Content warning: This piece includes a quoted racial slur.

Entering McDonough Arena between 1972 and 1999, where Georgetown’s basketball team practiced, was a nearly impossible task.

“When you came into McDonough, everything was taped up—it was like Fort Knox. The windows were taped, the doors were taped, the doors were locked,” Joey Brown (CAS ’94), a former Hoya basketball guard, said.

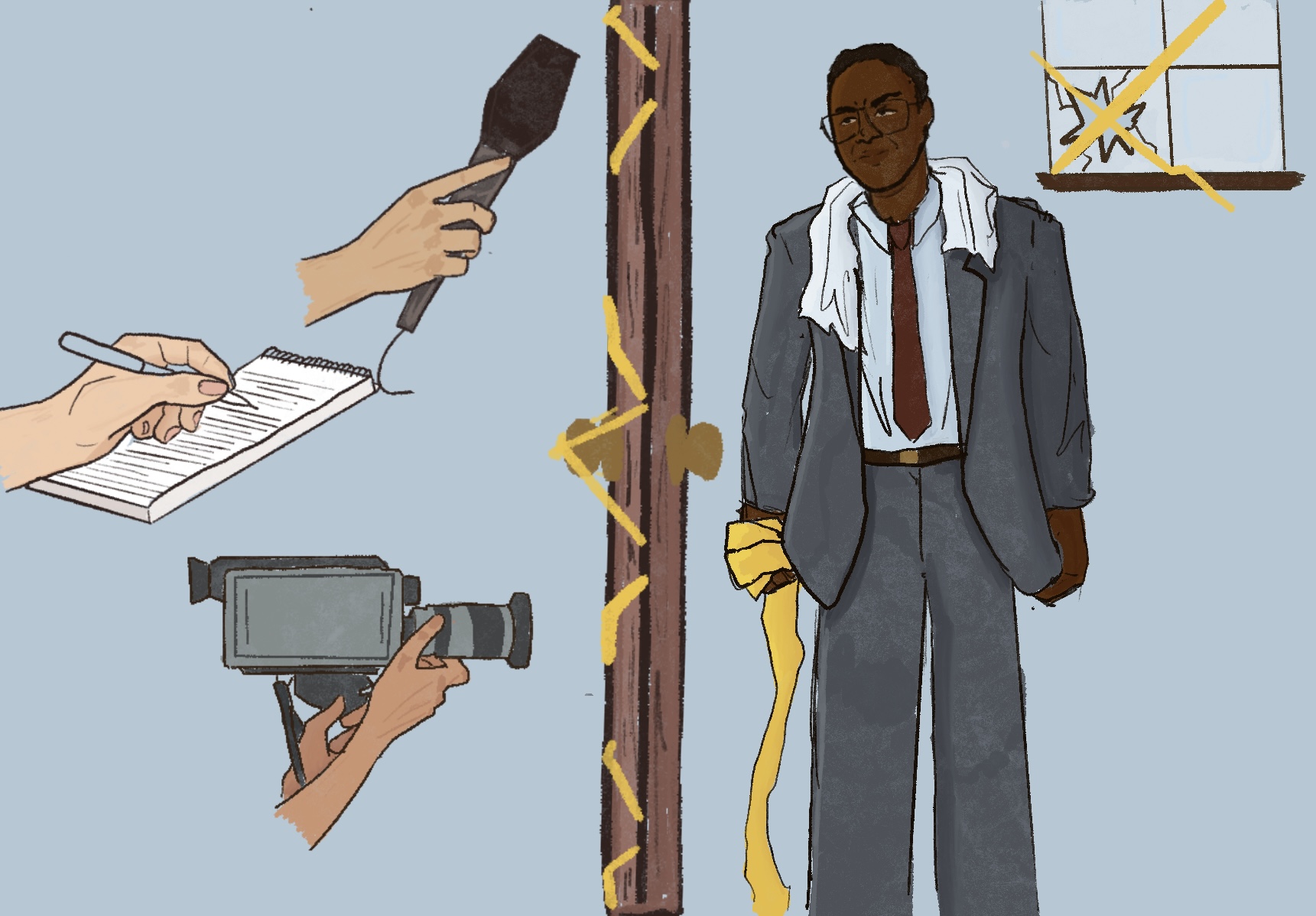

Inside, Coach John Thompson’s basketball teams ran sprints.

In the 27-year Thompson era, secrecy shrouded his national championship-winning basketball teams: how they operated off the court was a mystery to the public. Freshmen were not allowed to speak at press conferences until January, and even veteran players were only available for 15-minute interviews after games. The team would stay in accommodations over an hour away from their games to avoid both media coverage and opposing teams.

Around 1980, the term “Hoya Paranoia” was born. Reporters, students, and other teams used the phrase to insinuate that Thompson was too worried that engaging with the media would interfere with the Hoyas’ winning streak.

Georgetown certainly won a lot with Thompson as coach. During his tenure, the Hoyas had 596 wins and 239 losses, winning 71% of their games. The Hoyas won the 1984 NCAA championship, made several trips to the finals, and were consistently ranked in the top five.

Behind the taped doors was a coach who would later admit that he was quite paranoid—but for another reason. Thompson, Georgetown’s first Black basketball coach, was hired just eight years after segregation legally ended. He was one of few Black coaches in the NCAA at the time and cultivated almost entirely Black rosters at Georgetown.

While other Catholic universities recruited Black players as early as the 1930s, Georgetown didn’t graduate their first Black basketball player until 1969, three years before Thompson arrived. Just 14 years later, Georgetown had an all Black lineup in 1983, a massive change in a country resisting integration at all costs.

Thompson and his players faced racism from basketball fans and the media. To protect his athletes, Thompson set the rules on media engagement, and he bore the brunt of the criticism and racist attacks against his team, according to Thompson’s players and his memoir.

The media resented Thompson’s reticence, desperate to cover his top-ranked Georgetown teams. In an April 1984 article, the Voice’s editorial board rebuked Thompson’s media policies, arguing that if Thompson did not allow player interviews, he should expect negative coverage.

“If Georgetown wants to play the media-dominated game of big-time college basketball, it must play by the rules of the media, to an extent, or suffer the consequence of barbed pens,” the editorial board wrote.

Thompson hoped to shield his young, mostly Black players from the “barbed pens” of a media landscape that racialized and demonized them, his players told the Voice.

“He was trying to protect kids from a world that he knew disliked him,” Milton Bell, who played under Thompson for two years before transferring, told the Voice. “Once you sit at that podium as a Georgetown basketball player in the ’80s, as an African American man, you best believe that the questions will be coming fast and serious. And so it was his own unique, loving way to prepare us.”

The teenage players, fresh out of high school, weren’t used to speaking to national media. The media was unforgiving, broadcasting when players stumbled over words or said something they deemed wrong.

After Georgetown’s 1984 national championship win, freshman Reggie Williams (CAS ’87) got tongue-tied in an interview, emotional because several players lost their parents that season.

“Commentators tried to say Reggie was stupid and went back to that whole thing about our players not deserving to attend Georgetown,” Thompson wrote in his 2020 memoir, I Came As a Shadow. “Don’t throw that judgment on a shy freshman who’s thrust onto live television and gets nervous.”

Media often used racist language to describe Thompson and his teams. In his memoir, Thompson pointed out that the word most often associated with Georgetown men’s basketball in media coverage was “intimidating.” Where other teams and coaches may be called “tough” or “feisty,” Georgetown’s tenacity on the court was almost always associated with physical violence.

The Boston Globe once described Georgetown basketball as “sick, paranoid and petty, pompous and arrogant.” When Thompson denounced the comments as racist, Sports Illustrated writer Curry Kirkpatrick accused Thompson of “wield[ing] his race like a baseball bat.”

News media speculated about the academic capabilities of Georgetown’s players as well. Center Ralph Dalton (CAS ’86) told the Los Angeles Times in 1989: “People ask me, ‘What is Georgetown like? Are you dumb? Are the people you associated with dumb?’”

While many K-12 schools were legally integrated by Thompson’s time as coach, they remained racially segregated due to racist zoning policies. Thompson often recruited players from underfunded school districts; he said in his memoir that he believed these young men had the intelligence to succeed at Georgetown, they just hadn’t been given academic opportunities in the past. And, they did—in 1989, the overall Georgetown graduation rate was only 87%, but 97% of Thompson’s players graduated from Georgetown across his 27-season tenure.

While Thompson couldn’t control those stereotyping and harassing his players, he would share his own experiences to try to teach them how to deal with the negative attention.

In his freshman fall, Vladimir Bosanac (MSB ’94), one of only two European recruits during Thompson’s tenure at Georgetown, was the subject of a Voice opinion column criticizing Thompson for recruiting a non-American player.

“The thing bothering me most as we enter into a new round of college hoops is the fact that we have a recruit from Yugoslavia,” the column said. “Is it too much to ask that our basketball program ‘buy American?’”

After having read the article, Thompson took him aside, Bosanac said in an interview with the Voice. Thompson told Bosanac about a game during his third season at Georgetown, when someone threw a bedsheet through the gym window which, according to Thompson’s memoir, was painted with the words, “Thompson the [n-word] flop must go.” In telling the story, Thompson hoped to show Bosanac that he had endured prejudice too, but that he would get through it.

“He sort of said something along the lines of like, ‘I want you to know that you’re one of mine and I’m gonna protect you like my family,’” Bosanac recounted to the Voice.

In 1981, elite recruit Patrick Ewing (CAS ’85) arrived on the Hilltop, sending the media into a fervor.

“Once Patrick got there, it put us on a national level,” said Gene Smith (CAS ’84), a member of Thompson’s 1984 NCAA championship team and Ewing’s former teammate. “It was such a clamor for access. That’s when Hoya Paranoia was in its heyday.”

On a roll and starring the most-watched freshman in the nation, all eyes were on Georgetown. Many of those eyes didn’t like what they saw: Georgetown’s entire roster was Black, led by a 6-foot-10 Black coach. Ewing’s renown led him to become one of the biggest targets of the racist attacks.

“I didn’t know about the extensive amount of death threats that Patrick received while he was there,” Smith said. “[Thompson] didn’t mention that to the whole team for fear that, you know, you don’t need that burden.”

In his memoir, Thompson recalled a moment in the 1981-82 season when someone called the Georgetown switchboard and told the operator, “Please tell me Patrick Ewing’s room number because I want to kill him.”

“They can talk about Hoya Paranoia all they want. It ain’t paranoia if they’re really out to get you,” Thompson wrote.

During a 1983 game against Providence, Thompson pulled his team off the court and didn’t return until a sign saying “Patrick Ewing Can’t Read” was removed from the stands. Signs and shirts displaying similar messages were often seen at games. Thompson wrote that spectators would throw bananas onto the court, likening Georgetown’s Black players to apes.

“There’s some cruel people in this world,” Brown said. “I mean they’re talking about 18, 19-year-old boys, for lack of a better word, and you would not know it from some of the things that you were hearing in the crowd.”

Many non-Black Americans and basketball fans turned against the Hoyas during Thompson’s time as coach, according to his memoir. A 1982 Washington Post headline read, “All America’s ‘Villains?’ Hoyas’ Rep a Bad Rap.” When the team would enter other arenas, opposing pep bands would play Darth Vader’s Theme.

“We embraced the us-against-the world mentality,” Smith said. “I don’t think we embraced it to the point where it motivated us, but we certainly embraced the Darth Vader role.”

Yet, as the team became targets for attacks from much of the country, Black Americans rallied around them.

“Every African American kid from the inner city, we all wanted to play for Coach John Thompson,” Bell said. “He was a beacon of hope for us African American kids.”

Brown, who grew up in a predominantly Black area of rural Louisiana, was surrounded by Georgetown fans back home. Most had never visited the university, they were simply fans of John Thompson, his players and what they represented. As Brown traveled the country with the team, he saw Black fans from home in the stands supporting the Hoyas.

“Everybody in my neighborhood and everybody throughout the state of Louisiana—the Black people—everybody was a Georgetown fan,” Brown said.

Across the country, the Georgetown starter jacket became a status symbol in Black communities, according to players. In fact, it became a somewhat common misconception that Georgetown was a Black university, simply because of Thompson, his mostly Black teams, and their large Black fanbase.

“I can’t count how many Black people came up to me in airports and other public places to say, ‘Thank you for what you are doing.’ They weren’t just talking about winning games. They were talking about how we represented ourselves as a group of proud, intelligent Black men who showed up wearing coats and ties, who graduated, who were faced with racism and overcame it,” Thompson recalled in his memoir.

Smith had similar experiences meeting other basketball players after graduating.

“I lived in New York for 15 years. I had St. John’s players, I had Connecticut players telling me how much they loved our program—and this is the competition—and what we represented,” Smith said.

Today, Georgetown’s basketball team isn’t as closely associated with Black America as it was during Thompson’s era. To Smith, Thompson’s time was a special moment that couldn’t be replicated.

“It was always Black America’s team. I hear people speak in reverence about it,” he said. “That has to be something organic, right? You can’t put that into a bottle. You can’t put what was accomplished, how we were received, what the challenges were, how we dealt with the challenges—that’s all on the fly.”

Thompson and his players paved the way for the NCAA basketball of today, in which Black players comprise 50% of men’s teams and 36% of women’s teams. While today’s Black athletes no doubt deal with racism and exploitation, the Hoyas were a novelty in their era.

Was he paranoid? Sure. Thompson wrote in his memoir that he was wary of the press and how they could affect his game.

But behind the locked doors and taped windows of McDonough Arena was a group of young Black men shot into the spotlight and made symbols of a movement. And at the helm, towel over his shoulder, was Thompson, their “paranoid” protector.

“He shielded us,” Brown said. “He was literally our protector, and I’m forever grateful to him for that.”