Andrea Tacconi remembers a day when a young girl could not get medical treatment at school because her family only spoke Spanish. In her written testimony to the D.C. Council in April 2017, she recounted the incident, which occurred when she worked for Teaching for Change, an educational non-profit based in the District. To receive treatment for the girl’s fever, her family would have had to fill out English-language forms. When the girl’s mother approached the school to seek a translation from English to Spanish, the school did not have enough Spanish-speakers on its staff to help the family provide documentation for their child, leading her to be denied treatment by the school.

This story is one of many that have inspired a decade-long struggle to lower the daily barriers for non-English speakers in Washington, D.C. The campaign reached an important milestone last month, when the D.C. Council officially passed the Language Access for Education Amendment Act. The council voted unanimously with one absence to approve the bill, which alters a 2004 law mandating that the D.C. government provide all residents equal access to government activities and services, regardless of their English abilities.

The 2004 bill made the District a pioneer in providing expanded government resources to people identified as Limited English Proficient (LEP). But language access proponents have since grown frustrated with the law’s limitations. Advocates argued that its mandates were not universally enacted by its intended targets, causing the bill to fall short on many of its stated goals to ensure that non-English speakers in the District can access government services. Seven members of the council introduced the 2017 amendment as a corrective measure.

The fight in the District for language access rights is a microcosm of a larger, nationwide push for greater accommodation of non-English speakers.

“These people are largely immigrants who are not English proficient,” said Yemisrach Wolde, coordinator of the D.C. Language Access Coalition. “They are paying their taxes, they’re contributing to society. We have to step away from always pleading that our rights are at least as important as everyone else’s.”

“This is a right, it should be provided, that’s it. That’s my argument, and I think it should suffice.”

***

Importantly, language access is viewed by organizers and advocates as so fundamental that it is a separate issue from the protections against discrimination provided by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which states that no person shall be discriminated “on ground of race, color, or national origin.” Broadly defined, language access in the United States concerns the ability of non-English speakers to take full advantage of services, programs, and activities that English speakers regularly use.

Many states and municipalities have followed federal guidelines on language access, which generally require means to translate documents for essential services and having a language access implementation plan. Some have also mandated different, more expansive requirements for their language access laws, following President Clinton’s Executive Order 13166 in 2000 that required federal agencies to devise language access plans. In Washington, D.C., one part of the 2004 law stipulates that government programs, departments, and services “provide written translations of documents into any non-English language spoken by a limited or non-English proficient population that constitutes 3 percent or 500 individuals” who are served by that agency.

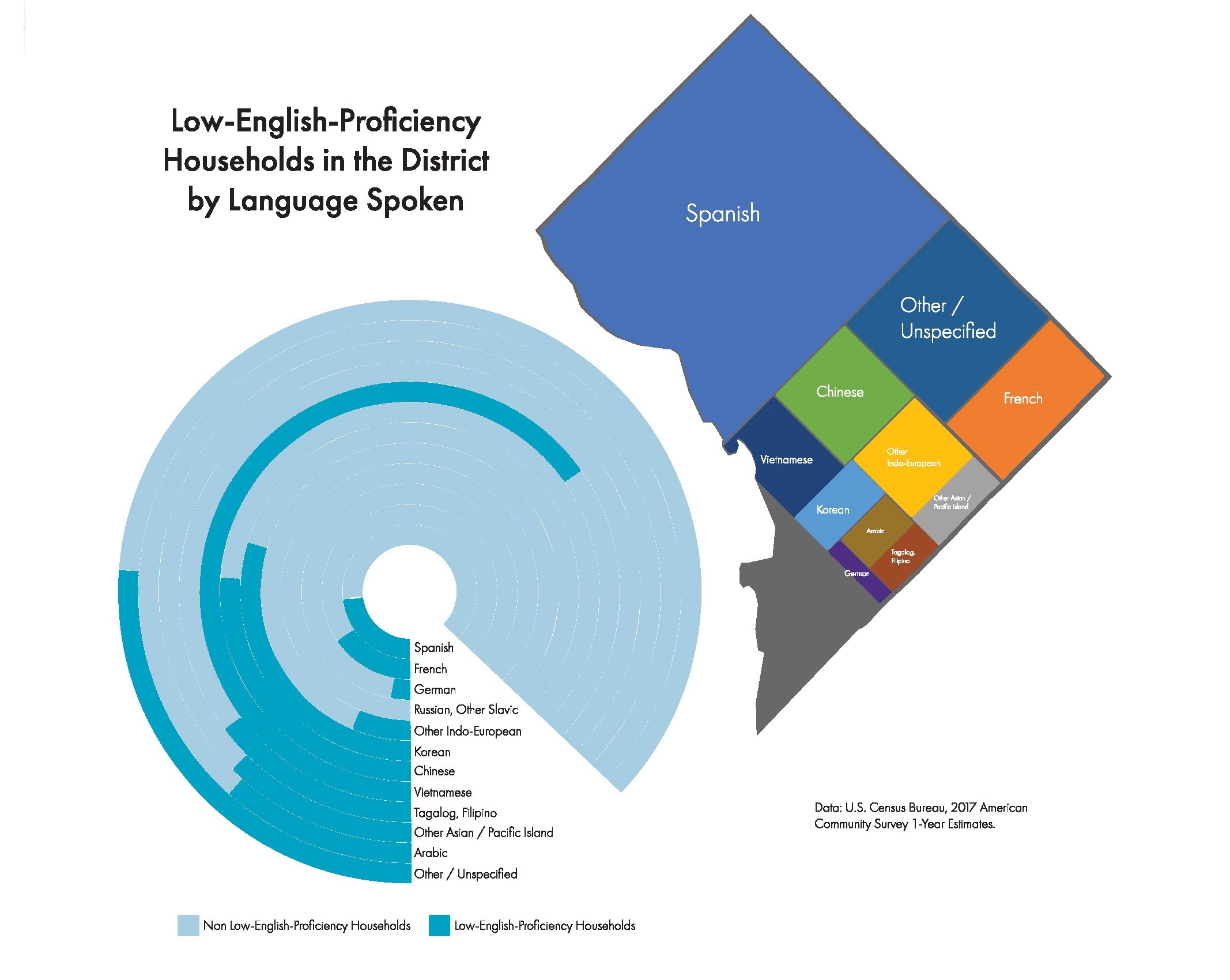

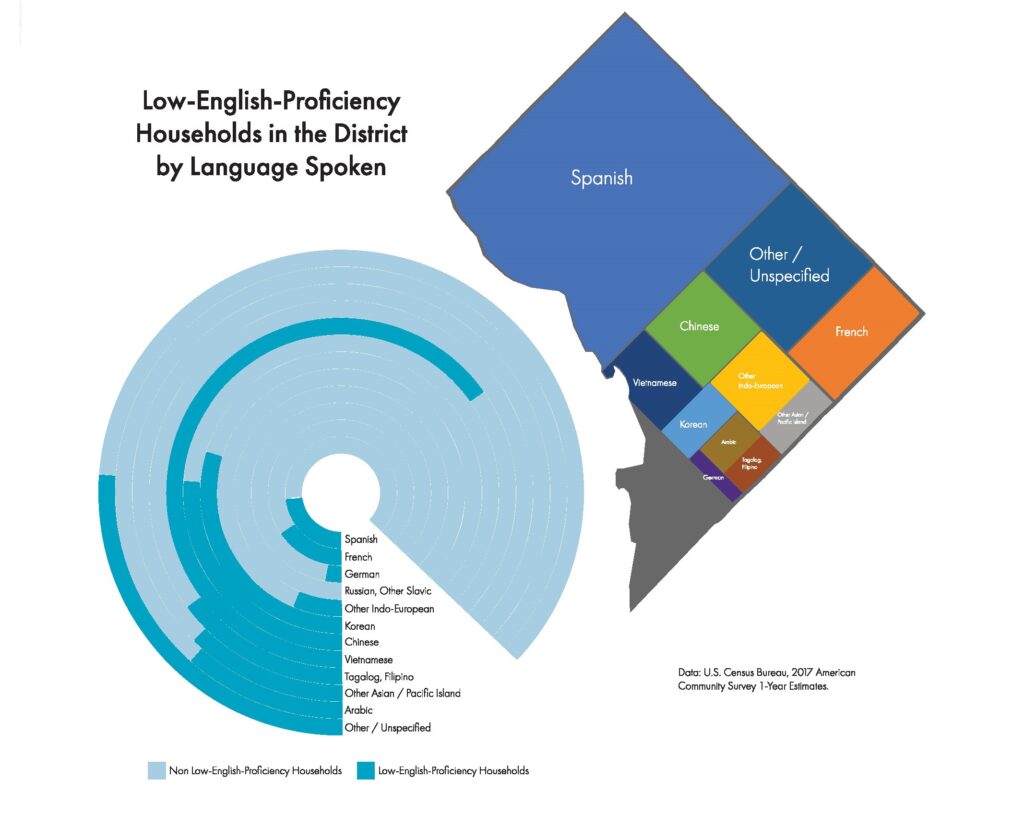

Despite the existing requirements, evidence and trends from the past few decades suggest a greater need for language access in the District and throughout the United States. A report by the Migration Policy Institute found that the adult population in the country identifying as LEP has swelled from 11.6 million in 1990 to more than 22 million in 2015. In the District, foreign-born individuals account for over a third of the population growth since 2007, according to a 2014 report by the Urban Institute.

Today, the demand is even more pronounced, as approximately 95,000 city residents, or roughly 14 percent of the city’s total population, are immigrants. Additionally, no single country of origin comprises more than 16 percent of the foreign-born population. The D.C. Office of Human Rights (OHR), which oversees complaints of violation of the Language Access Act, has identified six languages with a sizable enough population of speakers to necessitate further language access accommodations: Amharic, French, Chinese, Spanish, Vietnamese, and Korean.

But even now, 14 years after the first language access bill became law, city and school services are not always available in those languages. Advocates, city officials, and non-English speakers have grown frustrated with the rocky implementation of the law.

Despite an overarching mandate, each individual agency is responsible for funding its own language access services, resulting in an uneven distribution of resources across agencies, according to the Urban Institute report. This decentralization, as well as anecdotal evidence ranging from Tacconi’s testimony to stories of non-English speakers being ignored by D.C. government agencies, demonstrates the challenges that D.C. agencies have faced in providing language access to LEP residents.

Against this backdrop of disappointment with the original law, the D.C. Council passed the amendment, which created several new requirements. The bill increases the number of “covered entities”—programs, departments, and services with “major public contact”—who are subject to the original Language Access Act. Another new condition of the amendment is that public and charter schools have to provide translations of “essential information” to students, parents, and guardians. Additionally, local education agencies, including D.C. public and charter schools, must designate a dedicated language access staff, consisting of a language access coordinator and language access liaison. Other components of the amendment clarify OHR’s complaint filing and appeals procedures and allow OHR to levy $2,500 fines on covered entities for violations of the Language Access Act. In theory, even though agencies are still responsible for funding their own language access divisions, the fines provide greater incentives for compliance with the law.

The nuances of the amendment, as well as its volatile journey, belie its quiet passage in the D.C. Council. Nonetheless, some language access advocates believe the new law is still incomplete. Following the 2004 law, the Language Access Coalition, a group of organizations which promote language access in the District, has pushed for additions to the law. One such proposed addition is a legal cause of action which would allow individuals to take noncompliant organizations to court. The original law was silent on the issue, and the coalition wanted to codify this legal recourse. The new law, however, specifically bars this; instead, OHR has the ability to award the fines it levies to complainants.

The cause of action was one of the primary “teeth” the coalition had been fighting for, and its exclusion from the final version of the law has left some advocates dissatisfied. Allison Miles-Lee, managing attorney for Bread for the City, an advocacy group in the Language Access Coalition, described the reaction as one of discontent.

“There’s certainly disappointment amongst advocates,” Miles-Lee said. “I wouldn’t say this is a total win for the community in that it got everything that everyone wanted, and I think people are disappointed because it feels like people weren’t heard.”

Wolde was also disappointed with the outcome of the amendment, citing the omission of a cause of action provision as an example of D.C. government shirking responsibility.

“It’s very disappointing,” Wolde said. “Government agencies, again, are trying to be less accountable. A private right of action is supposedly an inalienable right.”

Testimony at D.C. Council hearings from politicians, including Councilman Phil Mendelson, and school officials may have played a role in striking the private cause of action, as well as the elimination of fines for schools. Miles-Lee noted that while private cause of action was in the works, Mendelson advocated for its removal.

“[He] was concerned it would open up the government to being sued constantly,” Miles-Lee said.

Some critics of the new plans for language access coordinators have pointed to the costs they impose on schools that are already strapped for resources. This argument was a part of the drive toward exempting D.C. public and charter schools from the $2,500 fine. Brian Pick, chief of teaching and learning at D.C. Public Schools, said as much during an April 2017 D.C. Council hearing.

“While federal Title VI already requires school districts to provide information to parents when necessary in their required language, we have overall concerns about the schools’ capacity to translate and pay for the broad range of documents identified,” Pick said at the hearing.

But Lee is skeptical of claims that the new provisions would create more fines, and thus more paperwork and overhead costs for agencies. She said the agencies need to be more willing to adapt to the law’s stipulations.

“The law is what it is, so if you follow the law you’re not going to get fined,” Lee said. “We’re not creating a new right here for people. That’s already been decided. [Language access is] a right that people have in D.C.”

As for what advocates can continue to do in the meantime, Wolde emphasized the importance of engagement with LEP communities.

“It’s not just about raising awareness,” said Wolde. “It’s about letting people know that they are powerful.”