Stories of sexual assault are incredibly difficult to tell. This book, and my column, simply try to do so. Also, I acknowledge that different Native communities prefer different identifying terms (“Native American,” “Indian,” “American Indian,” etc) For the purposes of continuity in this column, I will use “Native American” and “Native.”

Louise Erdrich’s novel, The Round House, artfully weaves the narrative of 13-year-old Joe, an Ojibwe Native American whose mother is brutally raped by an unknown attacker. The first part of the book is dedicated to Joe’s mission to discover the attacker’s identity, as his mother refuses to speak about it. Once they discover the perpetrator, revenge becomes Joe’s goal.

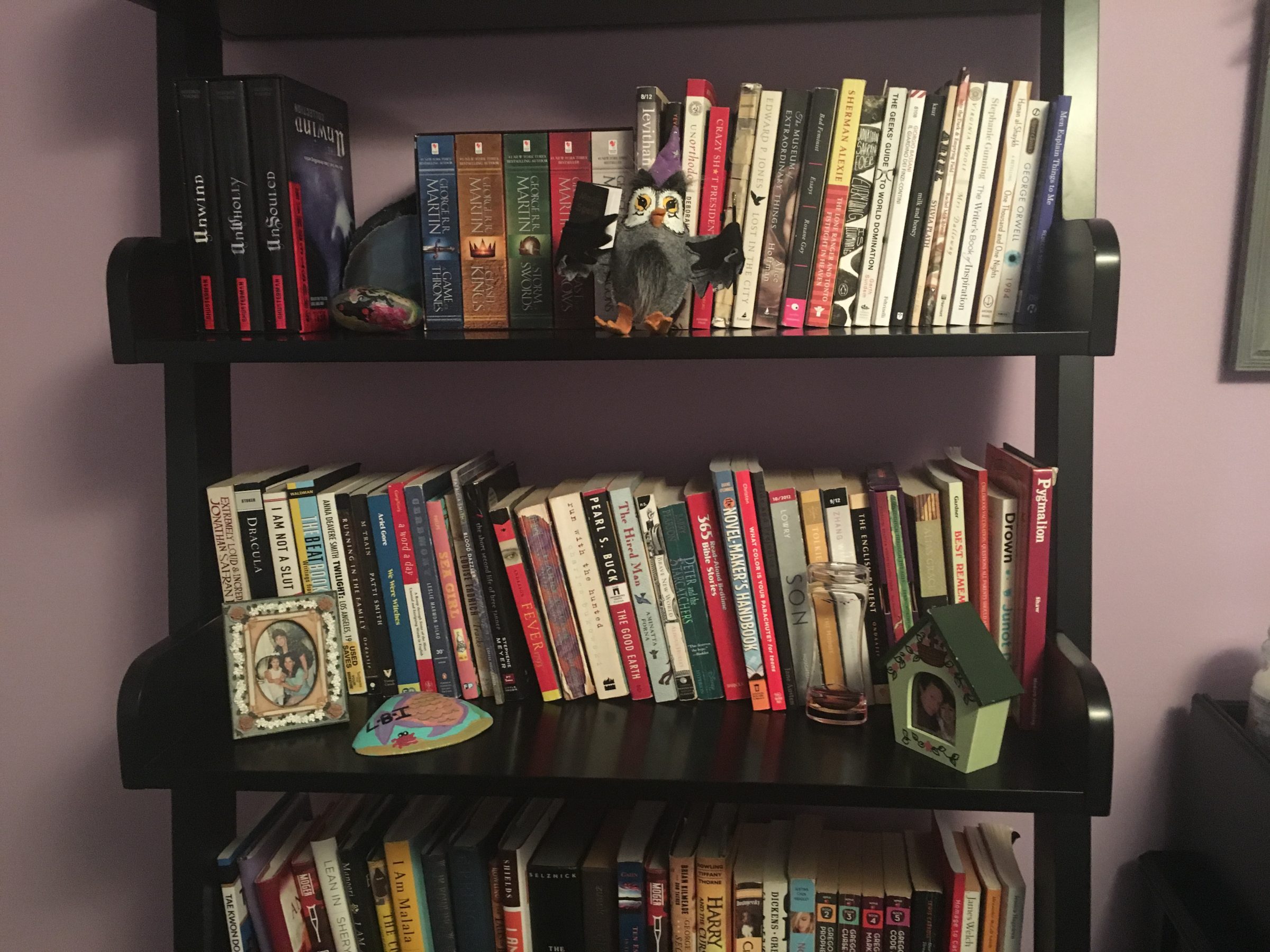

I was introduced to Erdrich’s writing in my Native American literature class freshman year of college. I loved her novel Tracks, so when I saw this one on display in a local bookstore last summer, I jumped at the chance to get it.

I love this story’s complexity, its emotional rawness, and the decisions Erdrich makes about perspective and point of view.

Erdrich chooses to tell the story from a 13-year-old boy’s perspective. He’s only just started to evolve into a man, constantly comparing his physical features to those of his friends. He begins to develop emotional maturity when he is thrust into the adult world, horrifically and without warning.

By telling the story through Joe’s eyes, the reader discovers details along with him, a boy too young to automatically understand the meaning and implications of rape. Sometimes it’s even more awful to receive such heavily physical, defamiliarized descriptions of events because they’re one step removed from the commonly known thing. The reader then experiences the same moment of shock and horror when Joe fully realizes the brutality of what has occurred.

For example, Joe remarks that his mother smelled strongly of gasoline when she was discovered. He doesn’t understand why that would be, but he is very uneasy about it. Then, the moment of impact. She was doused in gasoline because her attacker had planned to burn her alive, and he would have if she hadn’t escaped.

This decision on perspective also makes his mother feel even more isolated, as she separates herself from her family to work through her trauma. Her trauma is not exploited through constant description and explanation of every moment. Instead, we experience it filtered through someone who cares about his mother as innocently and wholeheartedly as any 13-year-old boy would. But we also see his frustrations, his immaturity, his retaliation against her for not complying with the investigation easily, for no longer being a strong mother figure.

Describing her trauma through her son also somewhat absolves Erdrich of the responsibility of telling her story from her own perspective. The decision not to make the mother the main character doesn’t feel disempowering. Rather, I see it as an effort on Erdrich’s part not to claim the mother’s story as her own (however fictional, it is based in the hard reality of endemic sexual assault of Native American women). Erdrich wants to emphasize the emotional impact, but she doesn’t presume to know every single feeling of a rape survivor.

Erdrich doesn’t center the plot around a big “aha!” moment revealing who the rapist is, although at the beginning it seems as though it might. The perpetrator’s identity is unveiled surprisingly early in the book, and the latter half is dedicated to Joe’s efforts at avenging his mother’s attack. By not hinging the reader’s interest and attachment to the story on an “aha reveal,” Erdrich honors the victim rather than exploiting her. She makes the point that it’s not always about who did it.

Sometimes it’s about the survivor. Sometimes it’s about the mark the attacker leaves behind, about the consequences and long-term implications. Sometimes simply knowing who attacked you doesn’t actually do anything to improve the situation.

Joe’s revenge quest against his mother’s attacker takes a very righteous turn. Thoughts of violent revenge consume him as he vows to avenge his mother. He deceives his family and friends in preparation to exact his vengeance. But he comes to see his drive not as a desire for vengeance but rather for justice.

When trying to avenge his mother and satisfy his bloodlust for her attacker, Joe traumatizes himself in the process. He starts drinking heavily to numb the pain and dull the memories, and his stomach writhes in permanent knots. His efforts reveal the power of friendship but also the great capacity for violence that Joe discovers within himself.

The very last page takes an even more gruesome and unexpected turn. I had to reread the final page three times to be sure that I correctly understood what happened. This turn proves that the guilty will never find themselves free.

While Joe is forced to grow up in many ways, he is still an immature 13-year-old boy, sexually inexperienced and perpetually thinking about it.

Joe’s Aunt Sonja (not blood-related) is the object of his sexual focus. He constantly describes her breasts, outfits, and sexual allure, commenting repeatedly that she used to be an “exotic dancer.” In a disturbing scene, Sonja degrades herself for the pleasure of Joe and his grandfather, to satisfy their leering gaze in a way that is at once exciting and sickening. She is coerced into dancing for them, removing her clothes, performing, being who they want her to be.

Things aren’t black and white in The Round House. Sonja calls Joe out on being “just another gimme-gimme asshole,” just another disrespectful, crude man who only wants to gawk at her, lust after her, rather than have a meaningful familial relationship. Joe’s objectifying gaze is not the same thing as rape, but it is still inappropriate and violating. This complexity in Joe’s character shows that he can wholeheartedly desire to avenge his mom while also being another immature, asshole guy.

This book also confronts sexual assault in the Native community. Often, the laws do not work in women’s favor. So much rides upon where the rape occurred, whether it be tribal land or government-owned land, and upon whether the perpetrator was Native American or not. Joe’s mother can’t remember where the rape took place, which causes problems in prosecuting her attacker.

When she recounts her attack for the authorities, her husband insists that a state trooper, a local town officer, and a member of the tribal police are present. Joe knew that the questions of “who” and “where” would complicate but not change the facts, “But they would inevitably change the way we sought justice.”

The government generally classifies Native Americans as such by examining their history and blood quantum. They need to have ancestors who registered as members of a federally recognized tribe, and they must possess one quarter Native blood, belonging to one tribe. “In other words, being an Indian is in some ways a tangle of red tape,” Erdrich writes.

Native identity is central to the story because it greatly impacts the ability to prosecute rape cases. The court case Oliphant v Suquamish stripped Native communities of the ability to prosecute non-Natives who commit crimes on their land. So, even if Joe’s mother’s rapist committed the crime on tribal land, they can’t prosecute him if he’s not Native.

According to a report by Amnesty International, 1 in 3 Native women will be raped in her lifetime (and rapes often go unreported, so that number is likely higher). 86 percent of rapes and sexual assaults upon Native women are perpetrated by non-Native men. Clearly, rape is a severe threat to Native women, and our laws do very little to protect and defend them.

Nothing is uncomplicated when it comes to matters of guilt, justice, and revenge. Joe is not a perfect boy hero, and his mother is not a “perfect victim.” Her recovery is not easy or smooth or dismissable. It is in your face at all times. It is traumatizing. It hurts those around her. She is not idealized or sensationalized. And neither is Joe. Joe is knocked down to size, toppled from his pedestal, just like everyone else is at some point in their lives. Even the admirable main character can commit atrocities in Erdrich’s world, as in life.