“Can a man serve God faithfully and posess slaves?” Brother Joseph Mobberly, S.J. asked in his diary in 1818. “Yes,” he answered. “Is it then lawful to keep men in servitude? Yes.”

The Jesuits of the Maryland province had always relied on plantations to support their ministries. The estates were extensive, totaling 12,000 acres on four large properties in Southern Prince Georges, Charles and St. Mary’s counties, and two smaller estates on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. In 1634, when the Jesuits arrived in Maryland, Lord Baltimore awarded them quasi-estates in which they were permitted to live off the rent of tenant farmers. However, as University Dean Hubert Cloke explains, “The system was totally antiquated and romantic, not related to reality, and they realized they were not going to make any money.” So, the Jesuits turned to indentured servants, English men and women who worked the land for set terms in return for the passage from England to Maryland. But as working conditions improved in England, the supply of indentured servants dropped and the Jesuits once again found a new way to work the land. By the 1680s they relied upon a fully developed slave system.

Compared to other plantation owners in the area, when it came to slavery, “The Jesuits were no better or worse,” according to Cloke. Many of the slaves had been gifts from wealthy Catholic families to sustain the Church. The abolition of slavery was not an issue in the area until the early nineteenth century, when Georgetown’s Jesuits became deeply divided over the issue of slavery.

“But they were not conflicted in the way you would want,” Cloke said. “They were conflicted over what to do about the threat of abolitionists.”

In a generational divide, an older group of Jesuits, mostly European born, felt a patriarchal connection to their slaves and were unwilling to sell them. A younger, American-born group, a minority, felt that the money invested in plantations should be spent on institutions in cities like Philadelphia and New York with their rapidly growing Catholic populations. It seems neither faction had any particular moral quandaries with the six plantations and the nearly 300 slaves owned by Georgetown’s and Maryland’s Jesuits.

This rift is just one of the things American Studies students learned when history professors like Cloke and Emmett Curran introduced the Jesuit Plantation Project into the American Studies curriculum in the spring of 1996. The project involved students transcribing and digitizing hundreds of documents from the Jesuit’s Maryland Province Index recording the Georgetown’s Jesuits’ complicated relationship with slavery.

With only two exceptions, all the higher-ranking Jesuits in the province during the time were foreign-born and of the older faction. Since only U.S. citizens had temporal jurisdiction, foreign Jesuits had no authority over the Mission’s estates.

This meant that a younger group of American Jesuits, a minority, controlled the destiny of the estates, and this group wanted to end slave operations.

“They considered the plantations and slaves as a losing business enterprise and thought the Society should rid itself of both plantations and slaves,” Curran said.

Abolitionists presented an economic rather than moral problem for these Jesuits. With a growing abolitionist presence in Maryland, some of them feared a devaluation of their property, their slaves. Maryland was a state in which slavery had a tenuous hold, the economy was no longer driven by slave labor. According to reports, the general debt of the mission was close to $32,000 by the 1830s, a large sum for the time.

“It was not a market for growing crops, but for growing slaves,” said Cloke. The real money was to be made not from the work a slave could do in Maryland, but from the hugely profitable business of selling the slaves downriver.

In 1815, Brother Joseph Mobberly, S.J. wrote a letter to John Grassi, S.J., the president of Georgetown College, listing three major reasons to sell the slaves. He wrote, “It is better to sell for a time or get your people free … Because we have their souls to answer for.” He then went on to explain that the slaves had become more difficult to govern, and he believed this to be the result of a growing abolitionist movement. Finally, in an extensive table of expenses, he concluded that the slaves should be sold because, “We shall make more and more to your satisfaction.”

Brother Mobberly, who served as an overseer on one of the estates, kept an extensive diary giving a bird’s eye view of the tension the Jesuits felt surrounding the issue of slavery. His diary explores the tension between Catholics, an already persecuted group, and the Presbyterians, Baptists, Quakers and Methodists who were outspokenly opposed to slavery. Mobberly, like other Jesuits, came to feel threatened and saw the issue as a Catholic-Protestant conflict. Involving everything from the Bible to Thomas Jefferson, Mobberly’s diary defended slavery. He explained that Abraham owned slaves, and wrote, “Abraham had God for his particular friend; and we do not read that God ever reproached him for keeping men in servitude. Therefore, it was lawful for him to possess them.”

At the same time, all Jesuits recognized certain basic rights for the slaves. A report from the time demanded adequate fixed rations, half of Saturday to themselves, and the promotion of morality and the administration of the sacraments. However, the report also states that for other slaves, “chastisement should not be inflicted in the house, where the priests live.” In other words, it was acceptable for priests to whip the slaves, just not in the priests’ quarters. Similarly, the document stated that pregnant women should not be whipped.

St. Thomas Manor: over 30 slaves, owned by Jesuit priests, worked on St. Thomas Manor plantation before being sold in 1838. Courtesy Jesuit Plantation Project

“[The Jesuits] did see themselves as different than non-Catholic slaveholders in that they tried to provide for the spiritual welfare of their slaves by allowing them access to the sacraments, such as Eucharist and marriage,” said Sharon Leon, a student who worked on the Jesuit Plantation Project. “Of course, his concern for the slaves was primarily based on his concern for his own spiritual welfare.”

On one hand, Leon said, the Jesuits regarded the slaves as capital, money that would better be invested elsewhere. On the other, there are moments when the Jesuits recognized the slaves’ humanity. In these cases, the issue of emancipation was still not addressed. A letter from Father Francis Neale of St. Thomas Manor addressed a major problem involving “his best Negro hand.” This slave was married to a woman on another plantation, where they had three children. When the wife’s master decided to sell the wife and children; Neale was in a quandary as he could not afford to buy them. “I shall be obliged to sell our Man and not to separate Man and Wife,” he concluded. He never set the man free.

“The contradictions,” says Cloke, “they stop us in our tracks. We operate under the assumptions that we are smarter, that we’d get it right.”

But Cloke doubts this. Slavery as a system was enmeshed in all of the U.S. A recent report on slavery’s legacy by Brown University points out that before 1800, of the 10 million people to cross the Atlantic, 8.5 million of them were enslaved Africans. “Most Americans today think of slavery as a Southern institution,” it states, “but slavery existed in all 13 colonies and, for a time, in all 13 original states.” This peculiar institution was deeply rooted in not just southern, but all of American culture. In Maryland and Virginia, even some free blacks owned slaves.

Early Georgetown students did not have a problem with the Jesuits’ connection to slavery. At the time, many students brought their slaves with them to school, and the college was predominantly populated by southerners.

“There is no way around it. The students voted with their feet in the war,” Cloke said. Over 90 percent of students went on to fight for the Confederacy in the Civil War.

“Georgetown has never not been a Southern school,” Cloke stated, before pointing to the fact that Georgetown hailed itself as a multicultural, international school from its inception. However, Cloke continued, “Georgetown at the time was international because the international students were children of slave traders from the West Indies.”

Jesuits in the Americas have always had an ambivalent relationship with slavery. Jesuits owned slaves in South America; the Catholic Church didn’t outlaw slavery from its missions until 1843. However, the Jesuits of Brazil were expelled from the country by the Spanish and Portuguese empires because their priests were protecting Native Indians from slave-hunters’ raids and undermining slavery. Maryland’s Jesuits, Cloke said, were “a new organization. They had been suppressed and were less revolutionary than their forbearers.”

At a basic level, the Jesuits did not want to create tension in an atmosphere where they were already outsiders.

“Catholics were persecuted, but at least by holding slaves they were like everyone else,” Randall Bass, who worked with students on the Jesuit Plantation Project, explained. “They were working to maintain acceptance where it was hard.”

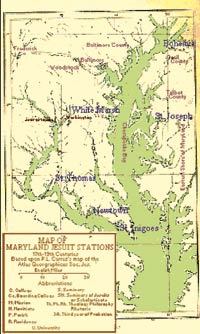

The Maryland plantation: this map shows the Jesuit landholdings around the Chesapeake Bay during the 18th and 19th centuries. Courtesy Jesuit Plantation Project

Fidele de Grivel, a European Jesuit living in Maryland in the 1830s, explained, “The Protestants have, up to now, appreciated us only because of our large estates; if we sell them, they will consider us no better than the Methodist preachers who crisscross the country to accumulate money.” However, money was an issue that none of the Jesuits could ignore.

Leon also points to the related issue of acculturation as practice with which the Jesuits attempted to blend the priests into the life and culture of their local community.

“It usually had good results,” Leon said. “In this case, the unquestioning adoption of the culture and traditions of southern Maryland’s farming communities allowed the Jesuits to pursue slaveholding as a matter of economic necessity, rather than to interrogate the practice and reject it as one that was morally bankrupt and truly unjust.”

In the end, economics won out. Although by the mid 1830s, the plantations were beginning to turn higher profits, this did not placate the younger Jesuits, because the estates were still not seen as sufficient to support the mission. These new Jesuits had no moral quandaries selling their slaves downriver; the felt their investments should be moved to urban centers such as New York or Philadelphia. So, in 1838, at a time when the plantations were at their most profitable, the Jesuits decided to sell their slaves to Louisiana’s ex-governor, Henry Johnson, whose son was a Georgetown student.

Before the sale, the mission drafted “Conditions for Sale,” a set of guidelines to protect their former slaves. They determined that the slaves could only be sold to a plantation, rather than families, “so that the purchasers may not separate them indiscriminately and sell them.” In what reads like a bill of rights, the slaves were promised to be kept with their families, and those with family on other plantations were to be sold to those plantations. Those who were too old or sick to be sold were to be provided for “as justice and charity demands.” Finally, the slaves were guaranteed the right to practice religion. The document also made a demand of the Maryland Jesuits, likely an addition from the new school of Jesuits. The sale’s profit was not to pay off debts or purchases, but “must be invested as Capital which fructifies,” specifically educational centers in New York and Philadelphia.

After the sale, some Jesuits persisted in their interest in the slaves’ well being. Father van de Velde wrote a letter to another Jesuit after a visit to Louisiana and expressed his frustrations. He believed that the slaves had been sold under the condition that they would be able to continue their Christian practices and have “free exercise of the Catholic religion and opportunity of practicing it.” Upon witnessing a lack of Catholic Churches in the area, he went so far as to suggest that the Province of Maryland contribute $1,000 to construct a church near one of the plantations. In another letter, he wrote, “Justice as well as charity require that their former masters should step in and aid other well disposed persons to procure them a means of salvation.”

Curran believes that some of the older Jesuits listed their slaves on the inventory, but warned them of the sale so that they could hide in the woods when the officials came to transport them. Curran explained, “The 1840 census shows a surprisingly large number of younger slaves still on certain plantations, which supports the tradition that some slaves hid themselves then returned to the plantations once the provincial had left.”

With the sale, the Jesuits of Maryland made $115,000 and ended their history as a large slaveholding institution. The money from the sale was, as stipulated, invested in Xavier High School in New York and St. Joseph’s in Philadelphia. Some of the funds also went to finance Fordham University, completed in 1842, one year before the Catholic Church banned slavery. “Much of the funding for these schools came from the ignoble sales,” Cloke said. The schools became a perfect prediction of apostolic interests when they were needed to educate the waves of Irish immigrants to the U.S., where Catholics, due to their religion, would otherwise have few good education options.

“It’s interesting,” Cloke continued, “The young Jesuits, the modernizers were right on in terms of this trend, yet they were the most retro in what they were willing to do to get there in terms of slavery.”

While slavery seems like a distant memory for students at Georgetown today, it would be loathe to forget how this shameful chapter in Georgetown’s history shaped this and other Jesuit universities.

La-Cemeteries is researching all of Louisiana’s deceased governors. One of the most interesting is Henry Johnson, the 5th governor of Louisiana, who purchased slaves for his plantaions and for the plantation of the 3rd Louisiana governor Henry Thibodeaux.

We did not know that a son was attending Georgetown in 1838 as stated in this article. We believe this son would have been about 9 years old.

Is it possible to direct us to a resource that would have this son’s name?

This was a very interesting article that I happened upon as I was researching my Maternal Great-Grandfather’s history, trying to determine when his family arrived in St. Mary’s County, Maryland. I knew the family worked as farmers and thought they may have been slaves and then I discovered this article about the Jesuits in St. Mary’s County. This may explain why I can find him on the 1880 Federal Census as a 17-yo “laborer” living with the Long family rather than his own Holt family in Chaptico, St. Mary’s, Maryland. Thank you for this article and the history lesson on Georgetown, as I was born in Washington, DC and had no idea of Geogetown’s connection to this part of Maryland and slavery.

Added to my collection at The Historical View A WordPress blog.

Man this is some religion!!!!!!

This article isn’t telling us something we blacks don’t already know. Every Institution, this whole country’s wealth and prosperity was built by blacks. This school like this country has a debt that is owed to blacks. We are the only group that hasn’t been paid REPARATIONS. Native Americans, Japanese, and Jews have all been paid.

[…] [S16]. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catholic_Church_and_slavery and https://georgetownvoice.com/2007/02/08/the-jesuits-slaves/. […]

[…] [S16]. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catholic_Church_and_slavery and https://georgetownvoice.com/2007/02/08/the-jesuits-slaves/. […]

[…] https://georgetownvoice.com/2007/02/08/the-jesuits-slaves/ […]