Senator Charles E. Grassley (R-IA) was on the warpath. In 2008, Grassley, the ranking member on the Senate Finance Committee, had perceived a disturbing trend in higher education: colleges and universities were hoarding their fat endowments while failing to provide enough financial aid to make college affordable. So in late January, Grassley asked over 100 U.S. colleges and universities to provide the Committee with information about endowment growth, tuition size, and financial aid policies.

A month later, on February 25, Georgetown University President John DeGioia sent a 21-page response that conveyed a simple message: you’ve got nothing to worry about from us.

Though ranked in the top 25 universities nationally, DeGioia noted, Georgetown’s endowment, then valued at just under $1.06 billion, ranked 73rd. All but two schools ranked above Georgetown had endowments more than double the University’s. The endowments of fifteen schools were at least five times larger.

“I make this point to emphasize to the Committee our pursuit of academic excellence while maintaining our commitment to access and affordability,” DeGioia wrote. “In comparison to our peers, I think it is very fair to say that we are doing more with less.”

If Georgetown’s financial history—at least in the past forty years—has to be characterized in three words, it would be “more with less.”

Since 1969, when newly-inaugurated President Robert J. Henle, S.J., embarked on a mission to vault Georgetown from mid-Atlantic obscurity into the ranks of the nation’s elite universities, Georgetown has stretched every dollar.

The initiatives he started—increasing financial aid and faculty salaries, boosting Georgetown’s academic programs, investing more in on-campus facilities—helped Georgetown develop a reputation for academic excellence. The number of applications to Georgetown exploded soon after. The University’s seven-point victory over the University of Houston in the 1984 NCAA Men’s Basketball Championship didn’t hurt either, and a larger, more selective student body soon followed.

Old habits die hard though, and despite cultivating the academic and athletic character of a top university through the 1970s and 1980s, Georgetown retained the financial management practices of a small, regional Jesuit university.

“Prosperity tends to make you a little bit sloppy,” Provost James O’Donnell said, referring to the influx of new students and, by extension, tuition dollars. “We didn’t feel driven to professionalize our financial management because we had money.”

Large-scale fundraising, by then second-nature at other top universities, was non-existent at Georgetown until the mid-1990s. As other schools developed sleek investment operations, Georgetown’s endowment was still managed by outside volunteers acting on quarterly instructions from an investment committee. And, following the failure of President Bill Clinton’s (SFS, ‘68) health care reform plan in 1994, Georgetown Hospital became a sea of red ink, accounting for roughly half of the school’s financial activity by 1999.

Fortunately, a lot can change in ten years.

DeGioia, then Senior Vice President, stanched the Hospital’s most serious financial bleeding by engineering its sale to MedStar, the hospital management non-profit, in 2000.

Three years later, DeGioia hired Chris Augostini, previously Chief Financial Officer of the Georgetown Law Center, to serve as the CFO of the entire University. In July 2004, Georgetown hired Lawrence Kochard as its first Chief Investment Officer, a landmark in Georgetown’s transition to a modern investing operation, making decisions daily rather than quarterly. And in July 2005, following the completion of its first billion-dollar fundraising campaign, the University recruited James Langley, fresh from a successful $1 billion campaign at the University of California, San Diego, to be its Vice President for Advancement in charge of alumni relations.

Although the effects of Georgetown’s past linger—from the University’s still-stunted endowment to its “modest lifestyle,” as Langley put it, to its underdeveloped fundraising base—the developments in the last ten years represent an unprecedented professionalization of Georgetown’s financial management. For the first time in its 220-year history, administrators say, Georgetown has achieved a level of financial expertise and sophistication that rivals even its most advanced peers.

After being hired as CFO, Augostini focused on creating and implementing a conservative five-year financial plan for the University, as well as managing its debt. This long-term perspective as well as the University’s conservative management strategy positioned Georgetown to weather the financial crisis better than many of its peers.

Mary Peloquin-Dodd, a managing director specializing in higher education and non-profits at Standard & Poor’s, cited Georgetown’s more sophisticated management and the implementation of its five-year plan as factors in Georgetown’s S&P credit rating upgrade in September 2008 from BBB+ to A-.

Similarly, Langley began to improve Georgetown’s fundraising and alumni outreach apparatus. After arriving, he launched a discovery initiative to build alumni relationships and to identify potential donors to Georgetown, beyond the limited pool of donors O’Donnell said it had previously relied on.

“You’ve got to go out almost like a political campaign and build a constituency, building a following,” Langley said. “Take a message out. Organize.”

That message is Georgetown’s rapid ascent through the last half-century to the top tier of U.S. higher education on the strength of relatively sparse resources. “What that says to our potential investor is, your dollar goes far here,” Langley said. “This is a place that does convert investment to significant academic achievement. So that’s our story. This is why you should give.”

Langley also focused on building and supporting professional networks in the eight major cities where 75 percent of Georgetown alumni live, including a Wall Street Alliance in New York, a High Tech Alliance in San Francisco, and a Latin American Alliance in Miami.

“We had to race to create many of those structures because they simply weren’t in place,” Langley said.

The big shots: Lawrence Kochard, Chris Augostini and James Langley are modernizing Georgetown’s finances.

The most significant change at Georgetown, though, came from Kochard, who, despite repeated requests, was not available to be interviewed for this story. With the establishment of the University’s investment office, Georgetown finally enacted practices adopted decades ago by other elite schools: day-to-day management of investments, the use of a full-time staff, and an investment philosophy and asset allocation guidelines suited to the needs of the institution.

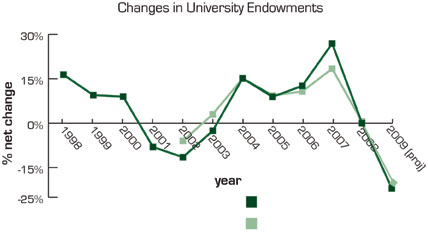

The difference was palpable. Prior to Kochard’s arrival, Georgetown’s endowment had underperformed the average return of U.S. universities and colleges by 5 percent in 2002 and 2003, according to data from the National Association of College and University Business Officers’ annual endowment study. In 2006, Georgetown outperformed the benchmark by 1.9 percent with a 12.6 percent return.

The next year, the endowment broke the billion dollar mark for the first time on the strength of a 26.9 percent return, more than 10 percent above the average institution. Foundation and Endowment Money Management, an investment magazine, named Georgetown’s endowment “Large Endowment of the Year.”

But the true test of Georgetown’s new financial management came when the bottom fell out of U.S. financial markets. Late in 2008, the University found itself facing the most severe economic crisis since the Great Depression. But instead of undoing the progress made in recent years, administrators said, the University reacted to the crisis in a way that affirmed the strength of its financial management.

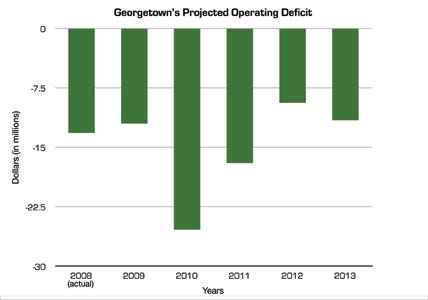

The hit that Georgetown has taken is not insignificant. According to projections, the endowment shrunk to $900 million, or by about 22 percent, in the fiscal year 2009—which is roughly equal to the average decline of U.S. universities and colleges. But the University avoided major budgetary cuts to Georgetown’s core academic programs, Augostini said, and has not laid off any staff, unlike six of the eight Ivy League schools.

“When you look back on our response to the crisis, we preserved the culture of the institution and the things that are most important to us during a time when many of our peers had to abandon those items,” Augostini said. “I think we as an institution should be very pleased about how we will have come out of this period.”

Of course, Georgetown had two key structural advantages: first, a low dependence on its endowment for funding its budget, 6 percent of a five-year average, compared to an institution like Harvard, which depends on its endowment for almost half of its budget; and second, no reliance on state legislatures, which have slashed university budgets, for funding.

The budget reductions froze faculty and staff salaries through 2009 and salaries for senior administrators through June 2010. Conversely, in response to greater need from the student body, the University allocated more, not less, financial aid during the financial crisis—increasing its funding by 18 percent. Tuition was increased by 2.9 percent, less than half of the previous year’s change.

Then there’s the matter of the science center, which is currently nothing more than a stretch of naked dirt in front of the new Rafik B. Hariri Building. The University had been planning to borrow $50 million to finance its construction, but constricted credit markets made it difficult to find a source of affordable financing. The recession ultimately forced the postponement of construction, which was scheduled to begin last year.

But by delaying the project, Augostini said, Georgetown has deferred both the estimated $105 million cost of the building and the annual operating cost of $10 to $12 million. Universities that have financed capital projects with debt in spite of the recession have ended up paying up to four times normal interest rates, according to Kenneth Redd, the Director of Research and Policy Analysis for NACUBO.

Moreover, since Georgetown had already built expenses from the science center into its annual budget, the delayed construction freed up money to ease the pressure for cuts in other areas.

“That gave us a little cushion that by postponing the science center we could count on,” O’Donnell said. “We were lucky we had been saving a little.”

Once funding is secured, administrators are emphatic that the science center will be completed. “We’re going to do the science center,” O’Donnell said. “We’re going to do it soon.”

Two other components of Georgetown’s response to the crisis—the restructuring of debt and increased liquidity in the endowment—will likely have long-term implications for Georgetown’s finances. The University now seems willing to tolerate lower investment returns and higher interest rates on its debt in order to maintain a less volatile financial position. In layman’s terms, Georgetown’s conservative strategy carries lower reward with lower risk—a prudent position in the current economic climate.

Georgetown’s debt has also become less risky in recent years. In 2000, Georgetown began purchasing a type of debt called auction-rate securities (ARS), which are variable-rate bonds that have their interest rates regularly reset through auctions. By taking advantage of the robust ARS market in the first part of the decade, Georgetown paid on average 2 to 2.25 percent on a significant portion of its total debt, according to Augostini. At its highest point, Georgetown had $550 million out of a total $800 million debt in ARS.

In early 2008, though, the auctions began to fail and the ARS market collapsed. Georgetown avoided serious fallout, only paying marginally higher-than-budgeted interest rates, and began to aggressively move out of ARS into more stable, fixed-rate bonds. It closed its final conversion out of ARS earlier this term and now holds 65 to 70 percent of its debt in fixed-rate bonds, with an average interest rate of 4 to 5 percent.

“What we have now is a very predictable, very stable debt service structure that will benefit the University going forward,” Augostini said.

This restructuring came at the same time as a move to increase liquidity and decrease risk in the endowment, in reaction to the constrictions in the credit markets—an action undertaken by many colleges and universities, according to Redd, the NACUBO analyst. This meant moving out of higher risk, illiquid investments like hedge funds, private equity funds, and commodity contracts in order to increase the amount of cash in the endowment. By the end of April this year, Georgetown had access to over $300 million from its endowment within a week, according to a Standard & Poor’s report.

How these recent developments will impact Georgetown’s investment strategy in the future is still being discussed by Augostini, Kochard, and the University’s Investment Committee. Augostini said that instead of basing its strategy on asset categories as it has in the past, Georgetown will likely instead base allocations on a target level of risk and liquidity in order to maintain a stable yet modest return on Georgetown’s investments.

“Somewhere between 5 and 8 percent [return] would be, once we go into this recovery … a reasonable benchmark depending on the asset class,” Augostini said.

Investment returns in that range mean that if Georgetown is going to close the gap between its U.S News and World Report ranking, 23rd in the 2010 edition, and its endowment ranking, 71st in the 2008 NACUBO study, the difference will need to come from fundraising. Even in the current economic climate, there’s reason for optimism on this front; this past fiscal year was a record fundraising year for Georgetown by a margin of 68 percent, bringing in about $180 million.

A significant portion of this came from two estate gifts, including the largest in Georgetown’s history, a $75 million from the estate of the late Robert McDevitt (CAS ’40), but Langley pointed out that Georgetown also had the greatest number of donors ever last year, offsetting a smaller average gift.

Georgetown’s fundraising may benefit from the expansion of its undergraduate student body in the 1970s and 1980s, O’Donnell said, as those classes reach an age when they have the means to make greater donations to Georgetown, in addition to early graduates of Georgetown’s MBA program, which was founded in 1981.

“We’re beginning to get the first wave of folks from the first generation of the new Georgetown,” O’Donnell said.

Georgetown’s ambitious upcoming capital campaign, which will aim to raise between $1.5 and $2 billion and will be officially announced in September, has already raised $520 million over the last three years while in the quiet phase, during which the University contacted likely donors to build momentum before the campaign’s official unveiling.

Continually growing the University’s prospective donor base and cultivating long-term relationships with alumni is the key to successful fundraising, Langley said, and ultimately will determine a large part of Georgetown’s financial well-being in the future. Though $1.5 million was cut out of the Office of Advancement’s $30 million budget in response to the crisis, Langley is confident that Georgetown understands the importance of alumni relations.

“The minute you stop investing in long-term relationships, you start mortgaging the future,” Langley said. “You start selling yourself short. Never give up on the long-run. That’s my message back to Georgetown.”