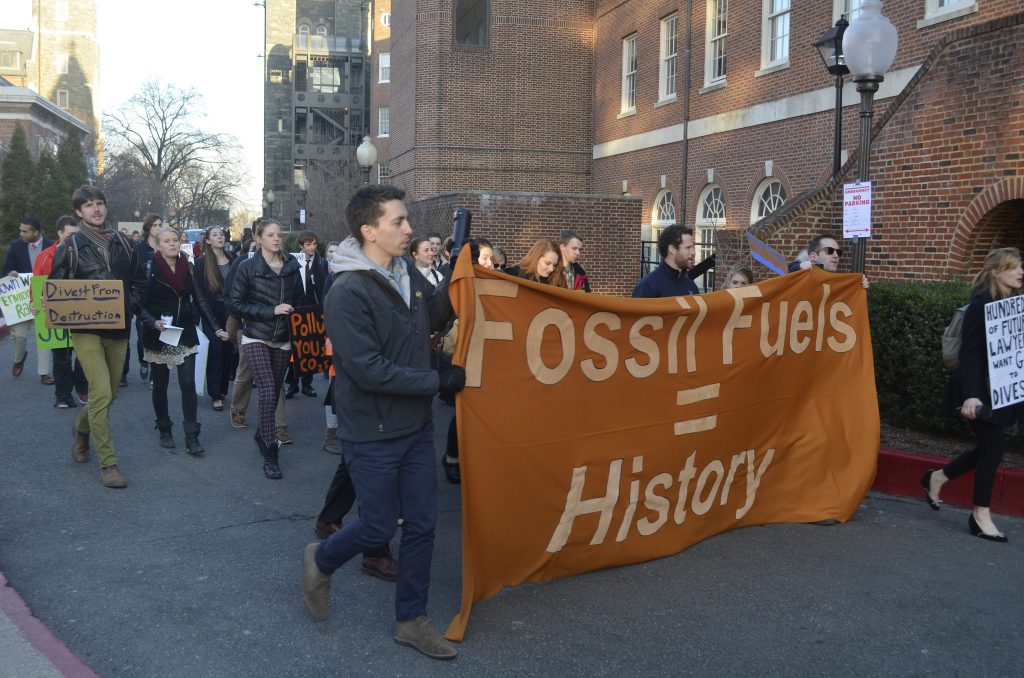

File Photo: Ambika Ahuja/Georgetown Voice

More than 30 years ago, Georgetown University activated 4,464 solar panels on the roof of Bunn Intercultural Center, constructed after the 1973 oil crisis. In 2013, the Environmental Protection Agency recognized it as a Green Power Partner of the Year. These are incredible achievements.

A fair assessment of the university’s progress and sustainability, however, must look beyond its past capital projects and ambitious sustainability goals. Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certifications and EPA recognition does not necessarily mean that this campus is truly as green as it can be.

For example, Georgetown says that its greenhouse emissions in metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2013 were 69.9 percent lower compared to those in 2006. One of the ways it did so was to purchase renewable energy certificates (REC), which provide funding for owners of renewable power sources that create electricity for the grid. The RECs, however, allow it to claim additional credit for the environmental benefits of the renewable power sources in which it invested. Without including RECs in its calculations, the university only reduced its greenhouse emissions by 19.4 percent.

In a similar dilemma, the University of Pennsylvania has bought more RECs than any other participating institution in the EPA challenge since 2009, but some students, according to the Daily Pennsylvanian, do not see the merits of this act. They say that RECs are “one-time certificates with no return on investment in the future.”

Administrators also want all future buildings and major renovations to achieve LEED Gold certification. However, its current standards amount to little more than a token achievement in today’s construction projects. In October 2012, USA TODAY analyzed 7,100 LEED-certified commercial buildings and found that, too often, building projects receive credit for providing a view of the outdoors or having a design team member pass a LEED exam.

Further limitations on Georgetown’s sustainability initiatives stem from the Office of Sustainability’s small size. Only one full-time staff member and a few student interns run the office. Bureaucracy and red tape have hampered an exciting project to build solar panels on Leo O’Donovan dining hall’s roof, as Georgetown Energy, the student organization responsible, has had to work with so many different offices in the university.

Climate change is one of the most important, if not the most important, issue of our generation, and Georgetown University has made considerable strides. However, its work is far from complete. If Georgetown truly wants to become a green campus, the Office of Sustainability must grow further, and the university needs to promote grassroots initiatives to change the habits of students and staff. Administrators, too, must take the lead on environmentally-conscious master planning and do more than simply aim for awards and certificates that provide talking points.