Erin Annick

For a Friday night, it was a pretty mild party. For one thing, the only music was coming from my iPhone; for another, all the guests were seated around my kitchen table. But the knock on the door came all the same.

The Student-Neighborhood Assistance Program (SNAP) has a reputation that precedes it far before you hear them knock on your door. They’re the bad guys, the embodiment of neighbors who resent our very presence, and a larger symbol of the added stipulations placed on students living off campus. To be fair, most of the adjustments to off-campus life are adjustments to the real world that the university has little to do with. Last year, living in an on-campus townhouse, I had to take out my own trash, or my trash wouldn’t get taken out. This year, living in a townhouse off campus, I have to take out my own trash, or I’ll be arrested. Considering I probably should have been arrested for the things I did in Blue House—which I am legally forbidden from commenting on by an injunction from the Supreme Court of New Zealand—this change is stark and unforgiving.

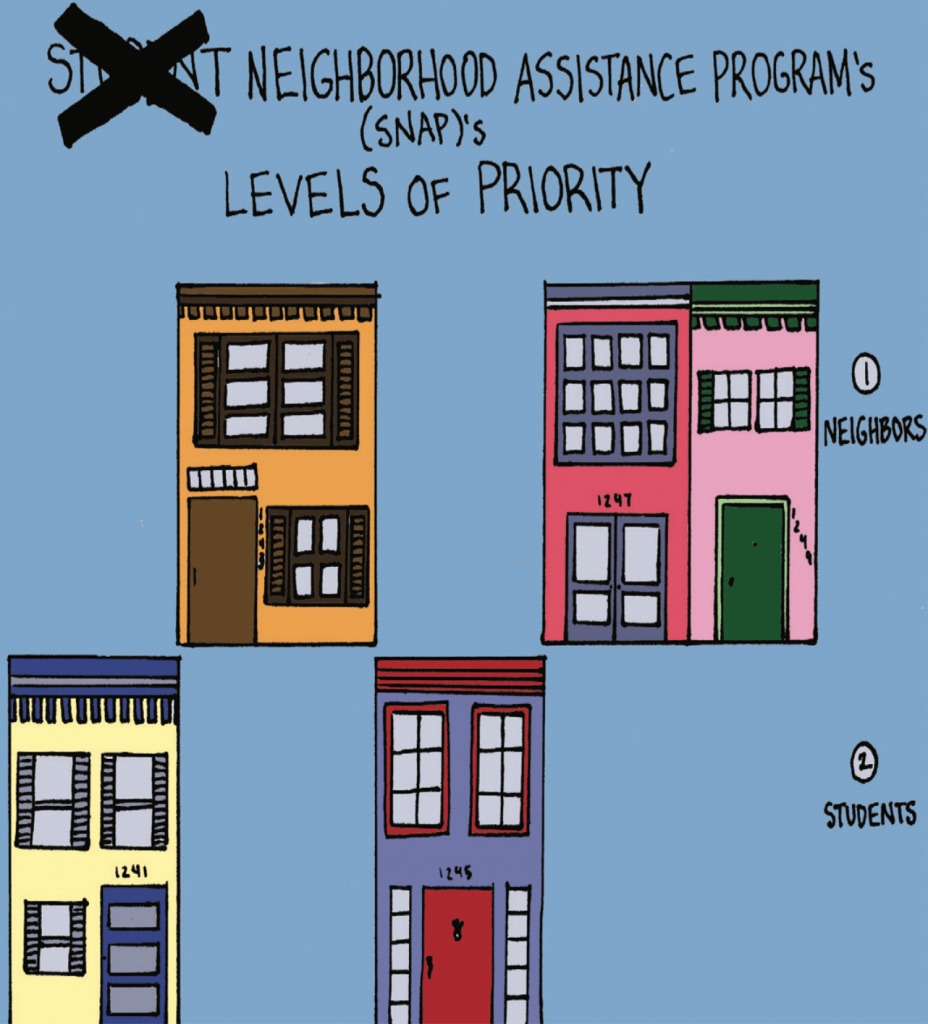

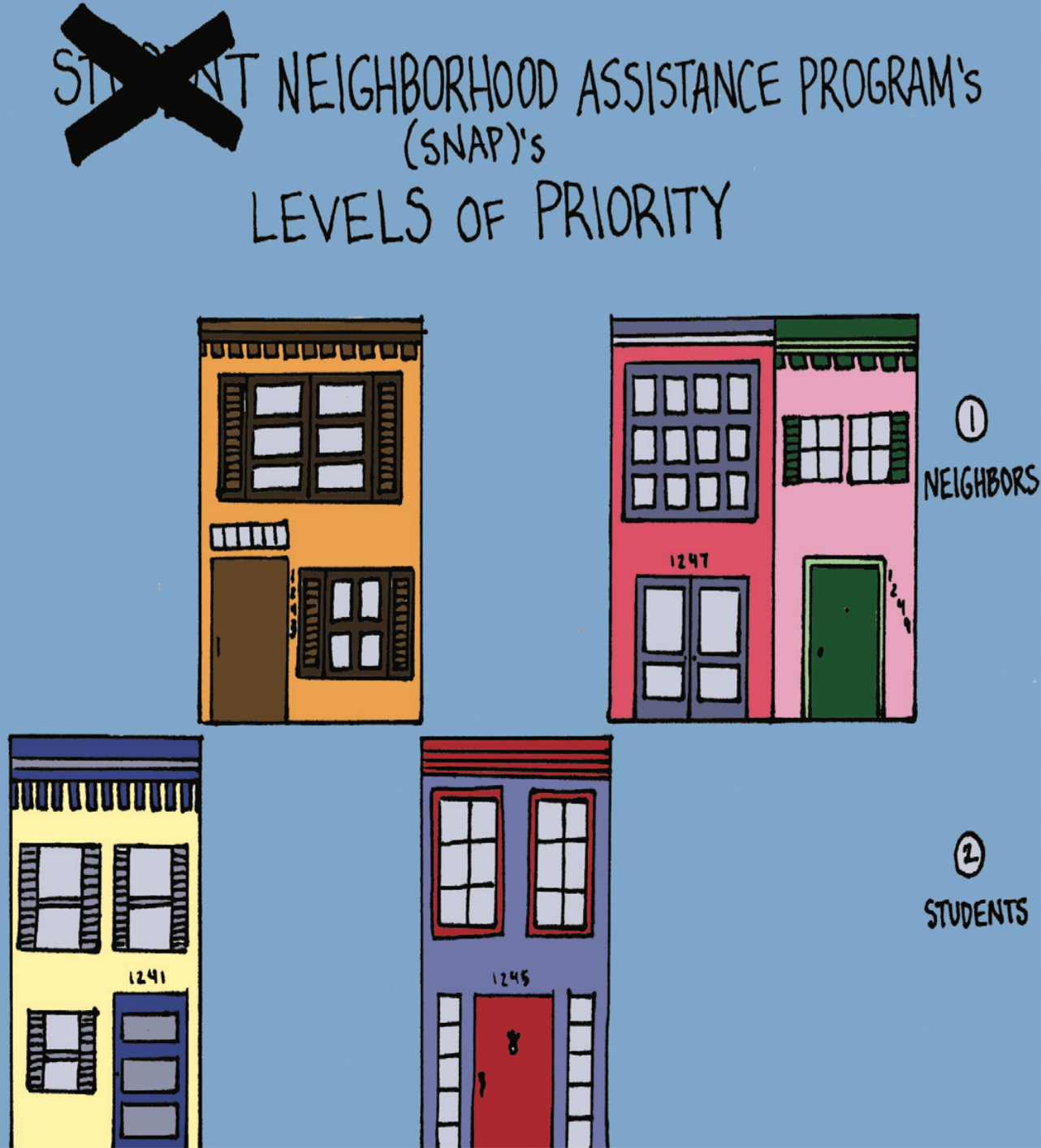

SNAP, as mentioned before, is a good symbol of the existence off-campus seniors have with their community. They may have a villainous reputation, but most of their off-campus knocks aren’t write-ups, but well-intended warnings to students who are rowdy. I learned this while talking to the Office of Neighborhood Life as I investigated what had happened as a result of the knock on my own door. But that wasn’t how it felt in the moment, when a university official was addressing me in my own home telling me to turn down my music and that he was going to file a report about the incident. What did that mean? Was I being written up? Was off-campus life so restrictive that six people listening to unamplified music was enough to get written up? Fortunately, it was not, but it was enough to make me realize that I was a special subclass of resident.

Double trash violations are a good example of how the university treats seniors like children. If off-campus seniors get cited by the city for leaving bins out or taking trash out improperly, they also get cited by the university, for which the punishment is community service. When I checked into the Office of Neighborhood Life for my meeting, every other check-in besides mine was for trash violations. This is patently ridiculous; any other resident of the neighborhood would only pay the fine from the city. To have the university running around checking on students seems micro-managerial and overbearing.

When you move off-campus, the university requires that you register your off campus address and attend an off-campus living info session. But what extra responsibilities do students who live outside of SNAP’s boundary (Burleith, West Georgetown, Foxhall and the Cloisters) have? What about those few students who live in Rosslyn? I now wonder where the imaginary line is within which the university will bother to care if you’re noisy. The university only cares about these neighborhoods because they’re the only reason things like SNAP exist: the neighborhoods hate us and they have all of the power.

Not only is this too politicky for the average student moving off-campus, they also have no say in the matter. So going forward, it’s worth looking at a few things you can do to improve your off campus life.

One of the best decisions I’ve made this year was getting to know my neighbors, a young couple with an adorable toddler. Talking to them is not only personally enjoyable, it’s also the single best thing I can do to prevent noise complaints. It also helped me put myself in their shoes; if I were them, I wouldn’t want loud college students waking up my kid either, especially not if what’s waking him or her up is a verbal storm of rather creative curses.

Living off campus has also allowed me to explore my new local area and learn about a new part of Georgetown. Up further on my part of 33rd Street are some hole-in-the-wall art galleries, and there’s an amazing Thai place that offers student discounts twice a week. Perhaps best of all, we’re right next to both Pizza Movers and Manny and Olga’s. We’re trying to befriend the perpetually-drunk workers so they’ll just let us cut through their back alley to save time.

Prior to moving, I also bothered studying up on where my new address was in DC. Not all off-campus addresses are in the same vicinity; Houses in Burleith and West Georgetown can be 10-15 minutes away from each other. My own address is only a 10 minute walk from Dupont Circle, which has led to several Sunday mornings at the DuPont Farmers Market. What’s more, the bus routes right next to my house take me right to the south side of the circle, or up into Glover Park. Being off campus may have cost me proximity to campus, but it has allowed me to be a much more active citizen of Washington, D.C. at large.

Being an off-campus student has undeniable drawbacks. Some are inevitable, but many others are unfair exploitations of the vastly disproportionate power dynamic between longer-term residents and students, who won’t be around long enough to complain. Despite this, I’ve learned to view living off campus as the training wheel version of being a real adult with his own place. As of next year, that is what I’ll have to be. So while I won’t stop complaining about the parts of off-campus life that I see as grossly unnecessary, it’s also important to put it in the context of all of the benefits gained. Even knowing all the downsides, I’d live off-campus again in a heartbeat.

Joe Laposata is a senior in the College.

Wtf is Blue House?