Fresh food isn’t exactly hard to find for Georgetown students. Each Wednesday, the Georgetown University Farmers Market sets up in Red Square, offering fresh fruits to students right in the heart of campus. A Safeway and a Whole Foods sit further up Wisconsin Avenue, but are still within a walkable distance for students, as well as easily accessible by GUTS shuttle. For those willing to venture farther from the Hilltop, Trader Joe’s is a feasible option, while Vital Vittles is the closest source of groceries on campus. And though complaining about Leo’s is a favorite pastime of Hoyas, the dining hall also provides easy access to meals. This convenience makes it easy to forget that vast disparities in food access exist across the city, where food insecurity is a continual and growing issue.

Fresh food isn’t exactly hard to find for Georgetown students. Each Wednesday, the Georgetown University Farmers Market sets up in Red Square, offering fresh fruits to students right in the heart of campus. A Safeway and a Whole Foods sit further up Wisconsin Avenue, but are still within a walkable distance for students, as well as easily accessible by GUTS shuttle. For those willing to venture farther from the Hilltop, Trader Joe’s is a feasible option, while Vital Vittles is the closest source of groceries on campus. And though complaining about Leo’s is a favorite pastime of Hoyas, the dining hall also provides easy access to meals. This convenience makes it easy to forget that vast disparities in food access exist across the city, where food insecurity is a continual and growing issue.

According to 2013 census data, 18.6 percent of D.C.’s population lives below the federal poverty line. Even more are food insecure, meaning that “at times during the year, the food intake of household members is reduced and their normal eating patterns are disrupted because the household lacks money and other resources for food,” according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. There are many issues that cause insecurity: access to purchasing food, affordability, and the high cost of living in the city all contribute to challenges in feeding households and individuals.

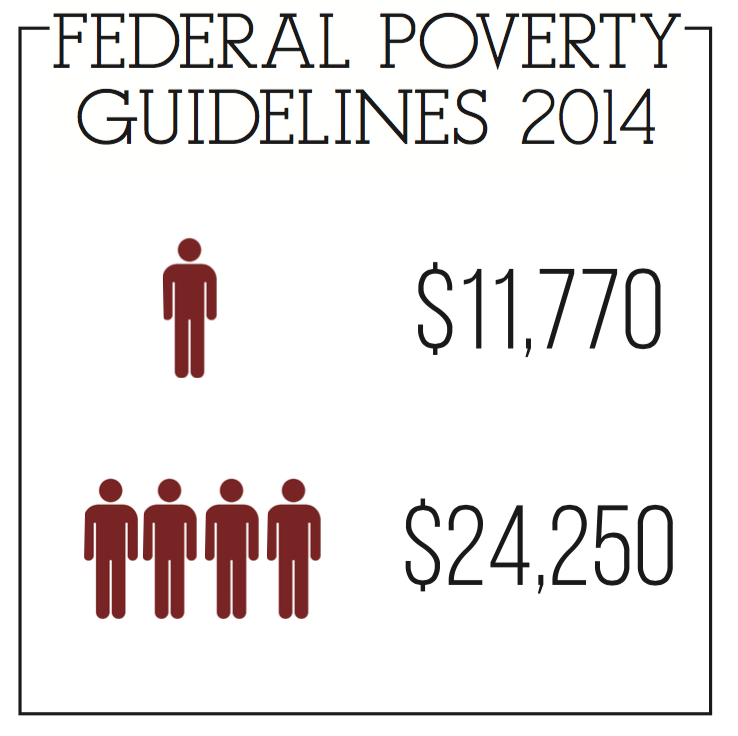

“There are approximately 700,000 people in the D.C. [Metro] area who are at risk of hunger,” said Dylan Menguy, Capital Area Food Bank’s (CAFB) spokesman. The organization, which is the largest of its kind in the area, distributes food both directly to clients and through more than 400 other organizations in D.C., Maryland, and Virginia. “[700,000] is calculated based on food insecurity,” he said, considered by CAFB to be those earning less than $21,727.80 per year for an individual, which is 180 percent of the federal poverty threshold. According to Menguy, CAFB includes those earning above the poverty level in this measure to account for the “incredibly high” cost of living.

Additionally, certain populations have seen greater increases in insecurity in recent years, further contributing to the high rate of those at risk of hunger. “Hunger is on the rise among seniors as the baby boomer generation ages,” Menguy said. The CAFB “finds that the senior population, because they’re living on a fixed income and have special needs in term of nutrition; they’re often not getting enough food.”

There’s another demographic in the city that’s overlooked in terms of food insecurity, according to Georgetown professor Dr. Marcia Chatelain, who is currently writing a book about race and fast food: young professionals.

“The incredibly high cost of living means that more people need food assistance,” she said. “It’s not just poor working families, there’s a large number of young people working in low-wage professional work because non-profit sector wages don’t keep up with the cost of living. These converge to make [food assistance] enrollment so high in D.C.,” she said, referring to the 21.97 percent of the city’s residents registered in nutritional support programs.

Food deserts and insecurity

While there are a multitude of stores within walking distance of Georgetown’s campus that sell fresh food and produce at different price points, this is not the case across the District: many areas of the city fall into the category of what USDA classifies as a food desert—an area in which fresh produce is not easily accessible due to a lack of purveyors. These areas, which are concentrated in the eastern half of the city, are not necessarily completely devoid of food access; in general, many have corner stores and smaller shops, as well as fast food and other restaurants. However, access to full-service grocery stores like the ones that Hoyas can stock up on fruits and vegetables at is limited.

Glover Park Farmers Market. Photo: Daniel Varghese/Georgetown Voice

In these areas, one of the primary issues leading to food insecurity is a lack of meaningful access—the practical ability of residents to get to and afford fresh food. Living more than a mile from a grocery store, or a half mile without having access to car, are the qualifications for a food desert according to USDA. It’s easily clear where these deserts are located in the city: of the 45 full-service grocery stores, only two are located in Ward 8, the most southeastern region, compared to eleven in Ward 3, which makes up the areas north and west of campus. Not coincidentally, Ward 3 is one of the city’s most affluent areas, with a poverty rate of 8.2 percent, compared to 37 percent in Ward 8 as of 2012.

Factor in the city’s high cost of living, which increases households’ other expenses, and this all adds up to one of the nation’s highest rates of enrollment in nutritional aid programs, which aim to combat this high rate of food insecurity.

Federal funds and programs

The most well known program is the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps. Residents whose income is up to 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Guidelines are potentially eligible for this program, depending on the size of their household and other expenses, according to the D.C. Department of Human Services. These residents who enroll receive an EBT (electronic benefit transfer) card loaded with a certain amount of money each month.

Those benefits amount to a maximum of about $4.87 per day, per person, though the exact allocation is determined by a combination of these factors. To put that number into context, a Hoya with a 14-meals-per-week plan pays about $10.05 per meal at Leo’s. The SNAP program is intended to complement residents’ income, and to increase their ability to purchase food; however, given the city’s cost of living, it often falls short of allowing residents to buy more expensive items, such as fresh produce, even when there is access.

This program has been relatively successful in eliminating the gap in daily caloric intake between those and who are and are not enrolled, according to a recent review of nutritional studies in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine. Overall, the diets of Americans who do and don’t participate in SNAP are fairly similar in the number of calories eaten per day. However, a significant gap remains between those who are and are not enrolled one particular and important category: diet quality. Participants in the program consumed fewer fresh fruits and vegetables, contributing to a lower quality diet in terms of nutrition.

Other benefit programs target various specific populations in need of sustenance support, including the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which provides short-term assistance to those qualified by the DHS as earning “low or very low income, and [who are] either under-employed (working for very low wages), unemployed or about to become unemployed.” Senior citizens can be eligible for programs such as the Commodity Supplemental Food Program and the Senior Farmers Market Program, often referred to as senior checks, both of which aim to improve the nutrition of elderly residents.

“I don’t think the average American knows any kind of details about those programs, and how they’re administered,” said Georgetown professor Dr. Leticia Bode, who teaches a course on Food Politics in the Culture, Communications and Technology program. “They’re broadly construed as welfare, and starting in the 1980s, as a nation we have [had] a poor perception of welfare.”

Despite this, there are a multitude of programs on the local and federal levels working to address these unmet needs, as well as organizations approaching the issue in the nonprofit sector.

Despite this, there are a multitude of programs on the local and federal levels working to address these unmet needs, as well as organizations approaching the issue in the nonprofit sector.

Making markets affordable

Many of these programs that target increasing produce consumption are run through the many farmers markets operated throughout the city. Initiatives such as Produce Plus and the Matching Dollars Program, as well as the acceptance of federal benefits at these markets, aim to contribute to closing the gap in access to fresh produce and help stretch tight budgets farther to support healthy eating.

Markets at 51 different locations in the city accept SNAP, WIC, and Senior benefits, though as Nick Stavely, Market Manager for Community Foodworks, said, “the benefits are market-specific,” meaning that for those without a local market offering these programs, there is an additional barrier in finding and accessing others.

At the participating markets, “individual vendors can’t accept EBT cards,” said Meghan McGonigle, who has worked with the organization D.C. Greens at the USDA Farmer’s Market. Instead, cards are swiped at the markets’ information tents in exchange for tokens. These tokens “can be used for fruits, vegetables, bread, eggs, cheese, and meat, but nothing that’s prepared,” McGonigle said.

Those tokens are then able to redeemed as if they were cash at many of the stands selling produce, although the selection and prices vary across markets. At certain markets, including the Community Foodworks markets in Columbia Heights and Brookland, these benefits can be doubled through a matching program, allowing residents to receive twice as many tokens or vouchers as they redeem.

Produce Plus, a city-wide initiative that the Department of Health started last June, also aims to help alleviate barriers to fresh food. The program offers ten dollars in checks per household to residents who demonstrate enrollment in SNAP, WIC, TANF, Medicaid or Social Security, which can be spent at forty participating markets.

Produce at Glover Park Farmers Market. Photo: Daniel Varghese/Georgetown Voice

“[Produce Plus] is one [program] where there’s more people making a longer trip to find the checks, and that’s due to the fact that there’s no cost to use the checks,” Stavely said, as residents don’t need to spend any of their benefits to receive the checks, unlike the doubling programs.

“About one-fourth to one-third of customers are on benefits [at the Historic Brookland Farmers Market]”, he said, which is in its second year. This varies from market to market – James Little of Kuhn Orchards estimates that only a dozen of his customers at the Glover Park Burleith Farmers Market use the Produce Plus checks. “It’s not a lot of people that use it,” said Westmoreland Produce’s Anjelica Medina, who sells alongside Little at the weekly market on 35th Street.

While residents have benefitted from the Produce Plus program over the summer, as well as from their ability to redeem benefits at Farmers Markets in addition to grocery stores, issues arise as the seasons begin to change. Produce Plus will end for the year on Sept. 30, and while Farmers Markets shut down for the season at varying times, the majority are closed for a period of several months, throughout the fall and winter.

“We hear from people that they want Produce Plus to continue,” Stavely said, whose market is among those that will close for the season from mid-December through April.

Uprooting barriers to access

In addition to the organizations and programs working to increase produce sales throughout the city, there are a multitude of groups approaching alleviating food insecurity by changing the methods of production from the ground up.

Urban agriculture has gained ground in D.C. over the last decade, aiming to shorten the distance between producers and consumers within the city.

“The area we’re in … is a food desert, so the closest grocery store is a Giant about a mile and a half away,” said Melissa Miller, farm manager at Common Good City Farm, which occupies half an acre on V Street NW. They grow more than 5,000 pounds of food each year on the lot of a former elementary school.

“They just built a Whole Foods, actually, or they’re building it, about a quarter of a mile away, but that still doesn’t provide food access to people who are on a low socioeconomic scale; that’s not too affordable,” Miller said. To meet that need for affordable and convenient produce, the farm offers community-supported agriculture, with full-price and income-qualifying memberships for community members who join and receive a bag of fresh produce each week.

“Some people pay as little as $10 each week” for their weekly produce, Miller said, as well as attending workshops and educational programs, and purchasing individual items at weekly markets, where benefits programs are accepted.

Elsewhere in the city, urban farming and community gardens likewise offer a shorter distance between the producers and consumers.

[pullquote]“There’s not a food bank in the country that will say that need has decreased in any way. Hunger is on the rise, wages haven’t kept up with inflation, food prices have gone up, housing, shelter, clothing, those are expensive.”[/pullquote]

Unlike urban farming, which focuses on producing large quantities for large populations of recipients, community gardens provide plots for individuals and households to plant and maintain individually. There are 26 community gardens under the jurisdiction of D.C.’s Department of Parks and Recreation, most of which are currently full and have waiting lists for plots to open up.

At Bruce Monroe Community Garden, located near the Columbia Heights Metro station, about 100-150 people rent plots and are members, according to Gabby Cosel, a volunteer. “Those folks use shared plots too, and help plant to maintain them. There’s a larger community in the neighborhood that can come to the garden. Our garden is in the public park so it’s open … and anyone in the community is welcome to pick from the shared beds and plant them too, if they want to,” she said.

Education also plays a substantial role in the success of these gardens, as well as in markets, when it comes to increasing produce consumption.

“If you put a community garden in an underserved community, and you’re not really connecting with the community, and you suddenly start producing all this produce and selling it at a farmer’s market at subsidized rates, so it’s available, it’s affordable, it’s accessible, people are still not going to buy it because they don’t know how to use it and they’re not used to it,” said Jessika Brenin (NHS ‘17), a resident of Magis Row house, Rooted: Social Sustainable Service, which focuses on multi-faceted issues of food. “So it’s about education.”

Chatelain echoed this, citing the University of D.C.’s Muirkirk Research Farm as an example of urban agriculture that targets its surrounding community, by growing “specialty and ethnic crops,” including “many herbs and spices from Ethiopia and several species of vegetables from West Africa,” according to their website.

“They grow food that’s specific to ethnic groups in the city,” Chatelain said, “so it’s food that’s familiar,” a key component of making this produce accessible within the community.

Markets on the move

The distribution model has also started to undergo changes in response to food inequity, including by those who are looking to overcome the lack of traditional stores in food deserts by operating mobile food markets instead, that bring produce into areas with limited access.

“The real problem lies in the delivery of the food, [not] the production of food,” said Surabhi Agrawal (MBA ‘16), co-founder of Farm Fresh Trucks, a startup that won the Georgetown Entrepreneurship Initiative’s Entrepalooza competition in April 2015. Agrawal and her co-founder, Areebah Ajani (CCT ‘15), believe the solution is in bringing food to consumers, rather than consumers traveling to them, and hope to launch a mobile Farmers Market truck in D.C.

“We decided that the Farm Fresh Truck model was going to be most effective, because the thing is that these larger chains are not going into these markets,” Agrawal said. “One of our goals was to figure out how to be a place that could deliver food, and provide fresh access … it’s like a food truck, but a farmers market version, where you can come and get your produce and things like that.” She and Ajani are continuing market testing and pursuing community partnerships as they work toward launching their mobile market truck.

Organizations such as Martha’s Table, which is based out of the U Street neighborhood, also incorporate this method of bringing produce directly to consumers, offering markets at local elementary schools throughout underserved areas, as well as running trucks that bring nutritious meals directly to those in need.

“Just because you come from a struggling family or situation, you should have the same access to choices as those from different situations,” said Natasha Khanna, Assistant Director of Communications for Martha’s Table.

Calling for change

As the city continues to change economically, there are subsequent changes in certain needs—gentrification and economic changes in neighborhoods have caused a realignment of programs in some cases, as well as changed the exact nature of food deserts, such as the area now home to Whole Foods in Ledroit Park. These changes keep organizations constantly adapting, looking to find new models of improving food security on both the federal and local level.

“There’s not a food bank in the country that will say that need has decreased in any way. Hunger is on the rise, wages haven’t kept up with inflation, food prices have gone up, housing, shelter, clothing, those are expensive,” Menguy said. Whether groups are growing or distributing produce, or working in other roles such as improving education and affordability, it all boils down to a solution that’s already been reached, Menguy said.

“We know the answer, food provides hunger relief,” he said.

The issue that remains is accessing it.

Good article, but no mention of Arcadia’s mobile markets?