The “Georgetown bubble” is very real—we say it all the time. We often admit that our university operates as its own little isolated community within a neighborhood that’s already secluded from the rest of the city. But for some Georgetown students, breaking this bubble may just mean commuting to an internship on the Hill, experiencing nightlife in Dupont, or walking to the National Mall. To better understand the city in which we live, we need to acknowledge our privilege, and the vast racial, socioeconomic, and health disparities—which are all deeply interconnected—that exist in the rest of D.C.

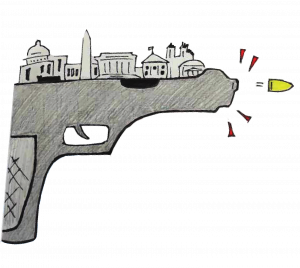

D.C. has one of the highest levels of income inequality in the country, something we may not all recognize from our comparatively privileged part of the city. The richest 20% of households in D.C. took home over half of the district’s total income in 2023, a predominantly white group that earned more than the bottom 80% combined. This wealth is disproportionately distributed throughout the city: those living in Northwest D.C., primarily in Wards 2, 3, and 4 (which includes the Georgetown neighborhood), have a net worth 65 times greater than those living east of the Anacostia River, namely in Wards 7 and 8.

These areas are home to some of D.C.’s poorest populations, and it’s no coincidence that its residents are predominantly Black. This is the result of a long history of racism and gentrification, driven by zoning policies and unaffordable housing, that has forced Black populations out of areas where they once thrived, including the Georgetown neighborhood. Wards 7 and 8 had the highest percentage of households living below the poverty line in 2024, at 23.85% each. No other ward surpassed 10%.

Despite its comparative affluence, we frequently complain that Georgetown lacks its own metro stop, making the neighborhood more inaccessible. It’s worth noting that Georgetown residents have supported this intentional choice for decades, many of whom felt threatened by the kinds of people that a metro stop might bring—a clear reflection of the same deep-seeded racist and elitist attitudes that fueled the neighborhood’s gentrification. While the complaint about the lack of a metro stop is valid, we often forget how lucky we are to have access to the things we need right within the neighborhood. We can choose to shop at Trader Joe’s, Safeway, or Whole Foods, all of which have a wide variety of healthy foods, are within a few blocks of each other, and are an easy walk from campus.

Other communities in D.C. are not as fortunate. Many areas, mainly those in Wards 7 and 8, suffer from a lack of full-service grocery stores and access to public transportation. They have only three full-service grocery stores in total; other wards have anywhere from nine to sixteen each. They also only have five metro stops to serve a population of over 147,000 residents, many without cars, further isolating them from resources—such as grocery stores—in the rest of the city. This “food apartheid” reflects a history of racism and discrimination, disproportionately hurting the area’s largely Black population.

We also tend to overlook the ease at which we can access healthcare. We’re only a short trip down O Street away from CVS, and live in immediate proximity to a highly ranked hospital. Meanwhile, Wards 7 and 8 are currently home to one hospital. That hospital, United Medical Center, which is also D.C.’s only public hospital, lacks the resources to adequately serve its community. In 2017, the D.C. Department of Health ordered it to close its labor and delivery unit after a series of preventable mistakes in treating patients, forcing expecting mothers to find care elsewhere ever since. This disparity extends to physician distribution as well: Ward 2, where Georgetown is located, had one full-time physician for every 262 patients as of 2018, compared to one for every 4,358 in Ward 7.

As a result, these communities face disproportionately higher rates of disease and health problems compared to the rest of the city. For instance, Wards 7 and 8 have the highest levels of adult obesity and preterm births in the district. HIV is another health concern disproportionately affecting Black residents concentrated in these areas. Life expectancy is on average 15 years lower than that of residents in other parts of the city—an alarming disparity. The health issues that stem from this limited availability and access to healthcare are only exacerbated by the lack of grocery stores and public transportation.

Georgetown’s student population is also not entirely reflective of the neighborhood’s overwhelmingly white and wealthy makeup—the issues faced in certain areas of D.C. may echo many students’ own personal experiences and upbringings. I don’t want to minimize the real struggles that many Georgetown students do face, and our complaints are often valid: living in Georgetown is absurdly expensive, access to public transport is limited, and the streets are lined with shops and restaurants that are often unaffordable for college students. Without forgetting this, it’s crucial that we reframe the way we see ourselves as a part of D.C., for we are truly in one of the city’s most privileged areas.

So, why should we care? Many of us may not wander outside the Georgetown neighborhood often, let alone find ourselves east of the Anacostia. These startling income, food, and healthcare disparities are easy enough to ignore in our day-to-day routines. Some of us probably don’t even realize that such inequalities exist (I certainly didn’t when I came here). But if we pride ourselves on living in D.C. and being a part of this community, we need to recognize what that really means. Understanding the various deep-rooted inequalities that persist in the city is crucial—not just because they exist, but because it challenges us to see beyond our immediate environment, take responsibility, and do what we can to build a more inclusive and equitable community.

With this in mind, we collectively need to recognize that going to Georgetown is not indicative of the harsh realities that many D.C. residents face. Let’s be honest, we’re all guilty of complaining about having to eat dinner at Leo’s on Saturday night—myself included—but recognize that this is a privilege. Educate yourself about local news, policies, and issues; be aware of D.C.’s problematic past, and how it continues to impact the city today. Make a conscious effort to step outside the Georgetown bubble and engage with the larger D.C. community.

It’s easy to get involved right from campus: the Center for Social Justice Research, Teaching, and Service supports a variety of student volunteer groups who tackle challenges such as food insecurity, healthcare access, homelessness, and other crucial issues within D.C. To see a different side of the city, instead of heading down M street to shop or get dinner, try supporting local small businesses instead, particularly those in less affluent areas. The scope and breadth of these issues can seem daunting and discouraging, so start with small concrete actions. To truly call D.C. home, we must take the time to really learn and care about the issues that persist beyond our neighborhood.