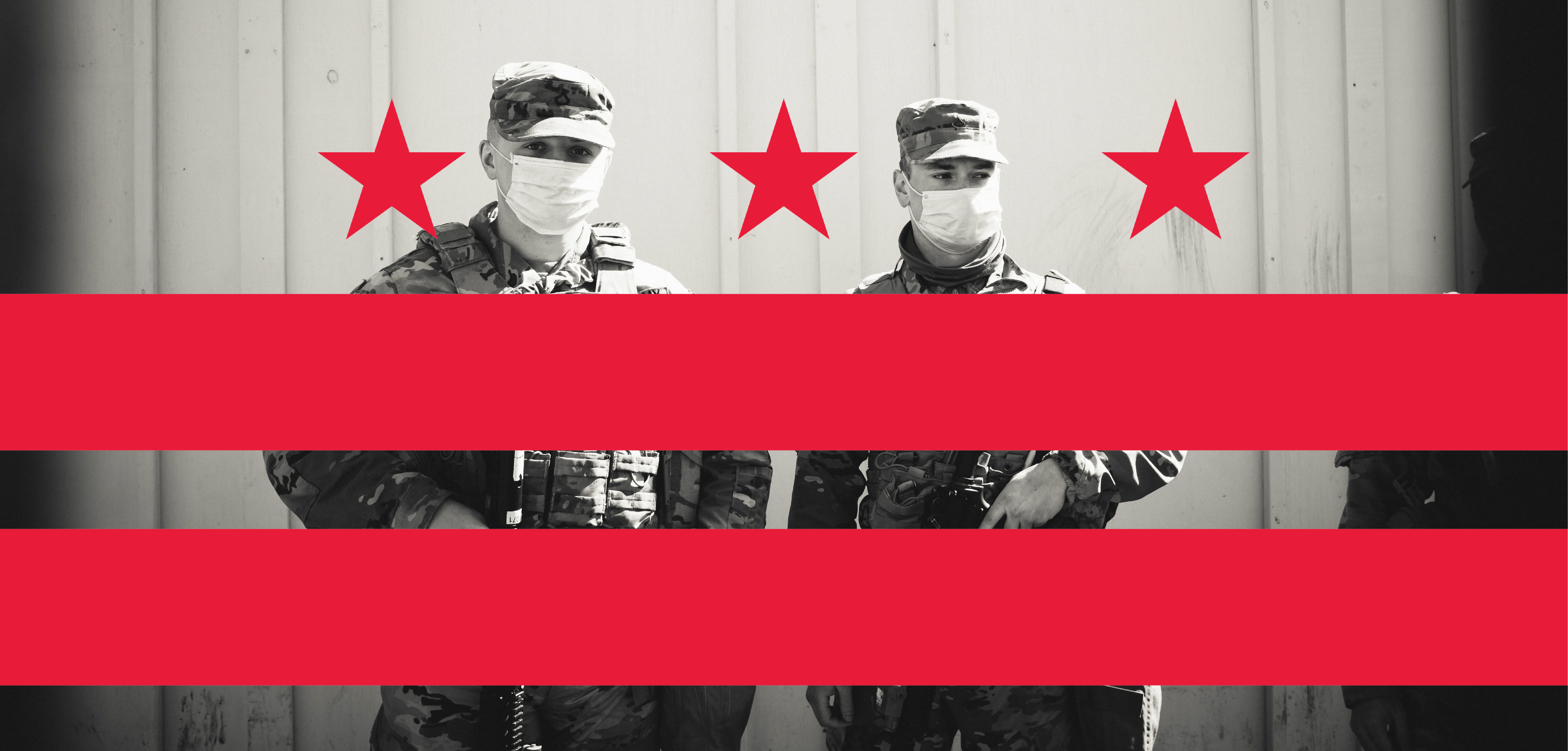

Steel barbs still rest atop the barrier that now surrounds the People’s House. Armored trucks still crowd the streets. Even as 10 weeks have passed since pro-Trump white supremacists raided the Capitol on Jan. 6, the lingering presence of armored vehicles and stationed troops paints the portrait of a city reeling in the aftermath of insurrection. The shattered glass may be gone, and the attackers departed, but “Fortress D.C.” is here to stay.

Already a city with one of the nation’s largest per capita police presences, “Fortress D.C.” is subject to historic levels of military presence and hospitality closures. Now, residents have been forced to withstand growing federal militarization as officials grapple with the intelligence and security failures on display in January. Multiple extensions to the National Guard’s stay in the city, as well as recommendations of more permanent physical security measures at the Capitol, have some D.C. residents and lawmakers concerned about establishing a new precedent of mass surveillance and military overreach into civil affairs.

“The attacks on Capitol Hill took place more than two months ago and instead of fixing places on the Capitol where people have barricaded and improving the training of Capitol Police, we are still locking the city down,” Rowlie Flores (COL ’22), a student living on campus, wrote in an email to the Voice. “This is not the way to go.”

After they were mobilized on the day of the attack, the number of National Guardsmen in Washington swelled to 25,000 by the time of President Joe Biden’s inauguration. Their ranks decreased to around 5,000 in the weeks afterward, but troops remain active in the city as a security measure, meant to dissuade any potentially emboldened far-right extremists. Amid continued fears of violence, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin approved keeping more than 2,000 guardsmen in the city through May 23, which will be four months after Biden was sworn into office. The long-term National Guard deployment and Capitol fortifications are costing American taxpayers about $2 million every week, in addition to tens of millions of dollars spent responding to the Jan. 6 assault.

Washington, D.C. is no stranger to heavy police presence. The city already has the 10th-largest funding allocation on police apartments, with the FY 2021 police budget totaling $544 million, among the 50 most populous U.S. cities. The Black Lives Matter protests last summer highlighted the unequal ramifications of the presence of law enforcement and criminal justice systems for different racial groups. In the District, an ACLU study found Black individuals make up a disproportionate percentage of people arrested, comprising 47 percent of the city’s population but 86 percent of its arrests. The disparities held up across neighborhoods, including those with the highest concentration of white residents. Furthermore, Black residents accounted for more than three-quarters of traffic stops, which can signal racial discrimination since officers have no way of knowing whether the suspect possesses a valid license before taking action, according to the ACLU.

“Seeing this in the city has been quite alarming, as a person of color, especially as police brutality remains to be a serious issue in the United States,” Flores added of the increased law enforcement presence.

A personnel increase is just one of the many changes made to the Capitol grounds and city at large in the January attack’s wake. The inauguration saw 13 Metro stations close to discourage in-person attendance, and at least 16 arrests were made in the days before. Metal detectors were installed at the House chamber’s entrance to prevent lawmakers carrying firearms onto the floor. Concerns about the possibility of an insider attack kickstarted a major FBI effort to identify and root out radicalized guardsmen, 12 of whom were dismissed. More recently, Capitol Police suspended an officer pending investigation for having antisemitic reading material near his workplace.

Perhaps most visible among these recent alterations, however, is the barrier. Razor wire-topped fencing encloses several blocks around the Capitol building and roughly 60 acres of grounds. Armed guardsmen patrol the entire perimeter while D.C. residents and visitors take pictures and find detours around the militarized zone. Believing the harsh construction to be at odds with the building’s history as a symbol for democratic, publicly-accessible governance, the barrier has been a point of contention for many D.C. lawmakers and residents.

“I am completely against the fencing and have spoken out against it,” Phil Mendelson, chair of the D.C. Council, wrote in an email to the Voice. “A democratic society is an open society. All these fences are antithetical to democracy and absolutely against the ideals in which our republic was founded.”

A spokesperson for the councilmember added, “Constituents have continually voiced opposition to the capitol security measures and have referred to it as a ‘militarization of their community.’”

District residents organized a protest against the Capitol’s militarization on March 13. Demonstrators were encouraged to bring dogs, kids, bikes, picnics, and other outdoor activities made more difficult by the presence of security forces. Separate from leisure, community members also pointed out how the fence disrupted essential roads for first responders. Sidewalk and road closings around the Capitol complex have made transportation difficult for residents and could force detours even for emergency vehicles. “We will meet at 2nd St SE and East Capitol Street, spread out along the fence, and do the kinds of things we’d rather enjoy doing on the other side,” the announcement read.

The Capitol Hill protestors took to social media to document their positions and D.C.’s congressional delegate, Eleanor Holmes Norton, joined in opposition to the fortifications.

“More than most Americans, those of us in DC who live close to the Capitol feel fenced out of our own Capitol,” she wrote in a post. Norton has made the case for taking down the barrier in multiple media outlets.

Norton later shared a small measure of progress toward scaling back the fence. According to a March 15 security memo sent to lawmakers, the Capitol Police intend to reduce the size of the enclosure. On March 19, the acting House sergeant-at-arms announced plans to remove the outermost cordon of fencing from the Capitol grounds over the weekend, reopening sections of traffic by the following week. Some razor wire was removed selectively from the inner fencing, but the National Guard presence and barriers will remain.

Some D.C. residents on social media applauded the first steps toward opening access to the Hill, but others expressed concern about making sidewalks accessible to pedestrians rather than just opening roads for vehicles. One user remained skeptical, tweeting, “I really hope this is because of a change in security status rather than a desire for better optics.”

Continuation of the heightened security presence has also drawn the ire of lawmakers from both major parties. Some Republican congressmen and senators lay the blame at Democrats’ feet, accusing them of political motivations for keeping security measures in place, such as using the physical blight to emphasize the memory of former President Donald Trump’s involvement in the riot. Democratic legislators, on the other hand, assert they are eager to see the fencing disappear but will follow the guidelines of security officials.

Even with the fence taken down, long term changes to Capitol security could be in store, fundamentally changing the way citizens interact with the Capitol complex. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) commissioned a security review, which laid the issue out frankly: “In securing the Capitol grounds, competing desires for maximum public access and guaranteed security create a situation where neither goal is achieved.”

The review recommended an expansion of the Capitol Police force and its intelligence capabilities, permanent mobile fencing on site, and background checks for congressional identity card holders. Paying special attention to the overstretched Capitol Police, who logged a collective 720,000 hours of overtime last fiscal year, the report specifically urged an increase of nearly 900 employees to the existing 2,300-man force. Further suggestions included mounted units, filling posts in K-9 units, and assuring the security of lawmakers outside Capitol grounds, bringing security into the city at large.

“In light of recent events, I can unequivocally say that vast improvements to the physical security infrastructure must be made to include permanent fencing, and the availability of ready, back-up forces in close proximity to the Capitol,” acting Capitol Police Chief Yogananda Pittman said in a statement following the Jan. 6 attack and resignation of her predecessor.

Increased security and militarization of the District mirror past catalysts for increased fortifications around national landmarks. The Capitol has a long history of attempted attacks, though few on the scale of the Jan. 6 insurrection. Other major national security events, such as 9/11 and lone shooters attacking the Capitol, provided an impetus for federal agencies to build up a robust intelligence and security network that contributed to making D.C. one of the most heavily-policed cities in the country.

The Sept. 11 attacks of 2001 in particular provoked an increase in fortifications on Capitol grounds, including vehicle checkpoints and road closures. A visitor center at the Capitol empowered security to screen members of the public farther from the building itself. Magnetometers installed throughout the complex improved oversight, and updated surveillance systems kept close watch on citizens.

This stringent security was not on display earlier this year when the threat to national security came from primarily white, pro-Trump extremists, including veterans and off-duty law enforcement officers. Lawmakers have since criticized the FBI for downplaying the seriousness of white domestic terrorism, even as intelligence agencies improve acknowledgment of the threat of white supremacy: Last year, the FBI elevated its threat assessment of racially-motivated violent extremism.

When public outcry condemned some officers for seeming to assist the rioters or taking selfies with them, some Black colleagues were unsurprised, as the force has faced hundreds of suits from Black officers alleging racial discrimination in the past 20 years. Multiple Black former officers on the Capitol Police force spoke up about a legacy of racial discrimination in the department, which leads to lenient responses to security threats from white individuals. One retired officer, in an interview with ProPublica, said the dismissal of racial discrimination and hate in the department was partly responsible for the breakdown in the police response to white supremacist rioters earlier this year.

A second factor was critical failures in federal law enforcement response to the attack that claimed the lives of five people and injured almost 140 law enforcement officers.

Of the 54 National Guard divisions for each U.S. state, Puerto Rico, Guam, the Virgin Islands, and D.C., the D.C. National Guard is an outlier. A section of the D.C. code written before the District of Columbia Home Rule Act of 1973, which gave the city the power to elect a mayor and council, states that the U.S. president is the commander in chief of the D.C. militia. In practice, this means the District’s National Guard requires authorization from the president or approved delegates, such as the Secretaries of the Army and Air Force, before being deployed.

D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser’s lack of authority over the city Guard caused a delay in deploying forces against the insurrectionists, as the request had to travel along a chain of command within the Department of Defense. Without D.C. statehood or full home rule, the city government is unable to call on the District’s National Guard for assistance in other emergency situations, including public health crises or natural disasters.

The D.C. Guard’s vague federal-militia status caused outcry in Trump’s presidency as well, when he mobilized the Guard in 2020 to quell demonstrations against police brutality in the city as part of a larger national crackdown primarily directed at Black protestors. Normally, such actions would require congressional authorization, but D.C.’s unusual status allowed for a de facto federalization of the city’s Guard and for the contingents from 11 other states to be deployed on District land without oversight.

There were signs of earlier failures too. Despite warnings of possible extremist violence leading up to Jan. 6, former Capitol Police Chief Steven Sund, who resigned 10 days later, did nothing to bolster preparations.

In hearings and public appearances following the insurrection, intelligence and law enforcement officials were keen to pass the blame. The sergeants-at-arms for both the House and Senate resigned along with Sund, and all three pointed to a lack of information from federal officials as the reason for not requesting National Guard backup before the day unfolded. Countering that narrative, Wray emphasized an FBI field office report from the day before warning of violence in the city on Jan. 6, though Sund argued the information never reached the proper security officials.

Leading up to the Jan. 6 demonstrations, the Pentagon restricted the National Guard to very specific functions, such as handling traffic. Guardsmen were not allowed to arm themselves with ammunition or riot gear, share equipment with law enforcement, or respond to rioters unless absolutely necessary before the riot unfolded. According to numerous defense officials and Mayor Bowser, reluctance about supposed bad optics surrounding sending armed militiamen to a government building further delayed the Pentagon’s decision to assist local law enforcement.

When guardsmen flooded into the District following the attack, officials failed to make proper arrangements for housing and public health. Media outlets reported thousands of troops sleeping in parking garages after vacating government buildings. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) responded to the news on Twitter, writing, “If this is true, it’s outrageous. I will get to the bottom of this.” In the days following the inauguration, the Guard reported 200 positive COVID-19 cases, with more troops in quarantine. Mass testing at the time revealed positivity rates upward of 10 and 15 percent in some units, far beyond the publicly-reported numbers.

In the months following Jan. 6, law enforcement officials have been preparing for potential continuing extremist violence. March 4 came and went without incident following conspiracy theories about an attempt to reinstate Trump as president, but worries persist about Biden’s upcoming address to a joint session of Congress.

“Jan. 6 was not an isolated event. The problem of domestic terrorism has been metastasizing across the country for a long time now, and it’s not going away anytime soon,” FBI Director Christopher Wray said in a testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Just as fencing, roadblocks, and armed guards at government buildings became part of the scenery in the post-9/11 world, residents and lawmakers alike worry that these new D.C. measures too will become normalized.

“Things that began as temporary sure have a habit of becoming permanent pretty fast in this town, and we can’t allow that to happen here,” D.C. Councilmember Charles Allen said in an interview with NPR. “It’s not a good look for democracy, but it’s also not the right solution for the security concerns,” Allen, who represents the Capitol Hill neighborhood, added.

Flores concurred, writing, “Quite frankly, I don’t think the Fortress is fixing the problem that led to the January 6 attacks. Instead, we are creating a city that has succumbed to a group of people who believes in QAnon conspiracies. This ‘fortress’ from my experience of being in the area has turned attractions as places to be avoided because of high militarization.”

The indeterminate length of National Guard deployment, rising costs of maintaining high security, and anxiety over future permanent measures that may curtail the liberties of D.C. residents have provoked unease at all levels of government and citizenry. These misgivings extend to those tasked with public safety themselves. One guardsman standing at a corner in the perimeter fence last month, when asked how long he had been stationed in the city, said, “Too long.” He shook his head, “Too long.”