A bomb went off in a shopping center, killing one and injuring 38. Within twenty minutes, ambulance sirens whizzed down my street with victims in tow. A young boy in nearby Gaza distributed sweets to passersby in celebration of the attack.

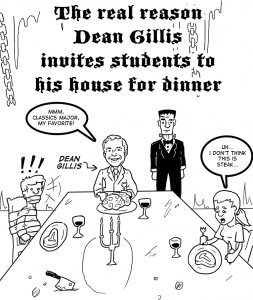

Spending time in the hotbed of religious conflict that is the Middle East, I came to know an ugly picture of the role religion plays in society today. In some cases, it is a weapon. As a tool of propaganda, religion becomes a method to rally up the masses to turn political wars into religious ones. How does religion attract people to fight a war? Well, with a hot meal to start.

The poverty-stricken masses of Cairo are fed-up with an oppressive government that doesn’t care, a supposedly “grand America” that supports this negligent regime, and a city that doesn’t offer so much as clean air. “Religious” leaders seeking power use the compelling context of Islam to attract these people and to convert them into devotees. These figures augment their status in relation to the government and obtain a personal following. They promise a sanitized political system and a chance for people to have greater ownership over their own lives. Social services, like the hot meal that government welfare rarely provides, entice the average person to keep coming for more.

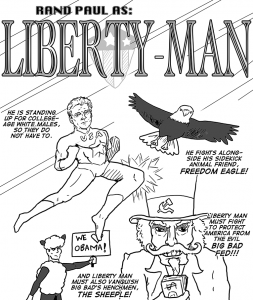

In addition to religious fervor, people are turning against the West for ideological and political reasons. There is resentment against the fallen status of the Middle East since the great days of the Islamic empire. Places like McDonald’s that represent globalization take the brunt of societal frustration and jealousy that result from hurt pride and poor economic status. Last September 11th, as I used the free wireless internet at a Cairo McDonald’s not a far walk from where Mohammad Atta grew up, I began to think about how the restaurant, as a symbol of America, could be a target for a terrorist attack. Committing murder over a hamburger; this is how far religious fundamentalism has gone.

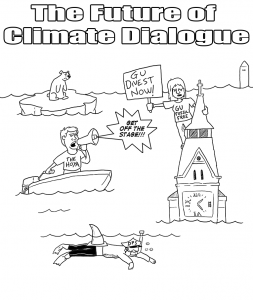

As much as conflict in the Middle East is about power and religion, it is also about identity. Every Israeli is conscripted to military service at age 18, but they are certainly not all fighting on behalf of religious beliefs. Of the Israeli population, 40 percent are avowedly secular. Walking the streets of Tel Aviv, it’s easy to find a café that serves pancetta or shrimp—there’s a market for these non-kosher foods. If they’re not all fighting for their biblical right to the land, why are they fighting? Israelis fight to protect their right to maintain their way of life in a country they fought dearly to obtain. Checking people for bombs at every mall, restaurant, and club—it’s for the sake of security of identity.

Judaism’s position in Israel is very different than that of Islam in Arab society on most, but not all levels. Maybe there is something in common between a man and his boyfriend (both of whom served in the army because they’re Israeli citizens, and Israel is one of the few countries that allows soldiers to be openly homosexual) at the beach in Tel Aviv enjoying a shrimp cocktail on the Sabbath, and men smuggling weapons into Gaza for their holy war against Western liberalism. People on both sides, religious or not, are struggling to establish a concrete identity.

Is something as nebulous and intangible as an identity worth sacrificing the best years of your youth to army service, or even your life, to protect? While in Poland this past April, I visited several concentration camps. At Majdanek, where nearly every structure from the gas chamber to the barracks still stands, there is also an enormous pit. Inside are the ashes, several tons, of some of the 79,000 who were murdered there. Standing at the edge of this enormous pit of cremated men, women, and children—all reduced to organic matter—I realized the true seriousness of the issue of identity.