion, using the typical American playoff format. There are, however, other competitions. The clubs play in their own domestic tournaments, with the US Open Cup and Canadian Championship as domestic cup competitions available for the teams in their respective countries. Both conference champions in MLS are also awarded spots to the CONCACAF Champions League (which creates another issue with the strength of schedule disparity).

The MLS Cup Champion is also awarded a CCL spot, which doesn’t necessarily depend on the uneven schedules, but on the MLS playoffs. However, the playoffs include six teams per conference, 12 of the 22 total teams, it creates an incomplete picture of who the best teams in MLS are. To masquerade a team that got hot at the right time as one of the “premier” teams in the MLS in a year-long, confederation-wide competition does a disservice to the league and to the competition as a whole.

To give MLS its best chance in the CONCACAF Champions League, the league would be better served to adopt a traditional, single table format. Even if the league prefers its playoff format, Liga MX has had success with a single table format followed by the liguilla, or little league an eight team knockout tournament to determine the champion. But a single table format for MLS creates more balanced schedules and assures that the teams who make the playoffs at the end of the season are truly the league’s best.

However, a 28 team league creates other obstacles with scheduling disparities. There are simply too many teams for them all to play each other twice (I’m considering twice since ideally teams would play each other home and away). Therefore, as the league grows, the MLS needs to find a way to whittle itself back down to a manageable size.

As we have seen with Minnesota United, even teams in the lower divisions have strong support. To think that Minnesota is an isolated case is understandable, since the lower leagues in the United States and Canada get hardly any publicity, mostly because the clubs that play in the second tier have no chance of earning their way into MLS. Promotion-relegation may be completely un-American at its core, but it’s the way to move the league forward.

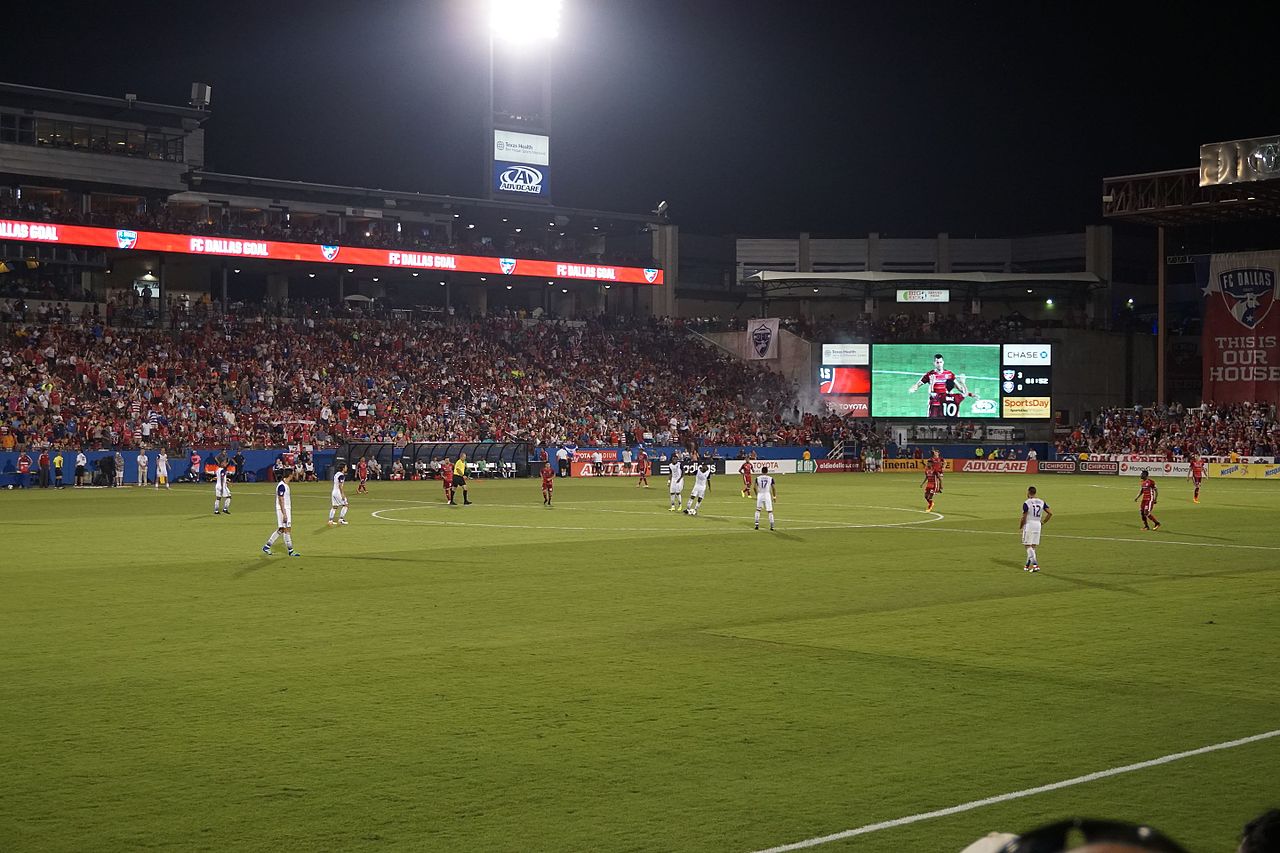

Keeping MLS the way it is disincentivizes competition. Teams that know they’re going to fall below the magic “red line” of the playoffs have no reason to get better and keep competing. Otherwise, they’ll fall lower in the designated player allocation order and have a worse pick in the MLS SuperDraft. Sure it might be good for youth development, but teams in MLS have even been successful while developing their youngsters (just take a look at FC Dallas).

In adding the fear of a drop for the clubs that finish at the bottom of the table, the league would send a clear message: We want you to play competitive soccer no matter how many points you have. The young players that break into the first team would do so under heightened competition and play in meaningful matches, not just because a manager decides that the season is a lost cause and they may as well let the youngsters try things out.

It also makes the lower leagues of American soccer more exciting. More emphasis would be put on development at those lower clubs, and more support would come through now that the chance of MLS glory would be available for every team in the country, not just Don Garber’s select 28.

For the international managers, promotion-relegation shows that the league is ready to take cthe next step and that the players there are ready for the demands of the international game. MLS is unlike any other league in terms of the differences in weather and travel distances that teams face. The physical toll that travel takes on the body is something the MLS players are already used to, so traveling between countries and playing games shortly after wouldn’t affect them as much as it would their counterparts. Managers fear that the players simply don’t have the skills to compete, even if they are more physically able to handle the travel demands of international play.

As long as the league decides to keep growing, the quality of play won’t improve; it will deteriorate. For MLS to take the next step, it needs to escape the American sports league archetype and make a statement. It needs to be a soccer league, or it will never be elite.