This March, after striking the perfect ratio of Lau time to lawn time (which is to say, a whole lot more of the latter), I proudly proclaimed this spring to be a “sidequest semester!”

I fill my weekends with random excursions, visits from long-distance friends, and even a spontaneous trip home—which admittedly felt less whimsical after the six-hour flight. My school days are packed with off-campus lunch plans, long runs across D.C., and a whole lot of time outside.

“I’m at the point in my life where I just carry my hammock wherever I go,” I told my mom one day on the phone.

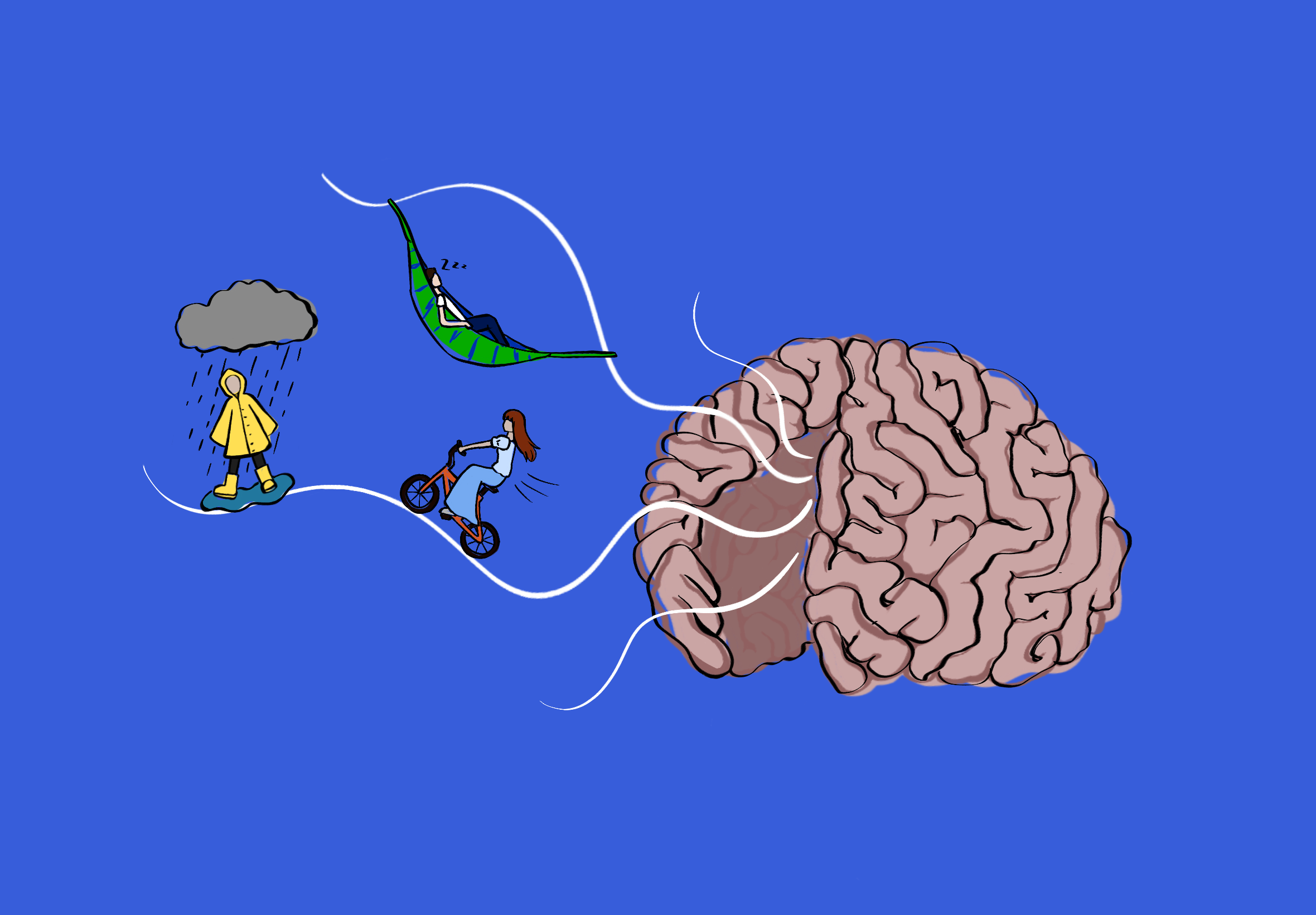

I’m no neuroscientist, but I think if you cut open my brain you would find a bunch of cartoon-style blueprints of my latest plans accompanied by a too-long voice memo explanation.

To a certain extent, I think this love of sidequests is genetic. You cannot convince me that my 6-foot-5 double varsity athlete brother’s decision to spontaneously join the school musical his senior year was not rooted in our unique genetic code—or perhaps was striking evidence of the Troy Bolton effect.

Biological or not, I am a strong and faithful believer in the parts of one’s life making absolutely no sense together. Instead of obsessively centering your precious college time around a post-grad career, find joy by filling your days with schemes, side quests, pranks, and plans. Not to fall into cliché, but you are so much more than your LinkedIn experiences or CommonApp activities—seriously.

With a shocking lack of scholarly research, I must instead turn to the experts in my own life. My pranking sidekick (or perhaps me, his), Alden, is the ultimate schemer. He pumps whimsy into both the endless chaos of our summer as camp counselors and the more sterile aspects of adulthood. He finds happiness in the simple parts of life: a bike ride to work, rainy day adventures, or even the search for a battery recycling location—this last one was somehow the most exciting to Alden. He prioritizes these activities, valuing seemingly ‘childish’ choices like climbing trees and doing cartwheels simply because they bring joy. For Alden, the floor is always lava.

While Alden’s all-encompassing embrace of schemes might seem daunting, micro-dosing unpredictability could be the solution for those addicted to rigid routines. Discover new music, challenge your dining hall habits, or maybe even take a class in a new department.

To an untrained eye, a sidequest can seem embarrassing; not everyone has subscribed to this lifestyle. Understanding—and I mean truly internalizing—the idea that “the worst they can say is no” is a prerequisite. It is easy to get stuck in the hypothetical world of predicting others’ reactions. If you’re caught up in what other people think of you, walk away from campus; strangers are an infinitely less daunting audience.

To redirect toward a life of whimsy, it is necessary to separate who you are from what you do—while the clubs and subjects you spend your time on are important, this form of identity building can be restrictive. On a campus full of resumes and Georgetown intros, it seems our identities are shaped by our majors, clubs, internships, and well-rehearsed interview responses. However, the most interesting parts of your character certainly go beyond this.

Who are you? Your friends and siblings, the teams you root for, foods you love, your favorite places, and any other part of your identity that doesn’t necessarily fit on a resume deserves a more prominent place in that response.

There is a deeper psychological benefit of this redirection away from pre-professional posturing and toward schemes and other silliness. It’s a lifestyle largely and beautifully devoid of caring what other people think of you. This may seem impossible, and I too am still rewiring my brain from the throes of the seventh grade. But, without the pull of external validation, there is plenty of opportunity to spend your time for your own sake, perhaps, on a sidequest or two.

My friend Arthur, ever the philosopher, brought up a flaw within the very term “sidequest.” This narrative framing as a side event to distract someone from their “main purpose” can undermine the value of the quest itself, he argues. After all, if a sidequest—or perhaps scheme, to avoid this semantic issue—results in developing a friendship, understanding yourself more, or simply having fun, how can that detract from any overarching goal?

Perhaps we must challenge the concept of having plans entirely. I am all for finding meaning, life passions, and even an interesting career (believe it or not). But a five-year plan can feel limiting. It fails to recognize the nuance of life and the unexpected beauty of everything going “wrong.” It can also create an unnecessary divide between the version of yourself that exists now and the one you hope to be. By contrast, schemes can teach us to be comfortable with spontaneity and see the beauty in an unplanned life.

Unfortunately for the planners among us, it’s impossible to predict the unpredictable. We must live in the madness.

There are plenty of opportunities to market yourself to others. Prospective employers, grad school admissions, and even opinionated relatives will still demand your well-packaged summaries and single-page life stories. Yet, schemes, on any scale, push back against a culture that forces us to live a life that looks good on paper. Rebel by finding joy in the uncertain, whimsical, and random.