“It really felt like you were part of the scene and that it was important to be there. And it was exciting to be there. You felt really alive when you were there.”

Jenny Toomey (COL ‘90) rode her bike from the front gates to D.C. Space in downtown Washington every night during the first week of her freshman year at Georgetown. A native of the D.C. metro area, Toomey biked to see the band 9353, which was headlining a week of concerts with other bands at the venue.

The sentiments she expressed about that week of shows were not unusual to the sentiments almost all Hoyas felt who were also members of D.C.’s hardcore scene in the mid to late 1980s.

During the ‘80s, Washington D.C. became a hotbed for hardcore punk music. At the time, the scene stayed mostly underground. Although it grew in its later years, it always kept its identity as a small scene for Washington natives. Made up mainly of D.C. natives in junior high and high school, the movement consisted of only under a hundred kids during its early years.

Just a few blocks away from the scene’s main venues, however, students on Georgetown’s campus remained, for the most part, blissfully ignorant to the creation of this grassroots community. Although a few musicians in the scene attended Georgetown, the legacy of D.C. punk remains largely forgotten for Hoyas, despite its profound cultural impact on residents of Washington.

In the basement of Copley Hall operating on the lower part of the FM band, Georgetown’s radio station WGTB featured free-form music programming, and an open space for radical thoughts and ideas to be heard publicly. For many teenagers in D.C. at the time, WGTB provided an outlet for new music, notably punk rock. In 1979, when then-university president Fr. Timothy Healy shut down the station and sold its broadcast license, even more fuel was added to the growing fire of punk rock in the District.

“Ironically, the thing that really brought WGTB to my attention was the fact that it was being closed down,” said Ian MacKaye, a punk rock artist. “[My friends from Wilson High School] were really upset about it. So when the radio station was shut down, there was a march, like a protest, right in front of Healy Hall. And I think we skipped school and went down to the protest.”

A few days after WGTB’s closing, members of the station held a benefit show at the Hall of Nations, housed in Walsh on 36th Street. The Cramps, a band part of New York’s early punk scene, headlined the show, and hundreds of teenagers from Washington attended in support of WGTB. MacKaye remembers that the night seemed almost out of control. The concert was visceral and scary, yet for MacKaye, it was also a “game changer.”

“The people there were very extreme in many different ways. They seemed to me to be sort of deviants of society,” MacKaye said. “And that was something that I felt. I wasn’t just attracted to it. I felt like I was a deviant.” Even though MacKaye said what he and the others at the show were deviating from may have differed, the fact that they were all deviating together connected them.

Raised just north of Georgetown in Glover Park, MacKaye became more interested in punk rock after the Hall of Nations Concert. He would soon become a founding member of The Teen Idles, and along with friend and bandmate, Jeff Nelson, create Dischord Records in 1980 in order to release a Teen Idles’ EP. Even though The Teen Idles broke up soon after, the D.C. punk scene was well underway.

Despite the formative Hall of Nations show, most the music venues hosting the punk scene were farther from Georgetown. The 9:30 Club, originally on 930 F Street, and D.C. Space, originally on 7th and E Street, were two of the most prominent venues to showcase punk music. While this area today has seen increased prosperity due to urban planning and the construction of the Verizon Center–the original location of D.C. Space is now a Starbucks– these clubs were once in a lesser developed section of Washington.

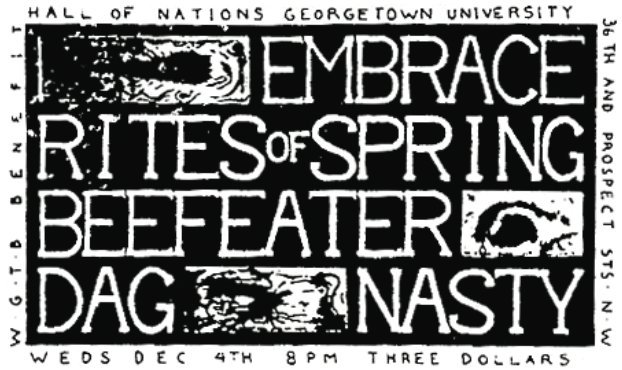

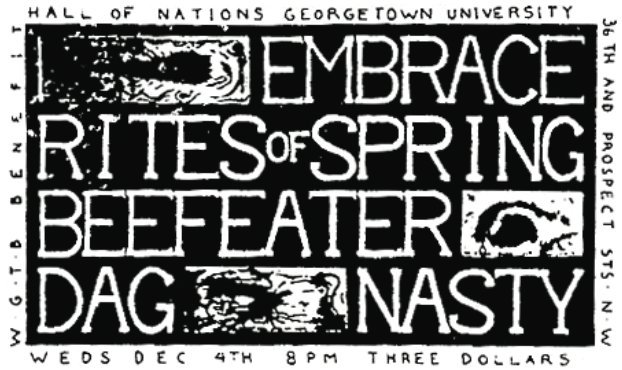

A poster promoting the 1985 Hall of Nations Concert in Walsh.

According to Professor Benjamin Harbert, who teaches a course in rock history, the move of Americans to the suburbs in the 1950s and 1960s left downtowns as empty and blank spaces, ones that punks often could explore. Given that the D.C. scene consisted primarily of kids from Washington, the curiosity to venture to these nearby, open, yet sometimes dangerous, spaces could have been reasons for the popularity of these venues with the punks.

“If you went to a show at some places, your car was guaranteed to be broken into, or you got beat up on the street or something like that,” Harbert said. “And there’s a certain thrill to that. There’s a certain excitement, especially when people of a certain privilege have the opportunity to go and do that. And you can romanticize that.”

Additionally, in a time when consumerism fueled the economy in a more commercialized world, the blight of downtown could have seemed more real to those in the scene, according to Harbert. Yet the punks kept ties to the Georgetown area as a place both to work and to hangout with friends.

“Georgetown was the neighborhood where there were places where teens could work,” said James Schneider, a D.C. native and filmmaker currently working on a documentary about the punk scene. “That’s where the record stores were. That’s where the movie theaters were … It basically was this concentrated neighborhood where they could all find jobs and be near their other friends.”

MacKaye worked at both Häagen-Dazs and the Georgetown Theatre. He remembers the liveliness of the neighborhood on Friday and Saturday nights, with kids from the area lining the streets with their cars. In the afternoons, the neighborhood was a calmer hangout with restaurants, punk outfitters, and record stores.

“Mostly, it was just a place to congregate because that’s what people did. There was no other way. It would be one thing if you wanted to call a friend, but you’re not going to run into five friends [with a telephone call],” MacKaye said. “So that’s the hang. If you want to see people, you get out of school and go to Georgetown.”

All at the same time, though, MacKaye and friends were playing in shows and running their own record label to release their music. Yet the scene remained small and mostly underground in its formations.

As punk grew in the States, more and more scenes sprouted. David Grubbs (COL ‘89) had formed bands with his friends in Louisville, KY since his early teenage years before coming to Georgetown. Already signed to Homestead Records with his band Squirrel Bait, Grubbs came to Washington in part because of the music scene.

Similar to Toomey’s leaving campus within the first week for punk concerts, Grubbs made the trip to the 9:30 Club to see the Bad Brains. He brought a group of friends from his freshman floor to the show, but noted the apprehension some had in traveling to that part of the city at the time.

Kim Coletta (COL ‘88) also chose to come to Georgetown because of the presence of the music scene. When coming to school, she realized the presence of punk on campus was much smaller than other places in the city.

“In a place like Georgetown, which struck me as pretty conservative generally speaking, you just end up finding like minded people. They kind of stick out like sore thumbs at Georgetown,” Coletta said.

Coletta would later go on to form the band Jawbox after graduating. In her time at Georgetown, similar to the other Hoyas in the scene, she made many of friendship with non-Georgetown students in the punk scene. As a result, life at Georgetown and life in the music scene became very separate for Coletta. The bassist explained how she would compress her school schedule to take up only a few days, then spend the rest of the week in the city at shows or with punk friends.

“I didn’t give a shit about what was happening at Georgetown. I cared a lot about my professors, and had some great professors. And it was a great degree, and I’m proud of my work there, and I did really well. But clubs, student groups – you know I didn’t do any of that because I was enamored with the D.C. music scene. Anything I was doing, I was doing outside,” Coletta said.

Grubbs described his freshman year as a sort of “dual life” between going to class and going to punk shows. After his hometown band Squirrel Bait broke up due to the members being separated in college, he met Dan Treado (COL ‘88) and formed the group Bastro.

Treado, whose father was a professor at Georgetown and who was raised in Silver Spring, joined the scene in his teenage years like other D.C. natives such as MacKaye and Toomey. Once coming to Georgetown, Treado noted a clear divide between kids in the punk scene and students on the Hilltop.

In 1985, Treado hosted another benefit concert for WGTB at the Hall of Nations, and prominent D.C. bands Embrace, Dag Nasty, Beefeater, and Rites of Spring all played. Although Treado tried to convince his friends from school to come, only punk kids from the District made up the audience mostly.

“The scene kids who went to shows showed up, and the Georgetown students did not. It’s kind of funny,” Treado said. “There was kind of a demarcation line, and the typical Georgetown kid didn’t cross it. It was unfortunate.”

According to Treado, Grubbs, Coletta, and Toomey, the kids that were both students and in the scene in general formed a small, tight-knit group that held a small presence within the larger D.C. music community.

“There were handful of us, and we found each other,” Toomey said.

For MacKaye, Georgetown University and the punk scene remained entirely unrelated. While he and many of the D.C. natives welcomed the few Georgetown students who were punk musicians into the scene, the institution and general student body did not engage at all with punk.

“At the time, [the scene] was not real to them,” MacKaye said. “But the thing was, we didn’t need their validation. We could give a f*ck about them. So it didn’t matter whether or not any of these universities paid any attention to us.”

While not explicit promoting political messages, the punk scene often tended to attract a more liberal-minded crowd, as seen in the various benefit shows for economic justice and against South African apartheid.

For the punks at Georgetown, many expressed a feeling of separation from the general student body that they claimed to be much more conservative at the time.

“I had never been around so many extremely conservative people my own age,” Grubbs said. Additionally, he noted that punk was not even on the radar of the average Georgetown student at the time. Toomey echoed similar sentiments, saying, “[Being in the punk scene] wasn’t seen as cool … I mean what was seen as cool in some of the classes I was in was money.”

As a result, many of the political activities that the punks engaged in throughout Washington added to the dual life that Georgetown punks lived. Both Coletta and Treado took part in hanging posters around the city with the words “Meese Is a Pig” to show opposition to former attorney general Edwin Meese.

[pullquote]“In a place like Georgetown, which struck me as pretty conservative generally speaking, you just end up finding like minded people. They kind of stick out like sore thumbs at Georgetown.”[/pullquote]

According to Harbert, a lot of the activist tendencies in the scene came as a result of many D.C. punks’ upbringings.

“Their families were professionals, but were people who were committed to certain issues of social justice. They’d have activists come and stay with them, ” said Harbert.

For Toomey, activism took the form of engagement with the group Positive Force. Associated heavily with the punk scene, Positive Force is an activist group that continues to seek social change and youth empowerment. Grubbs engaged in punk’s activist culture through a program at Georgetown in which he volunteered as a tutor in prisons for two years. Despite the noticeable conservatism on campus, Grubbs still praised the unique culture of engaging with volunteer work while at Georgetown.

“You cringe when you hear this, when kids say, ‘punk rock changed my life,’ but it was a really formative thing,” Treado said. “I wouldn’t have had it any other way.”

Though no longer actively performing in the punk scene, Treado still lives in D.C. and works as a visual artist. For many of the other punks, the District remains home as well despite bands either breaking up or taking an hiatus. Their work in the music scene also remains in the D.C. area.

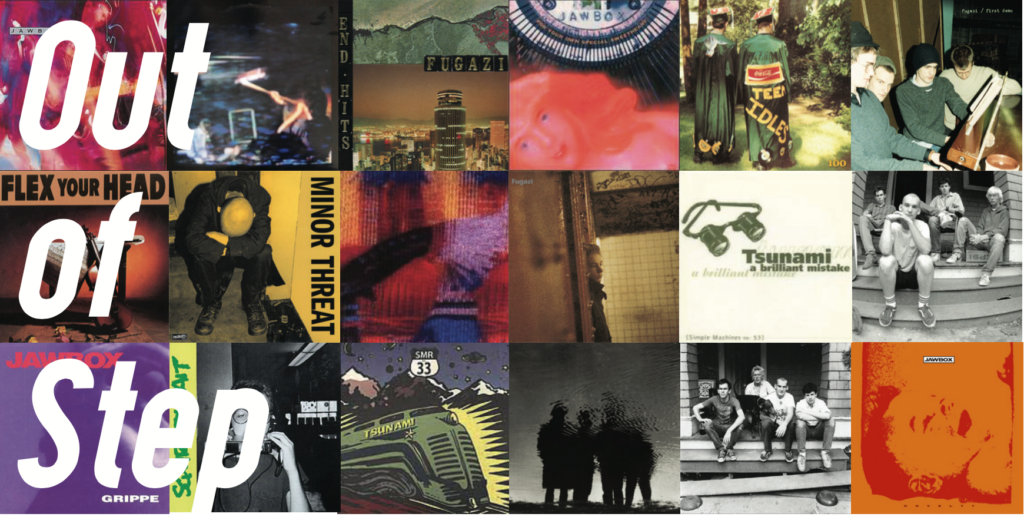

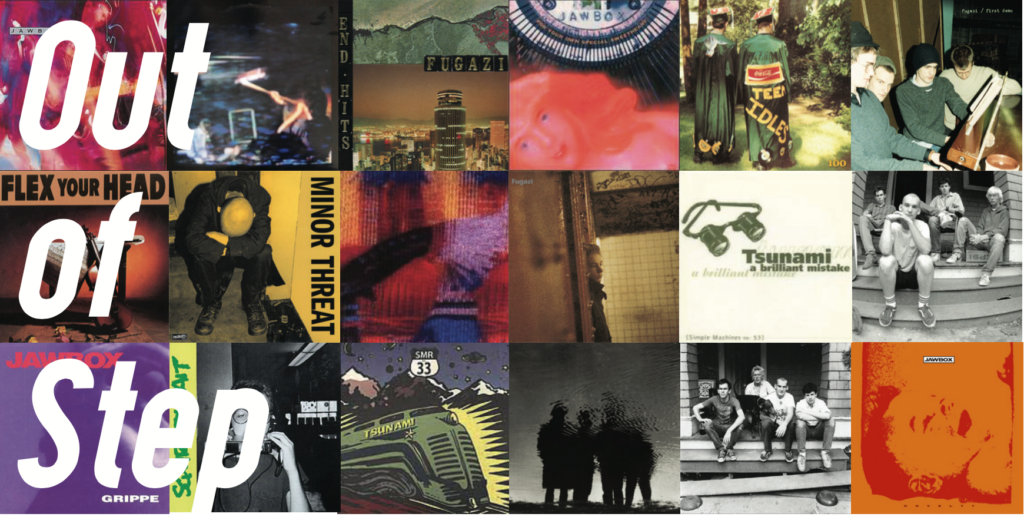

MacKaye still runs Dischord Records and manages the label’s massive back catalog. Coletta, who previously worked at Dischord, also manages the catalog of bands from her own label, DeSoto Records, which she formed to release a Jawbox record in conjunction with Dischord.

“There’s such a vibrant community of musicians who are still doing things that matter at an age that nobody thought you’d be involved in something related to punk rock,” Harbert said. “When the people who started this, when they were teenagers, and they didn’t start it to do this, but the people who started making music that was local and having control over it, what they did is, and they didn’t even realize, they sowed the seeds for having something that was sustainable.”

Despite largely missing out on contributing to the scene and being very separated physically, Georgetown and D.C. punk may not have been as disconnected as it appeared at the time, according to Coletta.

“I think the D.C. music scene is a thinking person’s music scene. It always has been … D.C. was just more thoughtful [than other music scenes.] And I feel like Georgetown was thoughtful,” Coletta said. “I found Georgetown students, even though very different from myself, pretty smart and thoughtful. And I found D.C. music scene people smart and thoughtful.”

Slight correction: Ian worked at the Georgetown Theater, not the Key. Or did when I was at Key ca. 1980. (Great article, BTW.)

Great article and those were great times – SFS ’88

[…] sessions recorded 1977-78 at Track, plus a live set hosted by John Hall at Georgetown’s radical radio station, WGTB — released in 1982 (Adelphi 2-LP AD […]

I is remember go to 930 Club and see all them cool punk band. For me it is real sad and I miss. All them there good like shops is be go. Even Smash’s be gone. Such shame. I is lost when me return home to DC. It be strange feel. Me grow up now. So disappoint.