Last Thursday, Georgetown University announced the findings of its working group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation. The group’s recommendations include renaming Freedom Hall and Remembrance Hall, offering an apology, engaging with the descendant community, developing a public memorial, and establishing a new Institute for the Study of Slavery and Its Legacies at Georgetown. The University has agreed to pursue all of these recommendations.

Furthermore, the University has announced that they will offer descendants of enslaved people from whom Georgetown benefited the same consideration as members of the Georgetown community in the admissions process.

This Editorial Board believes these moves are a good first step toward reconciliation for Georgetown’s historical connection to slavery. But they ultimately do not do enough to benefit the descendants of enslaved people who worked for the Jesuits.

Georgetown would not exist as it does today without slavery. Its oldest buildings were built with slave labor. Its first students brought slaves with them to campus. Its debts were paid by the selling of slaves. The monetary benefit that slavery conferred on Georgetown is incalculably large. As Fr. David Collins wrote in his New York Times op-ed, “slavery is our history, and we are its heirs.”

Many have made note of the recommendation for preferential admissions. In reality, this policy stands to benefit only a small number of descendants. Many are past college-age, and it would be presumptuous to think that those who are not would all want to or be positioned to attend Georgetown. The University’s plans for reconciliation do little to help these people.

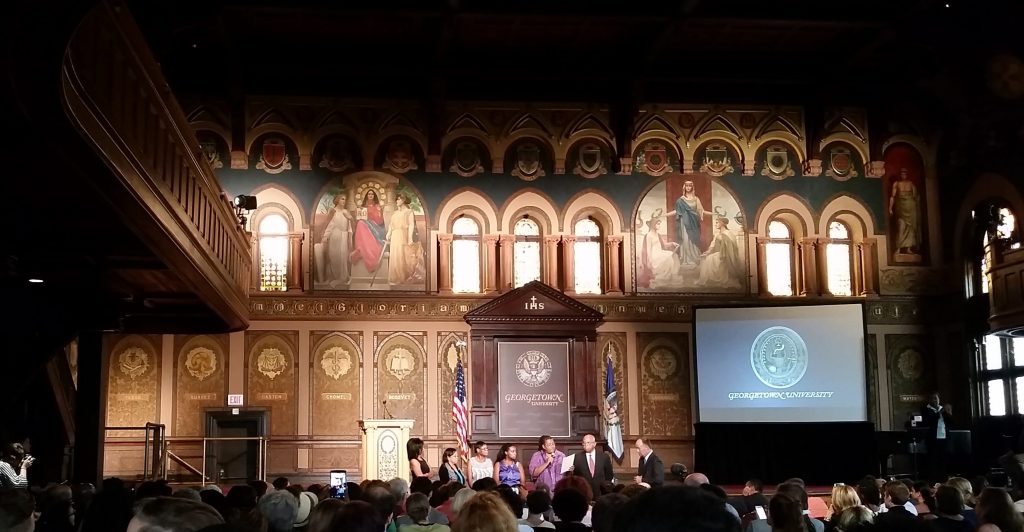

University President John DeGioia commented on the Working Group’s report at an event yesterday. Photo: Kevin Huggard

That being said, the rhetorical aim of this move, which treats the descendants of slaves who built our University like legacy students and full members of the Georgetown community, is not lost on us. It should be highlighted, however, that this move has limited practical impact. As it stands, about 80 to 90 percent of legacy students would have been accepted to Georgetown regardless of their legacy status.

This is why we believe that only giving these students a slight advantage in the admissions process does not provide a financial benefit even close to equivalent of the costs borne on the backs of the enslaved people who worked for Georgetown.

At the very least, offering full scholarships to the students who qualify for these preferential admissions seems necessary to ensure they do not leave Georgetown with the student loans sometimes included as part of financial aid packages and to meet the University’s stated desire of a “meaningful financial commitment” to the descendants. Offering payment to other descendants who do not qualify for admission to Georgetown should also be strongly considered, as it would appear more in line with the working group’s call for a “meaningful financial commitment.”

Granted, we recognize that the financial benefits we received from enslaved people’s labor are far too great for Georgetown to pay back directly. We are also unsure whether descendants of those slaves who worked at Georgetown would want a direct payment.

One descendant, Melisande Colombe, described her vision of reconciliation to The Washington Post. “Money—no. I can’t be compensated financially for that,” she said. “But as Americans, are we not obligated to open up a dialogue to truth and reconciliation? For ourselves—for our children—for future generations. We can’t keep telling the same lies.”

Indeed, the recommendations neglected to include what descendants want, something that has made Georgetown vulnerable to criticism regarding its efforts thus far. But we are encouraged by the University’s expressed desire to actively reach out to descendants and invite them to join in its efforts. It is dangerous to presume that the university knows best for those affected by its harmful actions, and the university should work with descendants to determine what the best course of action should be, especially concerning the possibility for reparations.

One idea, proposed by a group of descendants, is for Georgetown to establish a $1 billion charitable foundation to continue the work of reconciliation. A spokesman for the group, Joseph Stewart, told the Post that “Our vision is not about reparations. It’s not about getting anything that just benefits descendants. It’s about having an opportunity to have a common good.”

Georgetown’s commitment to work with descendants must be more than just talk. To this end, the University should establish a strict timeline for future plans on reconciliation and faithfully abide by them.

Several descendants have already shown a desire to be an active part of the process of reconciliation. Karran Harper Royal told the Post, “You can’t have a healing and a reconciliation without mutual respect and collaboration. We are ready to do that,” she said.

Slavery was a national sin, and Georgetown does not have the capacity to address it in its entirety. As the report of the working group makes clear, Georgetown’s “origins and growth, successes and failures, can be linked to America’s slave-holding economy and culture.” The University’s reconciliation efforts should be linked to a wider cultural movement within American higher education. In the past, other schools such as Harvard, Brown, and the University of North Carolina have published histories or erected memorials about their ties to slavery, but none has gone so far to offer an official apology as Georgetown has agreed to do. As one of the first universities, and indeed one of the first institutions, in the United States to do so Georgetown is in a unique position to lead a response to this history among its peers.

We are encouraged by Georgetown’s membership in Universities Studying Slavery, a working group consisting of scholars representing twenty universities in and around Northern Virginia, and by potential collaboration between universities on this shared history. We envision a collective scholarship program that allows any descendants of the enslaved people connected to any of the universities within the consortium to receive full scholarships to any of the schools within the consortium that offers them admission.

We acknowledge that a program like this still does not absolve Georgetown and any partner institution of their dark history with slaves. Yet we believe that these larger programs get us much closer than simply offering preferential admissions.

Georgetown has taken an important step, but the work is far from finished. While the University has devoted significant resources toward this effort, more is needed. In addition to the programs outlined so far, progress will require a readiness to extend the financial benefits of reconciliation to the descendants of Georgetown’s slaves beyond the small percentage of that group that may study here. With an evil as enormous and long-running as slavery, the project of reconciliation must also be both massive and continuous if anything like justice is ever to be approached.