50 years ago, the National Portrait Gallery opened its America’s Presidents exhibit, which has since become one of the Smithsonian’s landmark tourist destinations. As the Portrait Gallery celebrates its history, it has also established a space to reflect on the American history of portraiture. Unseen: Our Past in a New Light opened in March and features the work of Titus Kaphar and Ken Gonzales-Day, which calls attention to those women and men most often exempted from or misrepresented in American portraiture. While Kaphar’s portraits powerfully manipulate the medium to communicate racial and cultural oversight, Gonzales-Day’s photography visually fails in conveying his otherwise engaging message.

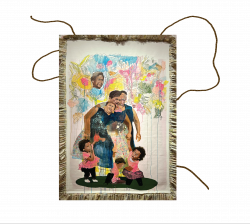

The Unseen exhibit is meant to draw attention to the stories that the National Portrait Gallery cannot tell through its exhibitions, and Titus Kaphar’s paintings expertly visualize the repression of those stories. Kaphar disrupts the traditional style of portraiture—and the histories they tell—by physically destroying classic images. In one striking piece titled “Behind the Myth of Benevolence,” Kaphar shows a portrait of Thomas Jefferson hanging half off the canvas, as if it was ripped from the wooden frame. Sally Hemmings peeks from behind the destroyed portrait of her master, and the father of her children, to stare at the viewer. Kaphar literally tore back the curtains of Jefferson’s supposed benevolence to reveal the dark truth of his slave ownership and relationship with Hemmings.

But “tearing” the canvas off the page is just one of many ways that Kaphar destroys our concept of portraits; he cuts, flips, stuffs, and splashes paint as well. In “Shred of Truth,” Kaphar tears the portrait of Andrew Jackson to hanging shreds, which he then splays and tacks to the walls to the side of the painting, mimicking the destruction that Jackson caused Native American communities by promoting the Trail of Tears. In another piece entitled “Her Mother’s Mother’s Mother,” Kaphar cuts the image of a white woman holding a black child out of the canvas and lets it hang below the canvas, like a peeled back flap. While the pair look at the viewer upside down, a black “mammy” peers through the silhouette left behind, reminding the audience of the topsy-turvy racial relations between white mothers, their children, and the black “mammies” who raised them. By physically disrupting and destroying these images, Kaphar mirrors the destruction of black history and memory, in all its violence and aggression.

Not only does Kaphar deconstruct our current understanding of portraits, but also he draws attention to the ways in which the medium has been scrubbed of controversial imagery. Beyond the “mammy” imagery, Kaphar highlights the erasure of mixed-race family structures in “Civil Union,” where a mixed race couple is literally white-washed out of the portrait with a disruptive layer of white paint. He also physically interrupts images of black Americans in his “Portraits in Tar” of Billy Lee and Ona Judge, who were two of the most well-known slaves of their time, famous for their service to George Washington during the Revolutionary War. Stopping just short of normal portraits, the faces of Lee and Judge are replaced by a textured caking of tar that recalls the historical harm done by the erasure of black imagery.

Much like Kaphar, Ken Gonzales-Day’s work attempts to expose the erasure of racial minorities from American portraiture, but, unlike Kaphar, Gonzales-Day’s presentation is disappointingly lackluster. The majority of Gonzales-Day’s exhibit—two rooms entitled “Naming” and “Distance”—is populated with images of busts and statues that he staged against black backgrounds. Gonzales-Day captured the images in order to show the beauty of racial difference in America and the many ways in which it is shown in sculpture. Though historically interesting, these photos leave the viewer wondering why the busts themselves were not curated and shown, especially since they are owned by the Smithsonian and therefore available for display.

In another puzzling presentation, Gonzales-Day photographs Hiram Powers’ statue “America” facing away from the camera to imply the national abandonment of racial equality when the statue was created. Not only is this two dimensional rendering of another artist’s three dimensional artwork visually boring, it is also utterly incomprehensible without the accompanying informational material. In his piece “Untitled,” Gonzales-Day captures the statue of a Native American man across a long frame from a traditional marble statue of a faun to symbolize the face-off between Native American and white civilization. Again, it is unclear why Gonzales-Day photographed these statues, instead of simply curating a display of the statues themselves. These problems beg the question of whether this portion of Gonzales-Day’s exhibit is artistic at all, or if it’s just a half-hearted repurposing of another artists’ material.

The third part of Gonzales-Day’s work is only marginally less troubling. In the “Absence” section of Gonzales-Day’s work, he has edited historical photographs of lynchings to erase the bodies of the victims from the photos. The artistic purpose is clear: to remove the physical evidence of racial violence ironically calls attention to the erasure of that history. However, in the process of chasing this philosophical goal, Gonzales-Day removes the most arresting element of the lynching scenes. All the viewers are left with is a room full of photos that show southern white men standing next to trees. Though mildly interesting when viewers know the purpose of the artwork, and in spite of the noble motivation behind the exhibit, the photos are stale and visually uninteresting.

In artwork, form must fit function, and, in this respect, Kaphar and Gonzales-Day are almost polar opposites. Kaphar’s work, from the physical way in which he destroyed the traditional medium to way he reveals new imagery behind shrouds and curtains, ultimately succeeds in destroying tradition to rebuild an inclusive narrative. Gonzales-Day, on the other hand, destroys his visual message in the very process of establishing it, indicating his form and medium is poorly suited for his purpose. As artists look toward creating new aesthetic narratives that fairly represent others, they should remember that no matter how inspiring their message may be, form still matters. In art, the thought isn’t all that counts.