Poor mental health is an open secret at universities like Georgetown, and the trend is only getting worse. A 2018 national survey found that more than 41 percent of students reported feeling “so depressed that it was difficult to function” at some point in the previous year. Students experience higher levels of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and academic stress each year, and universities have struggled to meet students’ rising demand for mental health support and services.

Although the issue is not unique to any one university, Georgetown’s challenging curriculum and competitive extracurricular scene have been cited as causes of the poor mental health climate on campus. For students seeking mental health care, common starting points are Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) or Health Education Services (HES). Other resources include residential assistants, who receive training on mental health resources, peer leaders, or any number of student organizations dedicated to issues of mental health, such as Active Minds, Project Lighthouse and Actively Moving Forward.

Where to get help

The director of CAPS, Georgetown’s primary mental health care provider, Dr. Philip Meilman recognized the need for robust mental health services on college campuses. “Universities across the nation have been overwhelmed with requests for services; the demand has skyrocketed in recent years due to societal factors, social media, national unrest, the pandemic, and generational issues,” he wrote in an email to the Voice. Meilman also wrote that Georgetown’s offerings are consistent with other institutions across the country, in his experience.

Students seeking help can walk into the CAPS office on the ground floor of Darnall Hall, or call the office number for virtual appointments. Students can be seen the same day they seek help, according to the CAPS website. This initial consultation is a short appointment to evaluate the necessary treatment for any individual’s case before the student is referred to a clinician or other appropriate campus resource. Individual therapy sessions cost $10 each for a psychologist and $15 for psychiatrists. Students are able to schedule a limited number of visits before CAPS refers them off-campus for longer-term care, if necessary—CAPS rarely sees a student for longer than two semesters. According to CAPS, the short-term care model enables them to meet the high demand for mental health services and is standard at universities.

CAPS also plans to transition to a new after-hours phone service in case of mental health emergencies where students need help outside of weekdays from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. EST. CAPS clinicians will then follow up with students who use the after-hours service after being briefed by the service’s behavioral health nurses.

CAPS also offers workshops for students throughout the year and group therapy sessions, which are free of charge. “In many cases, group approaches are the treatment of choice for students and the most effective,” Meilman wrote. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, CAPS is also waiving their usual fee-for-service charges.

HES clinicians also work in tandem with CAPS to provide student care, though their staff focuses more on sexual assault and misconduct response, sexual health, substance abuse, and eating disorders. On campus, the HES office is located at 101 Poulton Hall.

Student advocacy

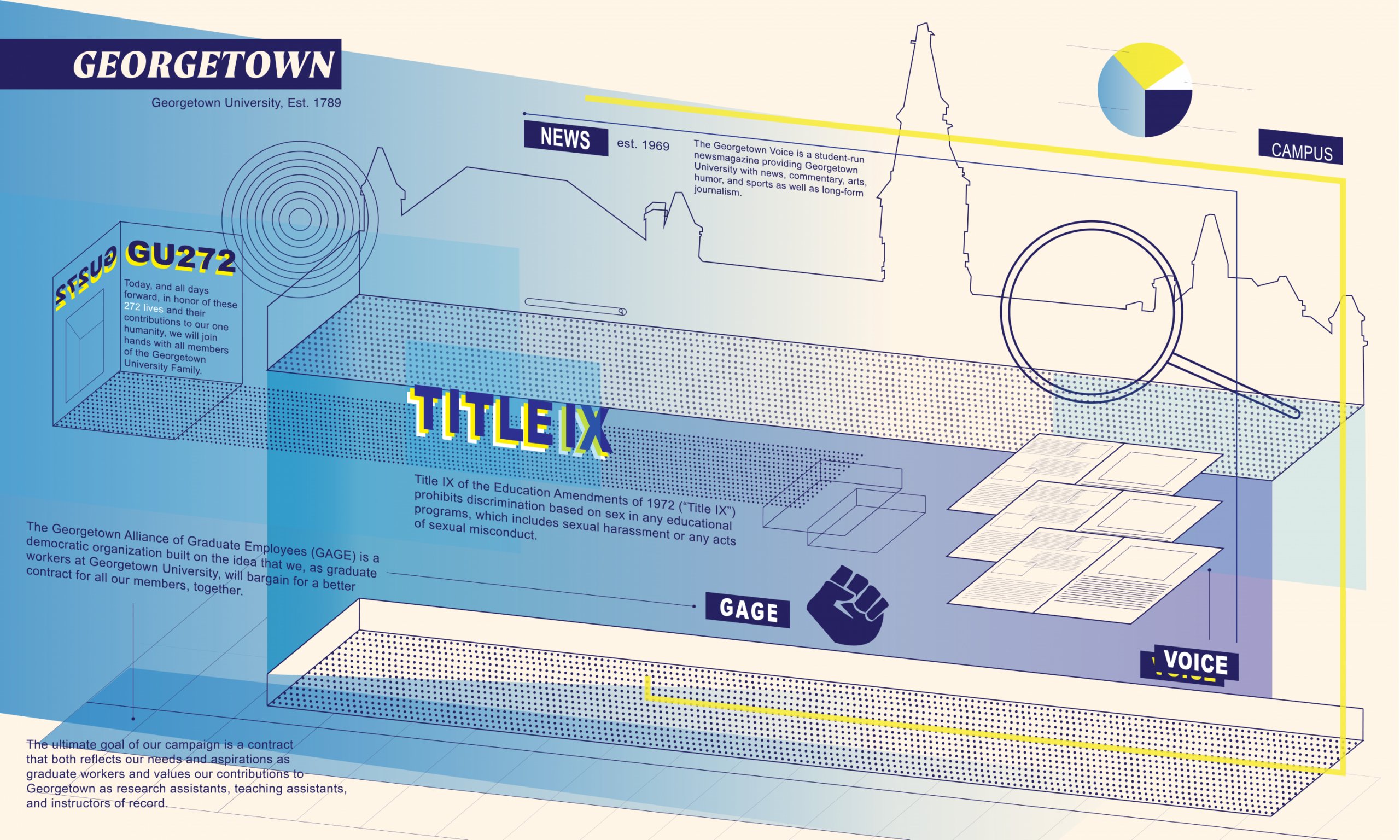

Many of the university mental health resources are not at the level students desire, leading to activism around the issue. GUSA, the Black Survivors Coalition, and a number of student clubs have advocated for an expansion of CAPS services and support, greater representation of communities of color and LGBTQ individuals among clinical staff, and a solution for students who require long-term care.

One university administrator responsible for aiding students in their efforts to make these changes is the assistant vice president for student health. Until recently, the post was occupied by Dr. Vince WinklerPrins, whom students described as a supporter of mental health initiatives. With that post now empty, student leaders lack a consistent supporter among the administration as well as a faculty advisor for some mental health clubs.

One major concern for students and GUSA’s mental health policy team is the limited staff at CAPS and the difficulty of booking appointments. When Pat Walsh (SFS’21) was the mental health policy chair, CAPS altered its walk-in policy to be able to evaluate students the same day. Greater accessibility only increased the demand for counseling services, as Walsh said, “CAPS felt under-resourced: it felt like it was always busy, and people were having trouble booking follow-up appointments.”

According to the executive summary of the CAPS 2017-18 annual report, student visits have increased every year since 2012. Even with hiring some additional staff, there was still only one counselor per every 1,040 students in the 2017-18 academic year. Many of those staffing the CAPS office are not full-time hires—some counselors split their time at other Georgetown campuses, and some are embedded part-time with the Georgetown Scholars Program (GSP), the Center for Multicultural Equity and Access (CMEA) or the Center for Social Justice (CSJ).

In addition to limited staff, CAPS has also been criticized for a lack of minority community representation. In response to demands of the Black Survivors Coalition, the office arranged contracts with a number of community mental health providers who focus on serving marginalized communities and who have experience with incidents of racial trauma. These services, though free of charge, have not yet been extended beyond Dec. 31, 2020, and are not seen as a permanent solution.

While the short-term care model may be consistent with other universities, it also leads students to make troubling choices about their mental health, according to Walsh. “There were folks who did not want to go to CAPS because there were concerns that they didn’t want to spend their limited visits at CAPS on this,” he said.

Long wait times of weeks to months and no easily-accessible long-term care means students sometimes wait for their situations to get worse before they seek help, according to Walsh. Sonya Hu (COL ’22), current GUSA mental health policy chair, described the appointment limit as “problematic for students who have a trauma to work with or need that long-term care, and especially first-gen and low-income students who haven’t had a chance to explore their mental health before this.”

In response, former mental health policy chair Kenna Chic (SFS ’20) pushed for the creation of a mental health stipend to cover the cost of off-campus care. Successive mental health policy teams sought to expand the stipend and shore up its source of funding.

Another sticking point for student advocates has been a nebulous medical leave of absence (MLOA) process. “There is a good deal of misunderstanding about medical leaves of absence for mental health reasons,” Meilman admitted. “The main purpose is to preserve a student’s academic record when mental health concerns are getting in the way of learning.”

Medical leaves are also highly individualized, as students consult their deans and counselors, so there is difficulty in codifying an easy process that fits everyone. Hu said that from the student perspective, “The problem with medical leave is that we don’t know a ton about it. So the focus of our work in medical leave is to develop a comprehensive understanding of what it looks like.”

Asked to describe an ideal mental health climate, Walsh said, “I think a dream world would be a larger CAPS office. Expanding that would be huge because they need more clinicians, more clinicians with diverse experiences, so that long-term care can be there.” Additionally, he believes an expansion of case management resources would help high-risk students, and proactive outreach would limit the number of students who end up falling into that category.

The main obstacle to proper care for students, according to student leaders, is not CAPS itself but an unwillingness on the university’s part to commit the necessary resources.

Walsh noted that CAPS clinicians could make much greater profit in private practice, but many staff members chose this work because they wanted to help students. “There are those in CAPS who are genuinely trying, and those who are doing what they can to support students; they just don’t have the resources from the university to do it,” he said. “The university hasn’t given the institutional tools and support to show that it’s serious about mental health.”

While Walsh has been encouraged by the advocacy and policy efforts of student leaders, he said it is frustrating to see the burden of fighting for better care placed on students.

Student mental health fund

In early 2018, the student mental health fund began its pilot program to address the costs of long-term care for students referred to off-campus counselors. GUSA fundraising and an anonymous donation of $10,000 provided the initial seed money for the stipend, and $15,000 in annual funding now comes from the university’s Division of Student Affairs.

The work to create a stipend began a year earlier with Chic, who realized the recurring high cost of D.C. mental health care prohibited some students from seeking the ongoing help they needed. In particular, “a lot of students of color come from backgrounds where the family may not be as open to talking about mental health,” she said. While GSP provides some emergency medical funding to low-income students, there was no widely-available way to cover the costs of accessing mental health services off-campus.

Years of data show an ever-increasing number of students seeking mental health care, so according to Chic, “The university knew that was something they would have to face.” After numerous experiences of peers taking medical leaves or not getting adequate care, she recognized how better access to services could prevent more severe situations before they happen. “If students were able to access care before they reached a breaking point, then perhaps these crisis situations wouldn’t play out and affect the students’ lives the way they do,” she said.

With guidance and support from Meilman and WinklerPrins, Chic proposed the stipend in GUSA and drew the backing of the Office of Student Affairs. Students began raising the initial money for the fund before an anonymous donor and eventually, the university added their support as well. Now supported by the Division of Student Affairs, a committee of staff members review applications to the fund and disburse money if the application is approved. Students must be referred to an off-campus psychologist and be full-time Georgetown students who are not part of GSP, which has their own funding mechanism.

Even so, Chic says the most sustainable future for the stipend would be an endowment. The university currently funds the stipend on an annual basis.. There is no long-term guarantee of support, however, and the $15,000 annual contribution barely covers 70 off-campus visits (the average cost of individual therapy in D.C. is $215 per hour). Furthermore, students may only receive up to $500 if their application is accepted. The fund also withholds a portion of the disbursement until the student has submitted two clinician visit acknowledgment statements from their provider, at least one month apart.

Recalling his own efforts to ensure a future for the fund, Walsh said, “There was some hesitancy last year among administrators that we’d be institutionalizing a stopgap measure. To which we responded that the university is not prioritizing this, so it’s all we can do right now until the university really expands CAPS and HES.”

Student-run resources

Active Minds

The Georgetown chapter of Active Minds is a branch of the national D.C.-based organization which seeks to promote positive mental health and wellness among high school and college students. The chapter’s president, Kaitlyn Reynolds (COL’ 21) said, “We try to find creative ways for the student body to engage in conversation.”

On campus, Active Minds organizes several forms of informative programming, including regular dinner discussions with guided themes, as well as documentary screenings regarding mental health, tabling with information about appropriate resources, and collaborations with other student organizations.

“Most students who come to us don’t know where to start,” Reynolds said. “Georgetown has this culture of striving for perfection rather than for personal excellence, and students feel like they don’t know who they can talk to about this.” The organization, though not able to offer clinical advice or evaluations, also works closely with CAPS and HES to connect students with more professional resources.

According to Reynolds, many of the issues that students face at a top-tier university like Georgetown relate to performance, anxiety, depression, and impostor syndrome and similar doubts. Talking to peer groups like Active Minds is often the least intimidating first step in having conversations about one’s mental health and seeking appropriate care.

Project Lighthouse

Another peer organization, Project Lighthouse focuses primarily on offering anonymous peer support through an online chat service available to all students. The organization began in 2016 with a short beta-test, after which it took off and became embedded as a mental health resource on campus.

The club’s peer supporters are anonymous and the chat service collects no data on its users. According to president Becky Twaalfhoven (SFS’ 21), this allows students to feel more comfortable sharing issues they may not want to speak about openly. “There’s still a lot of stigma around mental health, and even just walking into CAPS can feel intimidating,” she said. “Talking to someone your age feels more accessible, and peer support has been shown to be a worthwhile resource.”

Walsh elaborated, “It’s sometimes hard to feel like you can open up without the sense that people are judging you for it, or that you’re inadequate compared to people who don’t open up as much.” The chat line is open nightly from 7 p.m. to 1 a.m. during the semester, which gives students a resource even when CAPS is closed.

Upon its launch, CAPS and HES advised Project Lighthouse and helped to build its training curriculum. Students interested in becoming peer supporters go through 20 to 25 hours of training during the semester, participating in learning sessions and modeling scenarios to learn how to respond to specific situations.

me, myself & mInd

A collaboration between GUSA, Project Lighthouse and Active Minds, the website “me, myself and mInd” seeks to provide a space for students to share stories and destigmatize talking about mental health, in addition to providing information about campus resources.

“In order to get the freshmen class involved, we established a spreadsheet where students—especially freshmen—were encouraged to submit personal accounts of their mental health journey and/or mental health resources either on or off of campus,” Reynolds wrote in an email to the Voice.

The website also emphasizes the prevalence of mental health issues among LGBTQ+ students and students of color, who are also less likely to seek help than their peers. In an effort to address these disparities, the website lists dozens of community-specific resources students can access.

Virtual care

The transition to virtual learning has added more complications to the mental health services the university offers, including a heightened need for mental health care despite greater difficulty reaching the majority of off-campus students.

CAPS has already waived fees for its services, and Meilman wrote, “Where needed and appropriate we conduct counseling, psychotherapy, and psychiatry visits virtually. We have found video conferencing to be just as effective in most instances as in-person services.”

Clinicians must be licensed in the states in which they practice, so CAPS cannot offer services beyond consultations to students outside the DMV area unless their state licensing board has made provisions for telehealth visits.

“Stay-at-home orders and distancing are difficult for people with mental health issues, and they’re also cut off from their support system,” Hu said, noting that CAPS is only able to provide psychotherapy in D.C., Maryland, Virginia, Florida, New York and Colorado due to the licensing of their clinicians. Seven additional states have waived licensing restrictions for telehealth visits, though according to Hu, these provisions are due to expire shortly.

To address the need, Georgetown has partnered with online services HealthiestYou and BetterHelp, which provide virtual counseling visits and fall under the student health insurance plan.

Student organizations are also reevaluating their offerings in light of a dispersed student body. Twaalfhoven expects Project Lighthouse to adapt well to the new climate. As their services are already online-based, and students are not required to be licensed to provide peer support, her main concern is spreading the word and getting information out. “We’ll have to update all our resources to reflect the fact that they’re virtual,” she added, as well as “continuing to be sensitive that everyone is in a different situation and re-emphasizing that. And for incoming students, they probably are incredibly overwhelmed.”

Active Minds is also adapting its events to fit a virtual environment. Reynolds wrote in an email to the Voice, “Our biggest concern is trying to find a way to allow the students to feel comfortable enough to open up about their mental health struggles while simultaneously being in a potentially triggering home environment.”

“This is not the year anyone was expecting. It will be very hard to instill that community of care in each other because everyone is so far apart,” Walsh said. Yet he remains hopeful that student organizations will find a way to care for the Georgetown community. “I really hope that the semester can shine a renewed light on how our mental health services are not equipped for what students need right now,” he said. “Students will be the ones who take up the responsibility of caring for each other.”