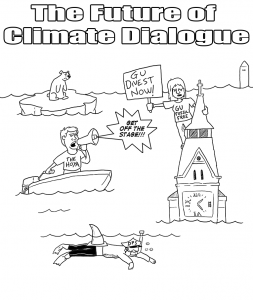

As representatives from over 180 countries, intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations and the media fly to Bali, Indonesia for the thirteenth United Nations Climate Change Conference, they prepare for two weeks of what has been perceived as “make-or-break” negotiations on the future of international climate change policy.

The expiration of the Kyoto Protocol emissions reduction commitments for developed countries in 2012 is the priority for the December 3-14 summit . The meeting will focus its attention on the emerging economies of India and China, heavy contributors of atmospheric greenhouse gases but nonetheless considered developing countries.

The United States, the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases and the only large developed nation still opposed to mandatory emissions reductions (Australia’s incoming prime minister, Kevin Rudd, ran on the platform that his country will ratify the Kyoto Protocol), will share the spotlight with China and India. The mitigation of potentially irreversible effects of climate change lies in the hands of large, energy-intensive economies.

However, a look beyond the luxury hotel on the Indonesian island hosting the summit should remind the delegates of the urgency needed for adaptation measures to protect vulnerable developing countries. Localities need to adopt early warning systems, evacuation plans and building shelters to cope with extreme weather events. Adaptation, which focuses on adjustments in the natural or social systems as a response to climate change, has remained in the backdrop in past policy debates.

The United Nations Human Development Report released just last week predicted that developed nations will need to provide $80 billion annually by 2015 to increase vulnerable countries’ capacity to alleviate climate-related risks. So far, adaptation efforts have been met with disappointment. According to the Development Report, only $26 million has come through for the climate-adaptation assistance program under the UN.

Nevertheless, international development agencies have been incorporating climate change risks into their development plans. The World Bank, for example, conducted technical analysis of risk management and pioneered insurance work in the Caribbean, Latin America and South Asia.

Temperature increase, sea-level rise, precipitation, extreme-weather events and biodiversity loss will be unevenly distributed throughout the world and across different sectors. Therefore, as uncertainty about climate change impact pervades political and scientific communities, local assessment is an indispensable part of sound adaptation measures. Adaptation to climate change not only creates a buffer against future dangers, both natural and human-induced, but also takes international climate policy to the local and human level. Thus, as leaders debate the science, economics and political viability of a mandatory emissions reduction timetable, they can no longer ignore the equal importance of taking immediate, effective action against the existing and eminent threats to the livelihood of millions.

The future leaders from Georgetown should keep this in mind as well, as their careers are likely to cross paths with one of the most dynamic problems the international community has ever faced. It will hinder sustainable development plans by putting further stress on diminishing resources in vulnerable areas in rich and poor countries alike. It will change business strategies and spur new business opportunities. New and growing vectors for diseases will pose a tough challenge for medical professionals.

Many students feel that future participation is not enough and, fortunately, groups like Eco-Action and Campus Climate Challenge have recognized the importance of immediate action. I hope those groups on campus that have decided to become part of the solution will include fundraising and awareness for adaptation needs in their increasingly successful and visible campaigns around the University.