D.C. has a complicated relationship with marijuana policy.

The capital of the nation is generally considered America’s gray area when it comes to marijuana legalization. Although previously subjected to stringent federal laws, D.C. residents expressed their approval of the legalization bill, titled Initiative 71, which went into effect on Feb. 26, 2015.

Individuals can grow their own cannabis, smoke in private residences, and gift up to an ounce to others, but any form of sale or public smoking of marijuana is forbidden. While you can likely walk around the city with two ounces of cannabis in your hands—roughly two full sandwich bags of the drug—with no problems, a misstep onto federal land, which comprises 21 percent of D.C.’s total acreage, could result in a felony charge and a year in prison for the carrier. D.C.’s sticky situation stems from its lack of statehood. According to Kate Bell, Legislative Counsel for the Marijuana Policy Project, “D.C. is a weird hybrid because of congressional interference.”

Initiative 71, however, contains a caveat that means a great deal more to the marijuana business community: it legalizes the sale of marijuana-related paraphernalia.

The creation of the cannabis industry is a new and often overlooked element of legalization. A plethora of new careers have emerged, ranging from cannabis gardening shops to event planning for marijuana sharing parties.

In the past, paraphernalia, often called glass or glassware, needed to be sold under a tobacco-related name, typically “waterpipe.” Smoking devices were a constant liability, threatening up to three years in jail on felony charges if law enforcement believed that they were being sold for cannabis usage. Stores would immediately ask a customer to leave if they even said the word bong, because this word alone was enough grounds for police to charge them with sale for drug use.

“Head shops,” named for their “pothead” clientele, have stepped into uncharted territory. What was once a subtle, somewhat seedy business model is now legitimate, presenting new found challenges that come with freedom.

The federal government is in charge of Washington’s budget. So, when a medical marijuana initiative passed in 1998 by

popular vote, Congress proceeded to attach a line item to every D.C. annual budget for the next eleven years, banning any funds from being appropriated to the approved bill. All D.C. initiatives must be budget neutral; no funding can be permitted, allocating liberties but not finances.

Among the most vocal business owners around the issue of marijuana legalization were Adam Eidinger and Alan Amsterdam, co-owners of Capitol Hemp. Capitol Hemp had a reputation for being a less-than-discreet smoke shop. Books about cannabis and citizens’ rights and pot leaf apparel were sold alongside various waterpipes marked “for tobacco use only.”

Eidinger, a longtime advocate of the legalization movement, co-founded the DCMJ advocacy group in 2013 along with a friend named Nikolas Schiller. Additionally, in 2010 Schiller served as director of communications for Eidenger and Amsterdam’s D.C. Cannabis Campaign, which aimed for full cannabis legalization and was later absorbed into DCMJ.

In late October 2011, before it had truly gotten off the ground, their movement was slowed to a grinding halt. D.C. police raided the store with warrants to search for drug paraphernalia. An on-scene test proved positive for THC, the psychoactive chemical that gives cannabis its physical effects. Six people were arrested, and in exchange for dropped charges and the return of nearly half a million dollars in merchandise, Eidinger and Amsterdam were forced to shut down their two Capitol Hemp locations.

After these events, the two, along with Schiller, devoted themselves to legalization, drafting the proposal that would become Initiative 71. Three years and 115,000 supporting votes later, their initiative passed, allowing for every provision except the sale of marijuana.

Capitol Hemp has since reopened, along with many other local smoke shops. The fear of being prosecuted, at least on paper, has disappeared. “The beauty of 71 is that it made that gray area very crystal. That if you wanted to sell a bong, you don’t have to use coded language and call it a waterpipe,” Schiller said. “You could say, ‘you can put your weed in there’ and be direct about it instead of saying ‘put your product in there, put your tobacco in there.” Legally this is a success for the Campaign and cannabis users, yet the competition of a free market has emerged as a new fear.

Schiller described Eidinger and Amsterdam as advocates over salesmen. They are well-informed policy experts pushing for what they consider a civil liberty. But not all D.C. shop owners were so concerned with advocacy. Many owners who sold—and some who continue to sell—glassware under the “tobacco only” title were just concerned with their livelihood. They do not follow the law minute by minute, nor do they preach the legalization message. Beyond this, the impact of legalization is limited by the lack of visibility of this change, as most shop owners still feel the effects of the traditional anti-pot stigma.

Zack Drissi, co-owner of Bazaar Atlas and a father of five who immigrated to the U.S. from Morocco in 1984, is one shop owner who has capitalized on the sale of glassware. A quick glance into his store gives off the atmosphere of a busy flea market stall. Located in Adams Morgan, the shop is cluttered with pile upon pile of various hand crafted goods, most reflecting Drissi’s interest in African Art, including handcarved masks and handbags hanging from the ceiling.

Atop the counter, however, lies a unique portion of this trinket store’s nearly 30 years of success in one of D.C.’s most affluent neighborhoods. Drissi must peek over this section of lighters, glass pipes, bongs, and metallic grinders donning Bob Marley’s dazed grin that clutter the entire front counter in order to speak with his customers.

Drissi previously ran a similar store in Morocco, which he broadly identified as a place for hand crafted goods. Glass pipes were sold as well. He sells pipes simply because they pay the bills, and legalization has not affected his sales much at all.

“The big change for the head shop, the one has all the glass. But you know, really, for me it is like I said: 12 to 10 percent. It’s not much,” Drissi said.

Drissi remains one of the many vendors who has refused to embrace the head shop title. Although he is neutral about legalization, his opinion is that an association with cannabis can only stigmatize his shop and undermine the sale of the countless other items he offers.

“You know what’s something, the glass pipes, they hurt the business. If people come through with the kids … they was thinking I was a head shop.” Although hookah pipes drive a large percentage of his sales, he is fine with taking down his “tobacco only” signs and allowing customers to purchase for whatever purpose they desire.

Scattered throughout Washington, D.C. are various places to purchase paraphernalia. Many like Drissi act with caution, leaving usage of the glass to the buyer’s discretion. One store however, proudly identifies itself as “the only weed shop up in D.C.,” as their sign reads.

Even on weeknights, NoMa’s Island Dyes stays open with bright lights and speakers blasting rap through their open front door. Inside is any possible piece of weed equipment you can think of, all advertised as such. Next to the front door is a large “Thank You for Pot Smoking” sign and a poster of a scantilyclad woman advertising RAW rolling papers.

Since the store opened two and a half years ago, its goal is to be known as a place for people who smoke marijuana. Island Dyes is a small East Coast franchise, with a main location based in North Carolina, and its stance as a paraphernalia shop for cannabis is clear. Although a pre-legalization world forced them to use different terminology, their target audience was clear.

Since the store opened two and a half years ago, its goal is to be known as a place for people who smoke marijuana. Island Dyes is a small East Coast franchise, with a main location based in North Carolina, and its stance as a paraphernalia shop for cannabis is clear. Although a pre-legalization world forced them to use different terminology, their target audience was clear.

Both Island Dyes and Bazaar Atlas, as vendors of paraphernalia, are keenly aware of what they are and what they wish to be. Drissi has been slowly moving his glass pieces away from the front of his shop as they scare away certain customers. He faces a daily tradeoff for this 10 percent of his yearly earnings, “I had [pipes] for the last almost 25 years, but still people didn’t want to come to the shop anymore because of the glass pipes.”

Even before legalization had been fully implemented in early 2015, shop owners have been seeing the effect of an over-saturated, niche market. Despite cannabis proliferation, Island Dyes and Bazaar Atlas report relatively little increase in their business, head shop title or not. This is challenging in a place like D.C. where urban planning trends have put the squeeze on small businesses. Bazaar Atlas is locked into a 3 percent rent increase every five years. D.C. has seen gentrification and massive infrastructural overhaul. In Adams Morgan alone the median home value is $552,700, marking an increase of over $100,000 since 2010 according to Zillow.

Schiller, of the D.C. Cannabis Campaign, is aware that this newfound freedom to sell cannabis paraphernalia has not given glassware proprietors any mercy from the free market. Looking toward the future, Schiller said that embracing the pro-cannabis culture would aid shops struggling to stay in business.

“The people that are quiet about [legalization] generally aren’t advocates, they’re just businessmen. And they don’t want their names out there even though they don’t realize having their name out there and being an advocate brings them business,” said Schiller. “It might resonate with people that see that ‘hey this guy is doing the right thing I’m going to support his business.”

It may be too late in some regards, as everywhere from liquor stores to gas stations edge in on the profit by setting up a glassware shelf. The market is saturating, which may explain why Island Dyes and Bazaar Atlas have seen very little improvement in the amount of glassware they sell. Drissi claimed that six new stores have opened up in his neighborhood of Adams Morgan alone, all trying to capitalize on the market.

These openings also do not take into consideration other entrepreneurs trying to profit from Initiative 71. Glass sales are only a portion of the business models active in D.C. cannabis culture. Just a few doors down from Drissi’s shop is the easy to miss Grow Club D.C. Inside is a mix of a hippy trinket store and practical place for gardening supplies. Tie dye backpacks and pot leaf t-shirts hang on hooks while brightly colored watering cans and plastic picket fencing. The owner of the shop is Eddie Williams, D.C. resident, entrepreneur, and recreational cannabis enthusiast.

Williams opened up his shop 18 months ago, inspired by his city becoming the first place on the East Coast to enact legalization. He began to grow his own marijuana for personal consumption, and the deep satisfaction of successful crop yields led him to a business model of his own.

“We started thinking and pondering, and it was like, ‘well let’s just help other people to grow, and start their grows.’ So that’s what we started doing. We wanted to be different from other people, so what we did is we started to build custom cabinets, grow cabinets.”

Williams sells, installs, and offers monthly checkups on hydroponic– waterless cultivation tents for marijuana plant growing. Initiative 71 permits individuals living in D.C. to grow six marijuana plants in their residence, or 12 if more than one adult lives in the residence. The store is designed for the city’s peculiar laws and cityscape.

“We wanted to be unique and different, and kind of capitalize on D.C.’s smaller space and level of discreteness. With the government and everything, a lot of people work for the government and still smoke, but they want a level of discreteness instead of having a big tent in their room or house,” Williams said.

Grow classes are available for paying members, and with the paid membership comes

Grow classes are available for paying members, and with the paid membership comes

something even more unusual: free cannabis. Anyone who pays for classes can receive weed in the form of seeds; clones, a cannabis plant that grows after being cut off of another “mother plant;” edibles, cannabis cooked into various baked goods or candies; or smokeable cannabis. The practice is allowed within the confines of the law.

This special gift is what keeps his business model thriving. Even the tent selling field is being flooded with competitors. Williams sees these trends in his city, comparing it to the inundation of websites and economic boom created in the dotcom bubble of the mid to late ’90s. Many stores, less concerned with quality or a comprehensive business model, have suddenly emerged.

“I would say that their business has been cut into drastically by the Initiative 71 movement … it’s cutting into those businesses that strictly rely on selling glass pipes and bongs and stuff like that,” Williams said. Independent vendors are among this new group entering the market. Not weighted down by storefront rent or other various forms of overhead, they are making easy profit.

Some businesses, like Island Dyes and Grow Club, continue to thrive through their community. D.C. is stuck in a legalization stasis, and the cannabis community is adrift together in an unclear legal system. William’s system of classes and home installations turns customers into loyal, familiar faces. Island Dyes, with its broader base, has adapted to the new law by offering new services like custom bong repairs and cleanings.

Although people are still being arrested for selling marijuana in D.C. and given lengthy sentences, Drissi, and Williams, have only had positive experiences with law enforcement since Initiative 71 was passed.

“As long as you don’t do anything super blatant, absurd, gift and donate to kids, and don’t ride around in cars that are wrapped with weed over it, f*ckin’ smoke right next to a cop, it’ll be alright,” Williams said.

A great deal of problems with the law come from genuine ignorance. Island Dye’s proximity to Union Station generates out-of-towner foot traffic, and Adam’s Morgan’s famous shops and nightlife have a similar effect on visitors. Williams is acutely aware of the problems generated by the confusing nature of D.C. cannabis law.

“A lot of out-of-towners think it’s like Colorado out here. They really think you can just go in here, go into a dispensary, and just get weed openly. And you have to kind of let them know that, no, it’s not like that at all.”

Stores are no longer being raided for their paraphernalia, and the overall relationship with law enforcement has improved as a result. Nikolas Schiller himself is a cannabis user who enjoys this more transparent relationship. “I would say there is a better trust with law enforcement, because in the past if there was something on you, you’d be afraid that you couldn’t go to the police for something because you’re a criminal and now you’re not,” he said.“There’s a certain amount of freedom that comes back with that.”

Although the Metropolitan Police declined to comment, D.C. police officers have received updated training modules to ensure they know the specifications of the new law.

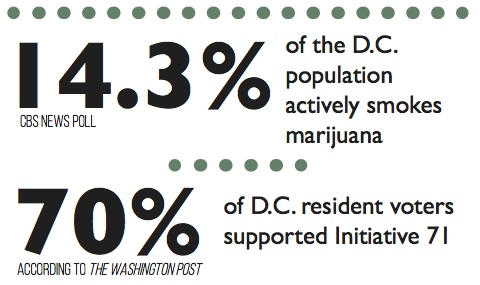

A lot has changed since President Richard Nixon first declared the war on drugs. D.C. is now one of the many places in the United States well on its way to full legalization. A recent CBS study found that 14.29 percent of the D.C. population actively smokes marijuana, and, according to the Washington Post, nearly 70 percent of voters supported Initiative 71.

A lot has changed since President Richard Nixon first declared the war on drugs. D.C. is now one of the many places in the United States well on its way to full legalization. A recent CBS study found that 14.29 percent of the D.C. population actively smokes marijuana, and, according to the Washington Post, nearly 70 percent of voters supported Initiative 71.

For now, the D.C. cannabis community can only expand through the generosity of others and their own willingness to participate in the process. August 2016 marked a setback for the movement as the Obama administration rejected a bid to put this drug, currently classified as a Schedule 1 Drug under the Controlled Substances Act, up for reclassification.

Eddie Williams and people like him, however, are confident in what the future holds for D.C. statehood and a fast track to full legalization.

“D.C. now has money [due to recent gentrification], they didn’t used to have this amount of money they have now 10 years ago, 15 years ago. They were always reliant on ‘taxation without representation’ right? Always relying on the Feds, now they have all this money, and they’re like f*ck you I can stand up on my own. This is actually the most realistic time for them to become their own state.”