When I was in the fifth grade, Jake, the boy who sat in front of me in math class, turned around randomly and asked me, “Do you know Putin?” Without awaiting my response, he answered: “He started the Cold War,” (accompanied by exaggerated shivering). At age 10, I had little awareness of the Cold War, Vladimir Putin, or any tensions between the two countries that define my identity, and the comment brought a lot more amusement to my parents than to me.

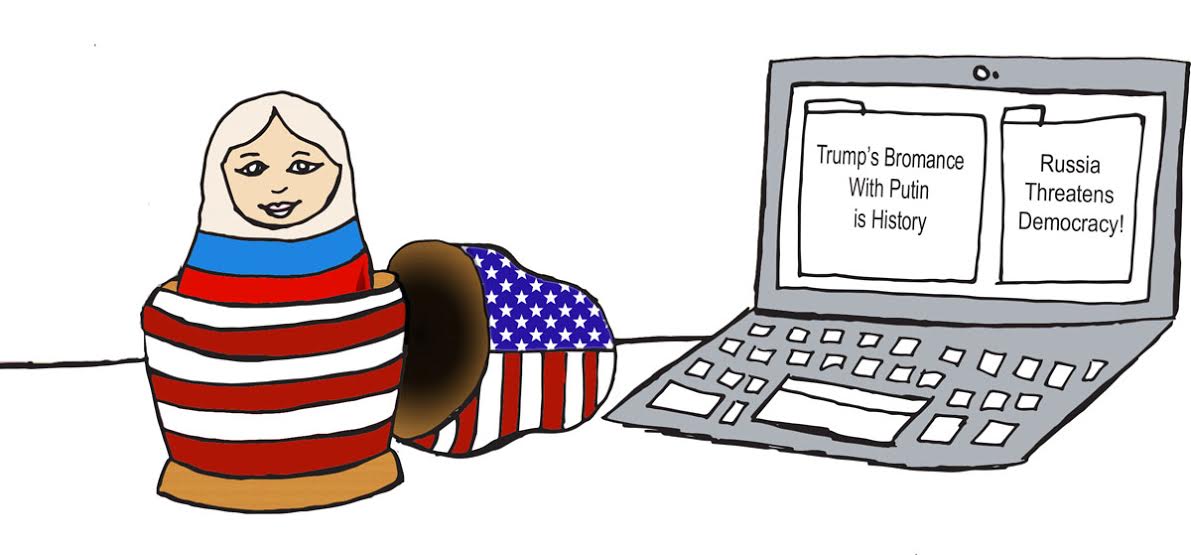

Ten years later, Putin has remained an active figure in the Russian government and has become even more of an active figure in my social life. Rarely does a week pass without seeing at least a dozen inflammatory articles featuring his name, and rarely does his name remain unspoken in my first encounters with other people. However, joking references to vodka, an affinity for cold weather, bears, and more recently, President Trump, are equally common, if not more so, than references to Putin himself.

When I was younger, like many children of immigrants, I revealed little of my Russian-ness to those around me. I was reluctant to explain to my friends that I got presents on New Year’s from Ded Moroz instead of on Christmas from Santa and was embarrassed by the borschts and pilafs that I ate for lunch, envious of my friends’ Lunchables and Scooby-Doo gummies. It’s not that I was ashamed of my nationality—I just didn’t feel like that part of my identity was worth emphasizing or sharing.

As I got older, I became more attached to my heritage, more open about it, and consequently more annoyed by stereotype-inspired comments. I became more conscious of their underlying context as I learned both the Russian and American Cold War narratives. A girl in high school said to me that Russia was “basically a third-world country,” and I was insult-to-my-family-name levels of offended. Of course, almost everyone with a cultural or ethnic background that deviates from the “I’m 1/16 every European country” norm has experienced similar unsolicited comments, inaccurate assumptions, and annoying jokes.

However, in the past decade, the general norm has started to change. “Diversity” has become a magic word, devoid of a concrete definition but nevertheless desired. Elite colleges and businesses alike tirelessly try to attract unique and underrepresented individuals. Despite recent examples of the opposite in our current government, America has made great progress in accepting and celebrating what was once unanimously considered the “other”—the legalization of gay marriage and increased representation of people of color attest to this. And yet, attitudes towards Russia and Russian people have followed an opposite trend. “Russia” has become, now more than ever, a dirty word both in the press and in the minds of Americans.

“Become” is probably the wrong word, since the animosity between these two nations originated long before the Trump-Putin memes of 2017. But at the same time, tensions are higher than they have ever been since the end of the Cold War, translating directly into hostility on a cultural and social level.

Headlines like “Trump’s Bromance with Putin is History,” which seem like they belong in The Onion, are normal and common in established publications. Movies as different as The Muppets Most Wanted and A Good Day to Die Hard show that unapologetically nefarious Russian villains are still welcome in every genre, even though characterizing story villains by their ethnicity is generally viewed as prejudiced and wrong. When James Clapper, the former director of national intelligence, explicitly revealed his prejudice, stating that Russian people are “genetically driven to co-opt, penetrate, and gain favor,” no one blinked an eye, despite the quote’s appearance in numerous news outlets.

We all strive for social success and belonging, and for people with multicultural, multiethnic backgrounds, this often includes making a certain sacrifice: assimilation in exchange for relating more to your friends’ interests. In the American “melting pot,” this sacrifice could potentially be smaller, as people in this heterogeneous country can share their cultures with one another. But what happens to cultural exchange when your country of origin immediately conjures up negative associations?

When I watched Coco, a new animated film about the Day of the Dead celebrations in Mexico, what amazed me most was how well it integrated elements of Mexican culture, humor, and language into an American movie.

Clearly, a cartoon about Mexican culture does not signify the disappearance of the very real prejudice, violence, and intolerance that Mexican Americans and other cultural communities still face. Nevertheless, it does demonstrate an effort towards mainstream understanding, a sentiment that I wish applied to Russia. Just like the United States, Russia is a country with a rich cultural, political, and intellectual history–it’s more than Trump’s “secret birthplace.”

As we strive to eradicate prejudice and cultivate respectful, curious, and impartial exploration of other cultures, we must remember the importance of these efforts with regards to countries we might initially view as adversaries. Ironically, in the age of information and interconnectedness, we sometimes desperately lack the understanding and empathy that we have the potential to access.

Today, I often feel anxious about the state of U.S.-Russia relations, and while I have no power over that, I can foster communication and cultural exchange in my own community. I hope that Jake from fifth grade, and all those like him, will somehow stumble upon this and give it a read.

Listen to the accompanying podcast, Fresh Voices.

Image Credit: Lizz Pankova