At the end of the 2019 regular season, the top four records in Major League Baseball should not have been a surprise: the Astros, Dodgers, Yankees, and Twins all put up 100+ win seasons, with the Marlins, Orioles, Tigers, and Royals suffering from brutal seasons of under 60 wins. In today’s MLB, this oligopoly of competitive clubs seems to be the new normal; with superteams at the top, a few challengers nipping at their heels, and a lot of mediocre teams hoping to be the future powerhouses who dominate the MLB. In an age where baseball is portrayed to be a “dying sport,” what can explain this newfound consolidation of talent and lack of parity in the game?

It all comes down to the classic debate of money in baseball, and the inability of small market teams like the Marlins and Padres to compete with big market clubs like the Yankees and Dodgers. While the NBA, NFL, and NHL all have salary caps to limit teams with deep pockets from spending absurd amounts of money on superstars, the MLB still does not have a salary cap, and instead attempts to curb spending through other measures, such as a luxury tax. However, the MLB’s current policies are inadequate for closing the gap in teams’ disposable income, which affects their performance on the field. In this article, I will take a deep dive into the competitive landscape of baseball, and analyze the infrastructure and rules that the MLB has in place to balance competition and limit the impact of financial status on a team’s performance. Then, within the context of the rules of the game (sorry, Astros), we will look at the different ways in which teams are managing their situations, and suggest potential solutions for how the league can create a more competitive environment for baseball.

The Competitive Landscape of Baseball

In an explosive interview a few years ago with ESPN radio host Dan Le Betard, MLB commissioner Rob Manfred claimed that the lack of parity in the MLB comes from a byproduct of baseball as a “cyclical business,” where teams have periods of contention followed by periods of rebuilding. While it is true that, in general, professional sports teams go through cycles of successful and catastrophic seasons, Manfred misses the fact that the window for contending in baseball is tied to payroll, as periods of success are more frequent and sustainable for large market teams than for small market teams.

We can measure this disparity in performance by taking a team’s number of 95+ win seasons, or “contending seasons,” and compare that with their number of 70-and-under win seasons, or “rebuilding seasons.” When taking payroll into account, and comparing a team’s difference between the two types of seasons over the last 20 years, it is shocking how closely a team’s performance ranking matches their average payroll ranking. Here is a table comparing payroll to winning and losing seasons (click on this link – recommended zoom is 50%):

It is important to note that nine(!) teams’ performance rankings can be predicted within one rank by their payroll, or general ability to spend on their roster. Nine teams is over a quarter of the league, which carries more weight when we take into account that only five teams (a sixth of the league) have win rankings that differ by double digits from their payroll ranking. Congrats to the A’s, who are most efficient with their payroll, jumping up 21 spots from their payroll ranking to their win ranking. I’ll talk about how they were able to do this later.

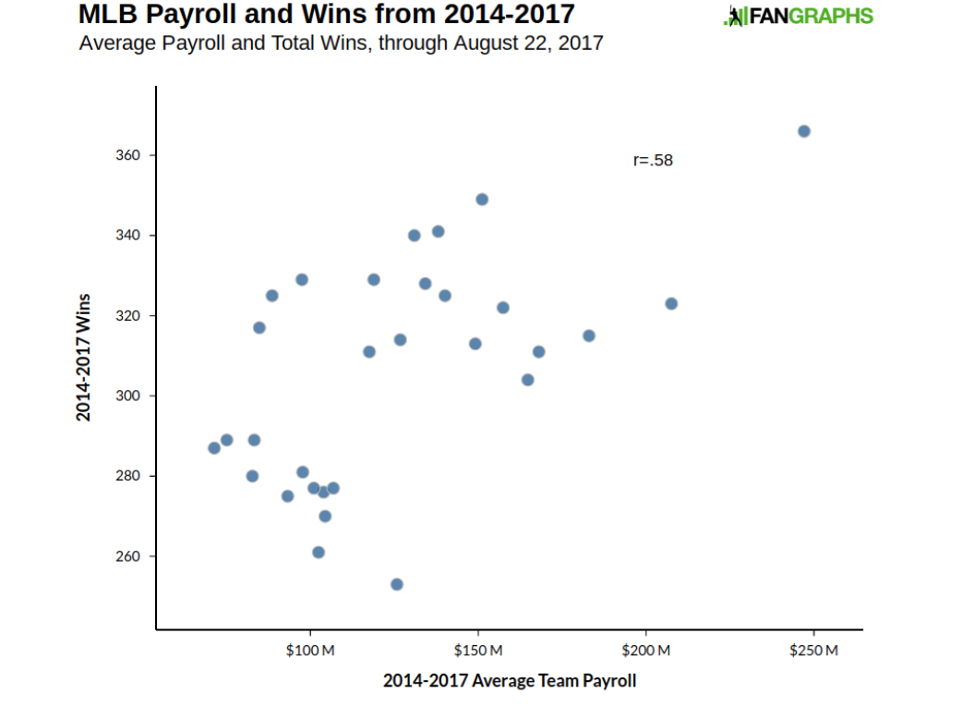

By comparing 20 seasons of baseball, we can remove the “luck” or “cinderella season” component from the equation, since injuries, locker room issues, and other external factors can lead to luck determining the outcomes for teams in singular seasons. Fangraphs did an informative scatter plot on wins and payroll, and found the correlation between the two variables to be fairly weak over one season, but much stronger over the course of a few seasons. Here is the scatter plot from their website below (and feel free to click on the link to their webpage):

Source is linked here.

The fact that 58% of the variation in wins (over a few seasons) can be explained by a team’s payroll is significant. When adding the fact that, on average, a team can only move up or down by 5 slots in their win ranking based on their payroll, there is evidence to claim that success in the MLB can be predicted by payroll. We can also look at the “cycles” that Commissioner Rob Manfred was talking about, and compare the lengths of the cycles between teams (clumps of green and red seasons in the table). A quick look at the data shows us the clear differences between large and small market teams’ windows of contention. Furthermore, consider the “standard deviation” of win totals in the MLB, and we find that in just the last two seasons, the MLB had two of its top three highest standard deviation totals of the last 20 seasons. This means that the win totals of clubs in the last two seasons were the most widespread in recent history. So what causes the payroll differences in the MLB that lead to this lack of parity in the league? To answer this question, I will look at the current system that the MLB has in place, and determine the extent to which these policies address the disparities in teams’ payrolls and their ability to acquire, nurture, and keep their talent.

MLB Rules and Regulations Affecting Payroll

The MLB rule that is most directly related to payroll is the competitive balance bax (also known as the luxury tax), which is the MLB’s version of a soft “salary cap,” intended to discourage teams from spending extreme amounts of money on their players. According to MLB.com, here were the thresholds for the luxury tax over the last three seasons, with the upcoming two seasons included:

2017: $195 million

2018: $197 million

2019: $206 million

2020: $208 million

2021: $210 million

While these figures seem reasonable when given the distribution of MLB payrolls, the luxury tax is not a substantial penalty for clubs who have the resources to exceed the threshold. MLB states the penalty for exceeding the luxury tax is as follows:

“A club exceeding the Competitive Balance Tax threshold for the first time must pay a 20 percent tax on all overages. A club exceeding the threshold for a second consecutive season will see that figure rise to 30 percent, and three or more straight seasons of exceeding the threshold comes with a 50 percent luxury tax. Clubs that exceed the threshold by $20 million to $40 million are also subject to a 12 percent surtax. Meanwhile, those who exceed it by more than $40 million are taxed at a 42.5 percent rate the first time and a 45 percent rate if they exceed it by more than $40 million again the following year(s).”

In 2019, the Cubs, Yankees, and Red Sox exceeded the luxury tax threshold, with Boston accepting the penalty for the second straight season. Teams can easily afford to go over the luxury tax, because the taxes are only applied on overages, not the total payroll. Now, considering the fact that payroll and wins are positively correlated, it makes sense for franchises to pay a small tax relative to their total payroll in order to win. Since consistent winning energizes fan bases, it is also a wise business move to exceed the luxury tax and recoup the costs of the penalty from the extra revenue generated by the team’s success.

A second rule that addresses the burden of franchises’ inabilities to spend on players is the competitive balance draft. In the amateur draft, there are draft slots reserved after the first round and second round for clubs with the smallest revenues and markets. MLB summarizes the rules on their website:

“The 10 lowest-revenue clubs and the clubs from the 10 smallest markets are eligible to receive a Competitive Balance pick (fewer than 20 clubs are in the mix each year, as some clubs qualify under both criteria). All eligible teams are assigned a pick, either in Competitive Balance Round A or Round B. Round A falls between the first and second rounds of the Rule 4 draft, while Round B comes between the second and third.”

For small market, low revenue clubs, the competitive balance draft also includes an increase in international bonus pool money, which is used by clubs to acquire international amateur players (players outside of the US). International bonus pool money is the amount that clubs are allowed to spend on international amateur free agents, and this is a critical source for teams who are searching for young talent, especially in today’s game. The MLB states that “each club will have at least a $4.75 million bonus pool to spend, with those that have a pick in Competitive Balance Round A receiving $5.25 million and those with a pick in Competitive Balance Round B receiving $5.75 million.”

While the competitive balance draft seems to ease the burden of small market teams by giving them more access to young talent, it is difficult for clubs with limited resources to have the infrastructure in scouting and player development to find and nurture talent. The MLB draft is notorious for being hit-or-miss; the lack of standardization at the amateur level and the unpredictability of players’ development curves makes it difficult and rare for MLB scouting departments to be comfortable and certain with what they are getting in a prospect. Furthermore, it is expensive to build a strong scouting department and pay for travel, especially for scouting international prospects. Consequently, teams with more resources, who also spend more on payroll, are better equipped for discovering and developing young talent. Therefore, the extra competitive balance draft picks and international bonus pool money are helpful, but not sufficient for leveling the playing field between big spenders and penny-pinching clubs.

A third MLB structure that affects payroll and competition is service time. Service time is crucial for determining a player’s salary, and makes baseball a unique sport because a team “controls” a player for the first six seasons in which they play in the MLB. Teams have exclusive rights to a player over this period of time, and “service time” is defined as the time period in which a player is on the major league roster. In terms of the implications of service time on a player’s salary, the cycle is as follows:

- For the first three years of service time, a player’s contract is typically one year with the salary around league minimum. This contract can be renewed by the club at the end of each season.

- Once a player hits their fourth season of service, they are eligible for salary arbitration. This is where the player and the team share figures for a player’s salary for next season, and if no common ground is reached, then a panel of arbiters determine which side’s figure (player or team) is a more fair representation of the player’s value. Players and teams typically avoid arbitration, as it is a messy, demoralizing process that can harm the relationship between a player and the team.

- After a player reaches six years of service, then they are eligible to be an unrestricted free agent. Teams may extend a one year qualifying offer (equal to the mean of the league’s 125 highest paid players), and if an impending free agent rejects it (which they usually do), then the team is eligible for draft pick compensation should they lose that player to free agency.

Despite the fact that teams have full ownership of young talent for their first six seasons in the majors, it is difficult to build a young core and keep that talent together once a team becomes competitive. There is plenty of research on aging curves in baseball, but the consensus for a player’s “prime age” seems to be around the 26-28 range. Considering the fact that most high school amateurs are 18 and college graduates are around 21-22 when they are drafted, and then typically have to play a few years in the minors to establish their talent, this six year-window to keep a player doesn’t exactly line up in an optimal way with the aging curve. Players who arrive in the majors at an early age and reach their “peak” in their last years of team control would demand large contracts for free agency, which is not affordable for small market teams who must maintain low payrolls. Players who arrive in the majors at a later age will experience their “peak” early and decline over the life of a team’s control, which delivers low value to clubs. Therefore, it is no surprise that it is difficult for small market teams to “time” their window of contention, because unlike large market teams, teams with limited resources can not afford to sign big ticket free agents and stack their rosters with prime-level talent. Small market teams must rely on young players to build their cores, but once their star players “graduate” and become free agents, these players are poached by teams who can afford large payrolls. Furthermore, as discussed earlier, it is difficult for teams to get a “hit” on most of their prospects, so in order to build a young core in the first place, a small market club has to build flawlessly. For these reasons, the team control system is inefficient for balancing competition between small market and large market teams, and is a reason for the lack of success and prolonged cycles of mediocrity that are experienced by small market teams.

How Small Market Teams Are Responding

While these rules are ultimately inadequate for solving the payroll and winning issue in baseball, there is some room for small market clubs to take advantage of their situation and punch above their weight. So how are some teams counteracting the disparities in the league in terms of payroll and success? Small market teams are forced to innovate due to their circumstances, and as a result, they have become thought leaders for the game of baseball.

For example, the Oakland A’s are well known for innovating through “moneyball,” where the franchise used data-driven insights to evaluate talent. The A’s identified an inefficiency in the market, and capitalized by using objective analyses in a game that was being judged by the eye test. However, while most people view the moneyball strategy as purely driven by sabermetrics, the A’s plan was most effective due to the franchise’s ability to save money. The A’s could save plenty of money on scouting by using their computer algorithms, and they were able to find bargain contracts on offense by acquiring players based on their advanced statistics. However, in today’s game, the richer teams have picked up on the A’s strategy, and have built their own analytics departments to remove the A’s competitive advantage. Regardless, the A’s still engage in a more current version of “moneyball,” where they have discovered that veteran players are undervalued by the rest of the league. As a result, the A’s continue to find creative ways to generate value out of limited resources, with the signing of veterans like Mike Fiers and the savvy acquisitions of experienced players such as Khris Davis to build around their strong young core of Matt Chapman, Matt Olson, and Sean Manaea.

Another example of a small market team maneuvering the system is the Tampa Bay Rays. The Rays have also followed in the A’s philosophy of using analytics, by introducing the “opener” in baseball, where a relief pitcher starts, a long man eats the middle innings, and the bullpen closes the game. This strategy is effective when considering a pitcher’s statistical decline after the second time they face a lineup, and saves money when taking into account the premium that the baseball market places on starting pitching. Eventually we should see the starting pitching role eliminated, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the Rays are the leaders in this movement. The Rays have also engaged in frequent asset shuffling, as a majority of their current players were acquired through trade. Most notably, the Rays acquired Tyler Glasnow and Austin Meadows for Chris Archer, a classic example of trading an expensive star for valuable young pieces with years of team control left of their contracts.

Third, small market teams have started a trend of signing young players to long-term contract extensions, as the Rays did with Blake Snell, the White Sox with Eloy Jiménez, and the Braves with Ronald Acuña Jr. These contracts have given both the team and the players financial security, by having a guaranteed figure that avoids the fluctuation and uncertainty of the contract renewal and salary arbitration processes. However, the real benefit of these contracts and why they are innovative is that the Rays were able to extend Blake Snell to his seventh year of service time, and the Braves will get even more years of service from Ronald Acuña Jr. before he demands a large payday in free agency. By postponing a player’s eligibility for free agency, and removing the volatility of salary arbitration, teams are able to plan and have long-term savings as a result of these contract extensions given to young players.

While these three strategies are effective, they still have their limitations. In terms of analytics, big market teams’ front offices are becoming smarter, and are able to spend more in order to outpace small market teams in terms of their infrastructure. Second, the frequent trading and movement of assets creates uncertainty for players, which decreases morale and removes the sense of a long-term commitment that players want out of their teams. Lastly, while extending young players to long-term contracts is healthy for both sides, superagents such as Scott Boras will eventually start to tell their players to gamble on themselves and maximize their paydays after their six initial years of service time.

How Can The MLB Fix This Issue?

So, with these shortcomings in mind, how can the MLB help out small market teams to fix the issues with large spending and winning?

First, to counteract large market teams poaching the young, rising stars of small market teams, the MLB should consider putting a franchise tag in place. A “franchise tag” is a right for a team to have exclusivity to one player on their roster. When a player is franchise-tagged by a team, that player is forced to play under a one year contract with the team, and the salary is set by the league. In the NFL, the franchise tag is not very well supported by the players, and has led to holdouts and stalled contract negotiations in the league. However, I think the MLB can avoid these issues if they are creative in how they structure the contract from the franchise tag. Similar to the qualifying offer, the MLB can have the value of the franchise tag be a one year contract worth the average value of the top 30 contracts in the league, which would be somewhere in the low to mid 20 million per year range. If the MLBPA does not find this lucrative, then the MLB can get creative and suggest a subsidy for these contracts, where players can receive additional money from the league that would come from MLB teams pitching in to a “franchise pool.” If this does not satisfy the players, then the MLB can propose to have the franchise tag carry deferred money, where the value of the contract is for one year, but a player receives additional money in subsequent seasons after they are franchise-tagged. It is important for the league that its star players are spread out in large and small markets, both for revenue and competition purposes. Therefore, the MLB should consider proposing a franchise tag so teams, small and large alike, can keep their stars.

Second, the MLB can strengthen its luxury tax penalty to prevent big market teams from spending insane amounts of money on their payroll. The current luxury tax system only taxes overages on payroll, so why not just apply the tax percentage on the entirety of a team’s payroll? Under the current system, teams still have a marginal benefit if they exceed the threshold by a small amount, so even after the implementation of the current luxury tax, we still see big market clubs spending over the threshold and accepting the tax. Additionally, under the current rules, the penalty of the tax is redistributed to all 30 teams, but what if the MLB has the tax be paid to the clubs to whom large spending hurts the most? The MLB should propose that the luxury tax revenue (from the penalty) would go to the bottom third of the league in terms of franchise value, because those are the teams who have the least resources, and therefore experience the most burden when a richer team spends large amounts on their payroll. The MLB and MLBPA will probably never come to an agreement on a hard salary cap, but a harsher luxury tax is more reasonable, and a key step towards clamping down on big market clubs spending to the max on their players.

Third, and a topic that is being currently discussed, is a playoff format redesign for the MLB. Under the current system, only five teams per league make it to the playoffs, and since the wild card game is only a one-game playoff, only three teams (the division winners) are actually guaranteed a playoff series. Therefore, if a team is looking at which direction they want to take their franchise, and they determine that it will be difficult to win their division, why would a team go “all in” for a chance at a one-game playoff? As a result, many teams in the MLB are tanking, and if most teams are tanking, there is no real advantage to rebuilding, since you are not at a point where you are “zigging” when everyone else is “zagging.” Furthermore, let’s say you are the Tampa Bay Rays, and are stuck in a division where the Red Sox and Yankees are large market teams and the Blue Jays and Orioles are typically middle-of-the-road in terms of payroll. How will you ever be a sustainable challenger for the playoffs when you are at a clear disadvantage in payroll every year in your division?

The MLB needs to expand the playoff field, and here’s what they should suggest. The top two teams in each division make it to the playoffs, along with two wild cards, and are seeded first according to whether they won their division, and then according to regular season record. Yes, you may say that more than half of the league would make the playoffs, but this is already a reality in both the NBA and NHL. The real intent behind expanding the playoff field is to give teams an incentive to win, because a playoff appearance and a deep run would be more likely.

In addition, the playoffs should not be one or three-game “series,” but five-games for the quarterfinals, and seven games for the AL/NL semifinals, championship series, and then world series. This makes sense because if we allow more teams into the playoffs, we would want to remove the “luck” factor that would provide less importance to playoff seeding. Therefore, having longer playoff series would lessen the chance for a lucky upset, especially after a hard-fought 162 game regular season. If the MLB were to change their playoff format and expand the playoff field, they would experience more success in competitive balance and would give small market teams a better chance at the spotlight.

Conclusion

The issue of money in baseball has been debated for ages, but it is time for the MLB to realize that the inequalities between small and large market clubs are perpetuating competitive imbalance in the league. Baseball is a sport that is on the decline in terms of popularity in America, and if the league can empower small market teams, then they will rejuvenate baseball markets across the country and grow the game. With the collective bargaining agreement expiring in 2021, the MLB and MLBPA have a significant opportunity to make progress towards improving the league’s structure. However, while the changes that we are most likely to see will involve changes to the rules on the field, we can only hope that the league and players association recognize the institutional issues that are also responsible for the decline in excitement on the field.

[…] salary cap to limit the actions of teams based in larger markets. Instead, the MLB utilizes a luxury tax that ultimately does little to keep payrolls equal and only applies to money that teams spend over […]

The Atlanta Braves won the WS with the 11th highest payroll and the Tampa Bay Rays, 5th from the bottom in spending, had the best record in the American League. Maybe it’s how you spend your money, not just how much you spend.

Bob, you can point to any individual anecdotal data point that doesn’t agree with the premise, and argue this “disproves” the trend. That is why they analyzed 20 years of data. Of course there are outliers that beat the odds. The premise of the statistical portion of the article is that 58 percent of seasonal outcomes can be predicted within a rank or two, just from looking at comparative payrolls. That is very significant, and is not undermined or disproven by the fact that the Rays have had a little success recently.