We have to be out of our house by August 1. The word “foreclosure” sounds so foreign—it brings to mind images of credit rating agencies and the “millions of Americans” facing similar fates. I hear the word in the voice of House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) or President Barack Obama, in lofty sentences about job creation and the recession. I hear of these millions, and I don’t number myself among them; their stories seem so distant.

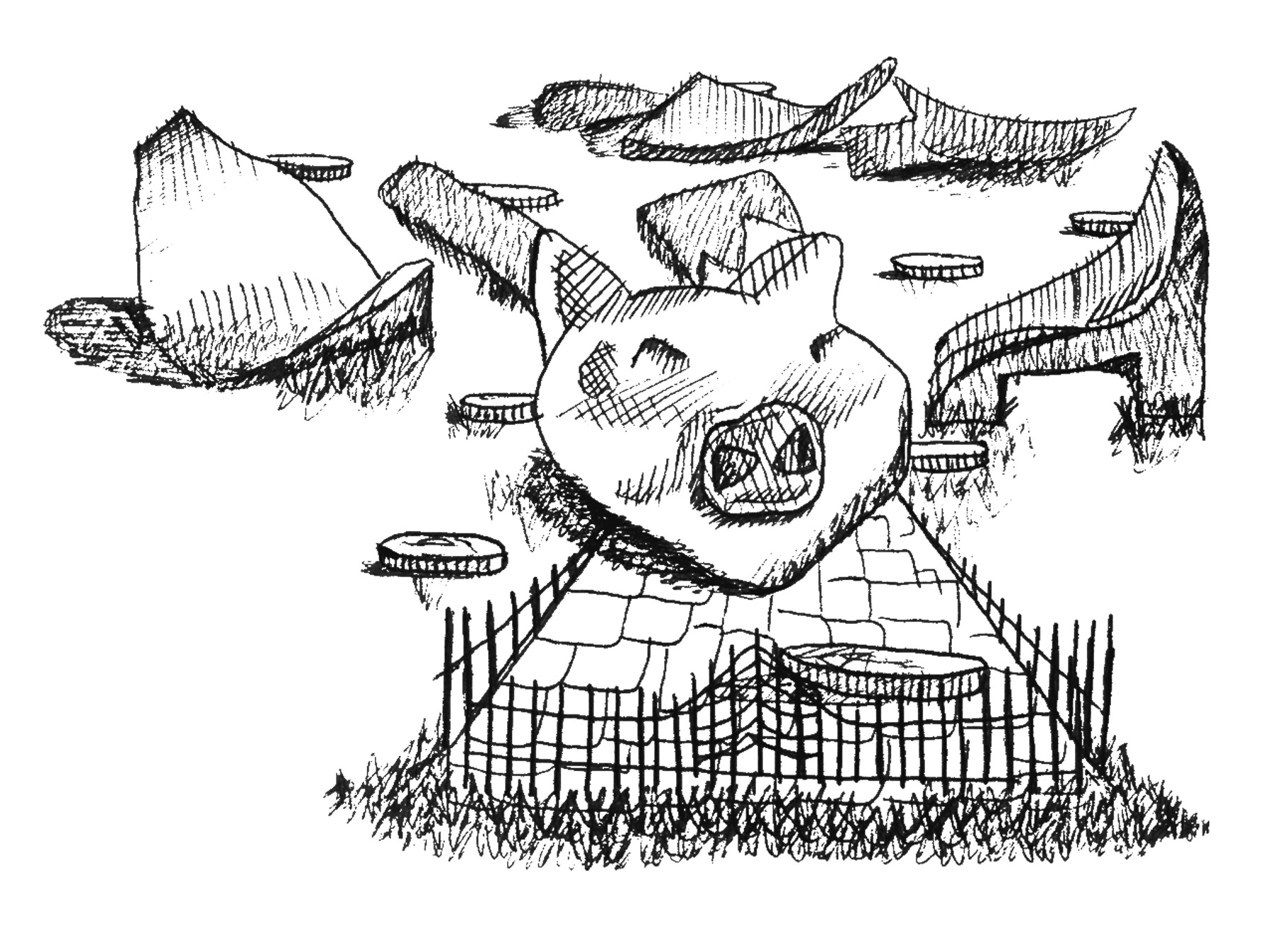

This unfamiliar word is thrown around with terms like “personal responsibility” and the implied stigma. It’s made to sound as though we were financially irresponsible, and we’ve brought this upon ourselves. The word rings of mortgages, however our loss is not a document or a title, it is a home. Foreclosure is procedural, yet nothing about this feels that way. It is messy, inevitable, and unfair all at once.

My parents bought this cheap little beach shack when I was fresh out of preschool, and I struggle to wrap my head around how preposterous it is that an institution can take it from us. This is the house in which we built our secret paradise. I remember months of hammers, the lingering scent of sawdust, and using my father’s power saw for the first time. We pored over paint strips and were besieged with endless splinters from the temporary floors as we renovated. My mother chose every tile and my father framed it himself. I remember my sister’s hair, caked and pasty white, when she dumped her head into a bucket of wet cement as we laid the foundation, and the afternoon my mother and I came home to find our living room open to the public, a three-walled diorama. Now strangers will paint over my rainbow walls and open it up to careless tourists who will smile and remark about how “quaint” it is.

It has been a long process, stalled with negotiations, and after nearly 18 months of waiting, in many ways, it feels as though the Band-Aid is being ripped off. They have given us a concrete date, the inevitable is no longer an abstract obstacle we will one day face, but our reality. However, there is the constant feeling that we really aren’t ready.

I’m not ready to say goodbye, and while I have not spent more than three weeks at home since coming to Georgetown, I feel a melodramatic sense of homelessness. I’m so frustrated—I want to be angry, to blame someone, some intangible aspect of society for doing this to my parents. I want to curse the mythical American dream, because despite decades of hard work, my parents were able to bring themselves out of their own families’ poverty, but never quite achieve comfort or security.

Over these 18 months, I’ve learned immensely. I’ve learned about privilege and perspective, the real meaning of home, and that people are my priority.

At Georgetown, I find I am both incredibly privileged, and yet more disadvantaged by my family’s income than in most communities. Here, unpaid internships are the norm, and expensive brunches and Spring Break rendezvous are expected. I often struggle to explain to my peers why I can’t go to every concert, or why I crawl into work even when I’m sick. And yet, as a Georgetown student, my opportunities are endless. I do have to make sacrifices, but I am not held back, as my outstanding support networks enable my choices. I have learned that in this environment, my will is enough.

As my material possessions get stripped away, I’ve learned to define my priorities. Growing up, I never understood why my mother, feminist-extraordinaire, chose a career of convenience once she settled down. I now realize that there are so many things more important to me than money. I don’t believe in economic primacy. I don’t believe that money will make me happier. Money is merely a facilitator. It can make one’s choices significantly easier or more difficult, it provides and eliminates various opportunities, but it should never be the end goal. I won’t sell out passion for security, or people for comfort.

In many ways, growing up is about internalizing all the clichés you’ve ever heard, and I’ve been learning that home truly is where the heart is. This process began with my journey to Georgetown. I knew then that I was saying goodbye to my home. When I go back, everything will have changed. Dad will still walk in every evening wanting to know if the dogs have been fed or walked, and our doormat will inevitably be saturated with sand, but I will return with new eyes. Everything in my world will change, and I will return to find the residents of Cayucos, my community outside of San Louis Obispo, Calif., haven’t skipped a beat. And yet each time I return home, I find I truly need it. I find myself reflective and contemplative, examining my path and the choices I’ve made.

In many ways, the foreclosure feels like a betrayal. I thought I needed that home base, that town where I cannot help but to be the rawest, truest form of myself. However, since the first notice of foreclosure, I’ve learned that I’ll always find home submerged in the ocean, or driving up the coast listening to James Taylor. And I’ve learned that my home was never comprised of walls and a lot; but rather in the love that seeped through those walls, and the adventures I had on that lot. The comfort of home was never derived from stability, but rather in that it was a family, and a safe space to grow into who I am today.

A sweet story, yet so lacking in relevant details. I write about housing markets around the country and have had 30+ articles published on businessinsider.com. I try to get behind the numbers to give readers a sense of what is really going on out there.

Sadly, I don’t learn from the author why the property is being foreclosed. Was it due to a job loss, a serious illness, or — less likely I suspect — a walkaway? Though the story is a poignant one, why write it? People leave the homes they grew up in all the time. But this is about foreclosure. That means not paying a debt that you are obligated to pay. No spinning that.

I would love to learn what brought the situation to foreclosure. If the family has owned it for a long time, why wasn’t the mortgage paid off? There are many families who actually have a free-and-clear home. Was anything done to try and save the property from foreclosure? Lenders do try to negotiate modifications with cooperating borrowers.

Unfortunately, these questions are left unanswered.