“It may be important to great thinkers to examine the world, to explain and despise it. But I think it is only important to love the world, not to despise it, not for us to hate each other, but to be able to regard the world and ourselves and all beings with love, admiration and respect.”―Herman Hesse, Siddhartha

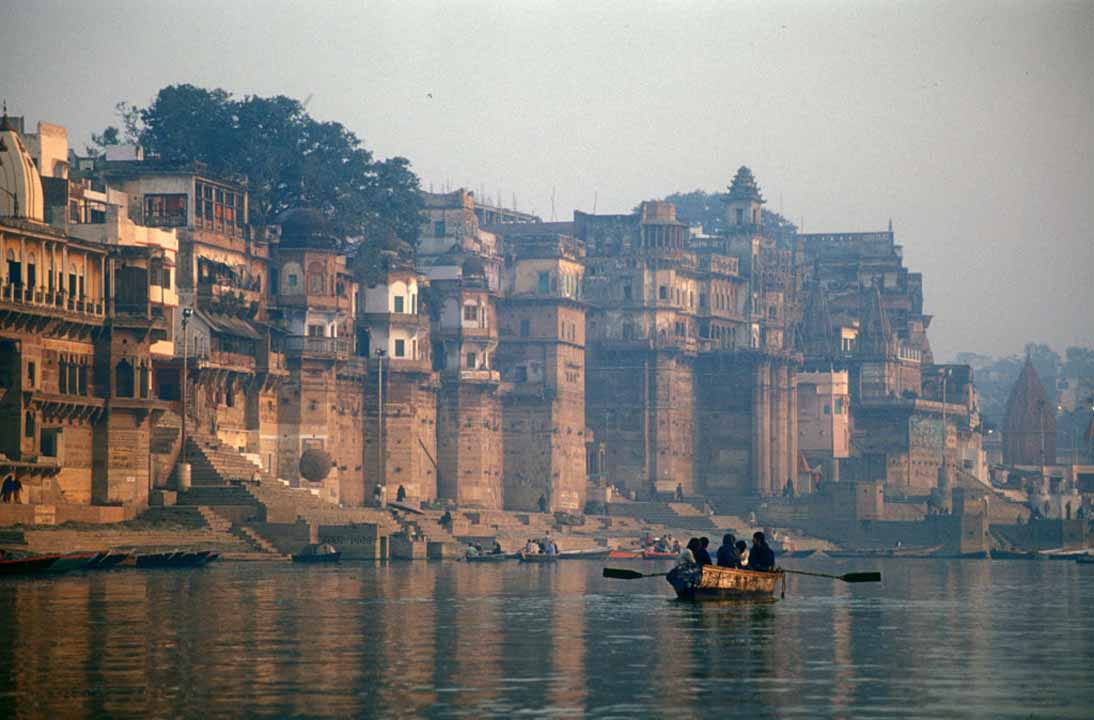

Herman Hesse’s eighth book, Siddhartha, describes a painstakingly simple spiritual journey of self-discovery. The eponymous hero is the young, handsome son of a Brahmin who is cursed with an unquenchable internal thirst, a fiery agitation, the desire to find enlightenment. His spiritual disquiet takes him from his father’s house to a group of ascetics who live in nature and lead a life of renunciation, denying themselves any kind of material satisfaction, believing the physical world to be the source of all pain. He then meets an enlightened individual and comes to the realization that the nirvana he seeks lies within him and involves getting in touch with himself. Deciding to leave the asceticism he previously espoused, he travels into the city, meeting a beautiful courtesan who reveals to him the universe of sexual desire and the mysteries of physical love. She puts him on the path of pleasure, leading him to a life of hedonistic excess in which he becomes a wealthy merchant. Waking up one morning overwhelmed by what his life has become, he leaves the city and finds himself at the river, spending the remainder of his life listening and learning its secrets, aided by a mysterious ferryman.

Hesse’s novel recounts the beautiful process of self-discovery. Its magic lies in its succinctness, its simplicity, and its relatability despite being a spiritual journey from the Eastern hemisphere. The uncomplicated narration contains incredible pieces of soft wisdom, and the significance of such a journey is translated in fewer than 200 pages. Upon learning that Siddhartha’s journey is a reflection of the German author’s very own struggle to find contentment and peace, the reader is even more taken by just how relatable a seemingly fanciful and foreign story is. The varying reactions to Hesse’s novels stem from the common western reaction to and perspective on ideas about spirituality and enlightenment. His readers divide themselves into those cynics who are critical of this whimsical obsession and those who are actively seeking this contentment.

Siddhartha highlights the differences between the proponents of the western traditions of cynicism, fatalism, and existentialism, and the westerners who have looked to the east for spiritual awakening, those who want more out of life, seek more out of each daily activity and force themselves to see more in small things. This is not a discussion of whether the elusive and ambiguous ‘more’ is really there and much more complex than a war between pessimists and optimists. The reaction to Hesse’s novel brings forth the very important issue of life being a matter of picking one’s perspective. I only arrived at being someone completely enamored with the idea, feeling, and practice of contentment after taking a very deep dive into cynicism and existentialism. The allure of this dark pit is undeniably strong. Cynicism gives humans incredible power by creating the idea that, by assuming the worst of people and the world, one is always ahead. It removes the potential of being disappointed, fashioning the illusion that one is somehow above everything. Yet one mustn’t ignore the fact that this attitude simultaneously places individuals both ‘above’ the mess of human nature and deeply entrenched in its depravity. It is impossible to rid oneself of the feeling that one’s boots are trapped firmly in the mud of a weedy, fetid swamp.

These cynics, noses scrunched at the stench of impermanence, hedonism, and self-interest, somehow manage to look down at the seekers of enlightenment, reveling in the laughable characteristics of these hippies, flower children, free spirits. But what exactly is so ridiculous about their attitudes? There is no fault, no sin in adopting an attitude similar to Siddhartha’s. There is nothing to be lost and everything to be gained by placing oneself on a path of spiritual seeking. There is no reason to deny oneself more happiness. Humans must recognize that this choice of perspective is the fundamental decision that will determine how they live their lives and how much they let themselves get out of their lives.

Embracing the possibilities, the potential, that comes with seeking contentment requires accepting that this ‘bad’ does indeed exist and is in fact quite ubiquitous. It also consists in, however, the decision not to contribute to it, to accept it as fact and to rise above it, to be more than what the worst of human life can represent. It is the decision to make oneself vulnerable to disappointment, the only way to allow oneself to feel both the good and the bad. Siddhartha’s spiritual journey that takes him to enlightenment is a model that easterners and westerners alike can emulate. It is still possible to look into oneself and learn about peace and happiness without living with ascetics and courtesans or listening to a river say ‘Om’. The lesson to be in touch, with the self, other individuals, and our world is inapplicable without the making of a conscious decision. This decision requires a formidable amount of courage, yet brings with it the promise of every cliché, deliciously tempting with whispers of sweet everythings about the peace that lies just around the corner.