Last June, Alexa Rodriguez filed a discrimination complaint against MedStar Georgetown University Hospital with the D.C. Office of Human Rights. The hospital had allegedly denied her request for breast implant surgery on the grounds that she is a transgender woman.

Rodriguez, Vice President of D.C.’s Latino LGBT History Project, had been referred to MedStar Georgetown for the surgery by her primary care physician at Whitman-Walker Health, a D.C. nonprofit community health center that specializes in LGBT and HIV care. Whitman-Walker was providing Rodriguez with the full array of necessary treatments and services to go along with her gender transition, according to a report from Washington Blade, including hormone therapy and mental health counseling.

“Whitman-Walker routinely refers transgender and other patients to qualified specialists, including Georgetown, for health care needs that we do not offer in-house,” the center’s Director of Communications Shawn Jain said in an interview with the Blade. Rodriguez recalled that she had known of other transgender women who had transition-related breast surgery at MedStar Georgetown in 2014. According to Ruby Corado, Executive Director of Casa Ruby, a bilingual multicultural LGBT community center, one of these surgeries occurred as recently as January 2015.

It was then that Rodriguez visited Dr. Troy Pittman, a respected plastic surgeon at MedStar Georgetown who has specific expertise in reconstructive and cosmetic breast surgery, who conditionally cleared her for the procedure. Initially, Rodriguez’s insurer, UnitedHealthcare, denied her request for coverage of the surgery, but reversed its decision five months later in response to her appeal of the denial.

On May 8, Rodriguez called a hospital employee who schedules Dr. Pittman’s appointment to schedule her surgery, only to find out that the hospital was no longer taking transgender women for treatment or surgery. According to Rodriguez, one of her female transgender friends was denied breast-related surgery from Georgetown that same week.

Representatives of MedStar Georgetown could not be reached for comment for this story, but in a statement released to the Blade, Marianne Worley, Director of Media Relations for MedStar Georgetown, explained the decision by saying that the hospital has a policy of not discriminating against patients based on sexual orientation or gender identity and expression, among other categories. “A high-quality gender transition service is best delivered in the context of an integrated program rather in a one-off manner, and such a program does not exist at MedStar Georgetown,” she said. As it stands, because it chose to deny Rodriguez treatment due to her identity as a transgender woman, MedStar Georgetown could be in violation of the Human Rights Act of 1977. Should the hospital be found guilty, it could appeal the verdict, and the case could find its way to the federal courts.

Megan Howell

Rodriguez’s story is one that didn’t receive much press coverage outside smaller D.C. media organizations, yet the story made waves in the district’s LGBTQ community. And for the transgender members of Georgetown’s student body, the incident served as an unwelcome reminder that the sorry state of transgender health care in the United States follows them to campus.

****

This was not the reality that Miller, a transgender man, faced.

Andrew Sullivan

Every day, transgender and gender nonconforming people face marginalization due to their gender identities, which can prevent them from finding work and getting housing. The effects of this marginalization have a profound impact on their health outcomes.

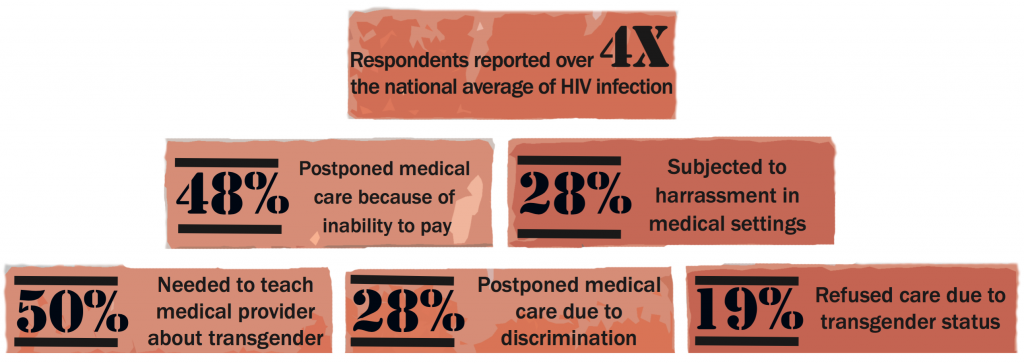

A 2010 study by the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force found that transgender and gender nonconforming people reported what were deemed to be very high levels of postponed medical care when they were sick or injured: 28 percent due to discrimination and 48 percent due to an inability to afford care.

Respondents also faced significant hurdles to accessing care. Fifty percent of the sample reported having to teach their medical providers about their specific health care needs. Nineteen percent of the sample reported being flat-out refused care due to their transgender or gender nonconforming status.

Unfortunately, this population represents some of those in the most dire need of medical care. Respondents in this survey reported an HIV infection rate over four times larger than the national average. More than a quarter of the population report the misuse of drugs or alcohol specifically to cope with discrimination. And worse, 41 percent report the attempt of suicide, compared to 1.6 percent of the general population.

For Miller, who serves as the Vice President of Community for GU Pride, and other transgender students on campus, some of the health care institutions at Georgetown, like the SHC, MedStar Georgetown, Georgetown Emergency Response Medical Service (GERMS), and Counseling and Psychiatric Services (CAPS), seem as unwelcoming as these statistics might indicate. Though he has been to the SHC for issues unrelated to his gender identity, when asked by his friends why he waited for over a week to seek treatment and help for his mono, Miller expressed unease.

“I just didn’t want to deal with [them],” he said.

****

This trepidation toward Georgetown’s health care institutions is common among the members of the small population of out transgender and gender nonconforming students. One member of this community, Lexi Dever (COL ‘16), a transgender woman and a Student Assistant for the LGBTQ Center, initially expressed her apprehension about these services in absolute terms “[I have] never [visited]the Student Health Center, I’ve never called GERMS, and I have no intention of those things changing,” she said. Dever, like Miller, attributes this steadfast hesitance to a belief that these institutions are not suited to meet the specific needs of transgender students. [pullquote]“I’m just not confident that I will be treated properly as a transgender individual … Many doctors don’t know what to do when they have a transgender patient.” – Lexi Dever[/pullquote]

Dr. Matt Schottland, a staff psychologist and LGBTQ specialist at CAPS, agrees. “I think [that]to better address needs of transgender students, health care institutions at Georgetown can better educate their staff about issues specific to this population,” he wrote in an email to the Voice.

[pullquote]According to Schottland, these institutions need to do a better job educating their staff to promote knowledge about the issues transgender students face, including discussion of appropriate language and a “thorough examination of one’s own biases, assumptions, stereotypes and privilege.”[/pullquote]

This information is vital to being able to adequately treat any issues that transgender students may encounter. “This would include, but not [be]limited to, hormone treatment, referrals, [and]when appropriate and asked about, to clinics specializing in sex reassignment surgery, health problems that may arise related to the biological sex of the individual, etc,” he wrote.

But while GERMS appears to be taking steps to adapt to the changing needs of transgender students, the Student Health Center did not point to any concrete plans for the future. “At the Student Health Center, we work sensitively to understand and address the health needs of all our students,” SHC Director Roanna Kessler wrote in an email to the Voice. “I envision the role of the SHC to be a place where students feel comfortable sharing their unique health concerns and establishing their primary care medical home while they attend Georgetown.”

“I just don’t think they’re concerned, to be honest,” said Renleigh Stone (COL ‘17), regarding the SHC. Unlike Miller and Dever, Stone, a non-binary trans person and the Co-Chair of GU Queer People of Color, occasionally visits the SHC for matters unrelated to their gender identity. “I’ve never seen anything about trans resources, like pamphlets or anything. I’ve never heard of anybody there asking about pronouns,” they said.

Yet while Stone is clearly unhappy with this situation and wants to change it, they do not seem surprised by how little those at the SHC seem to understand their identity. “I’m just really good at lowering my expectations,” they said, “I don’t really expect that much out of [the SHC].”

****

Data from a 2010 study by the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force

“I’ve never seen anything about trans resources, like pamphlets or anything. I’ve never heard of anybody there asking about pronouns,”

– Renleigh Stone

“We have a lot of conservative donors, and we don’t want to lose our Catholic affiliation,” they said. “So there are a lot of barriers.”

With that being said, the situation for transgender students has certainly improved in the last few years. “I’ve definitely gotten the vibe from administrators I’ve talked to about trans issues in general, that the people in the University care, and they do want to be supportive,” Dever said. “They just aren’t sure what to do.”

“That’s further complicated with an issue like health care since the trans community is very distrustful of medicine,” she said. With a community still searching for access to necessary health care, and institutions unable or unsure of how to provide it, it would seem that building trust will be a long and challenging process.

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated from a previous version to include that Willem Miller was once a member of GERMS and to clarify that he has visited the Student Health Center.

“I just didn’t want to deal with [them]”

“[I have] never [visited]the Student Health Center, I’ve never called GERMS, and I have no intention of those things changing.”

What a grand indictment of Georgetown’s healthcare for trans students. As always, the Voice went searching for a grand conspiracy of oppression, found none, then dressed it up as if they had.

What are the differing medical needs of trans people? How are they related or not related to biological sex? How does someone’s body and its processes change during or after hormone replacement therapy?

I assume trans men still need to worry about breast cancer screenings, and trans women about prostate exams (at least pre-op, but given cancer’s sneaky tendency to show up where you least expect it, I wouldn’t rule it out post-op, either). Obviously psychological counseling should be made readily available given the increased rates of discrimination and abuse trans people experience. But what else?