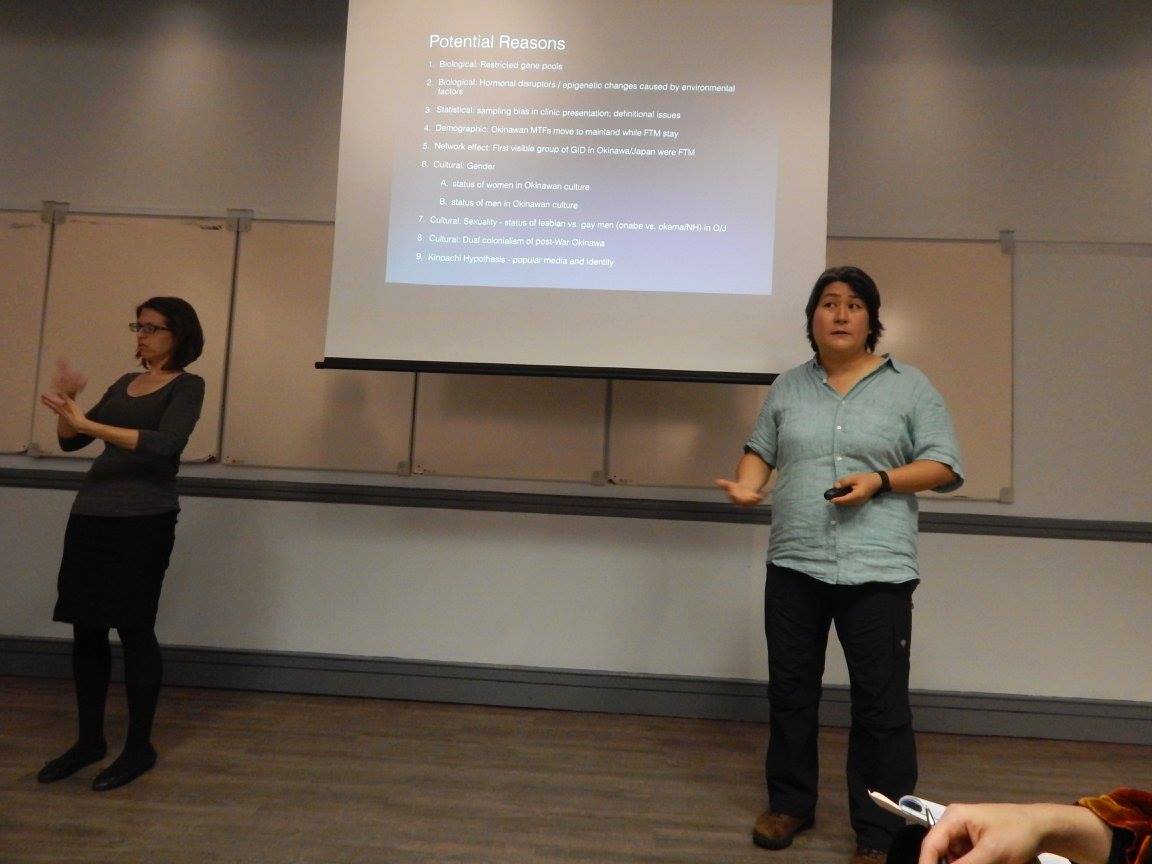

On Oct. 21, the LGBTQ Resource Center held a discussion on how transgender people in contemporary Japan are framing their gender identity as a disability, as part of this year’s OUTober events. Yale University Professor Karen Nakamura shared her research on how Japanese transgender activists present their gender identity as a disability in order to achieve more social and legal change in Japanese society.

Nakamura opened her discussion with a brief history of cross-dressing, transsexuality, and drag queens in Japan before moving on to discuss how transexuality is being represented in modern Japanese society. Nakamura, a cultural and visual anthropologist as well as the chair of LGBT Studies at Yale, has written multiple books on disability in Japanese culture and is currently studying the relationship between transsexuality and disability in Japan.

According to Nakamura, transgender does not fall under the LGBTQ umbrella in Japan unlike in the US, and transgender people have always viewed themselves as being separate from the gay and lesbian community. Nakamura mentioned that throughout history, Japanese society has been relatively accepting of the transgender community. The first transgender surgery was performed in 1958, and drag queens and other male-to-female (MTF) people have appeared in advertisements and on television since the ‘90s. “In Japan, all throughout the ‘80s, ‘90s, and 2000s, male-to-female performers were very visible … the MTF community has always been sort of hypervisible,” said Nakamura.

According to Nakamura, Japanese gay and lesbian communities have never strongly pushed the Japanese for their rights, so many transgender people began framing their gender identity as a disorder to receive medical treatment and fair representation in Japanese society. The official term Japanese people began to use is Gender Identity Disability (GID).

Japanese culture makes it difficult for citizens to identify as both Japanese and anything else, but the term GID has created an entirely new minority group in Japan. “It is very hard in Japan to articulate yourself as a minority … One of the successful minority groups in Japan has been disability rights; that has been one way for people to say ‘I am Japanese, but I am also something else and I would like rights based on my something-elseness,’” Nakamura said.

Nakamura noted how labeling themselves as having a GID has allowed transgendered Japanese to legally change their gender while still being generally accepted in modern society. Japanese transgender men and women have most of the same rights as Japanese cisgender men and women, and in Japan there are not as many barriers to overcome in the process of changing one’s gender compared to the gender transition process in other countries, according to Nakamura. The negative stigma towards transgendered people is also not nearly as strong in Japan as it is in other countries around the world, which may be a direct result of the lack of tension between LBGTQ and religious communities.

“Japan doesn’t have a deep-seated Christian bias against homosexuality, so trans people have more room to operate within society,” said Nakamura.

According to Nakamura, many Americans often question the decision of Japanese transgendered people to align themselves with disability communities rather than with the gay and lesbian community, but framing transsexuality as a disability makes more sense in Japanese culture. Transgender people tend to have closer relationships with doctors and other medical services, and LGBTQ movements have never caught much attention in Japan.

“Having a disability is a strong way for [transgendered Japanese] to articulate this element of difference that is easily accepted by Japanese employers, by their friends, and so forth. Part of this is because the lesbian and gay movement has not particularly had traction in Japan, and articulating that they are like lesbians and gays opens a whole class of questions that they don’t want to answer … ‘Disability’ sounds like a medical condition that can get fixed,” Nakamura said.

“Disability activists have taken the richness of services and support available to them and created a strong movement,” Nakamura said. “Disability is one of the main ways of articulating diversity in Japan.”

[…] and support available to them and created a strong movement,” Nakamura said during a talk at Georgetown University. “Disability is one of the main ways of articulating diversity in […]