After years of pay and benefit discrepancies between Aramark employees at Georgetown and other D.C. universities, in addition to alleged mistreatment by management, workers gathered on the lower level of Leo J. O’Donovan Hall during their 4 p.m. afternoon break on Jan. 19 of this year to deliver a petition to their employers for fair and equal treatment.

After years of pay and benefit discrepancies between Aramark employees at Georgetown and other D.C. universities, in addition to alleged mistreatment by management, workers gathered on the lower level of Leo J. O’Donovan Hall during their 4 p.m. afternoon break on Jan. 19 of this year to deliver a petition to their employers for fair and equal treatment.

“It really doesn’t matter what the manager says,” Sam Geaney-Moore (SFS ’12), UNITE HERE Local 23 Union Representative for Aramark employees at Georgetown University, said to the assembly of approximately 20 workers. “What matters is that they take up the petition and hear a voice.”

The petition asserts that the workers are not second-class citizens. Demanding the same treatment as the food service employees at Aramark’s other D.C. based branches, including those at American University, Catholic University, and George Washington University, the workers asked for schedules of 40 paid hours, affordable health insurance, meaningful wage increases, protection for immigrant workers, and dignity and respect in the workplace. Over 70 percent of the unionized workers at Georgetown signed the petition.

Marching alongside approximately 30 students, the workers presented the document to then-Regional District Manager Ram Nabar outside the corporate offices located below Leo’s sub-level.

Petition in hand, Nabar assured those assembled that Aramark was in a good-faith bargaining agreement process with the union and working towards “the best solution [they could] work out.” Nabar then asked if there was anything else the employees would like to say.

“40 hours, 40 paid hours,” they chanted in unison, before filing back up the stairs.

The small rally embodied the workers’ frustration, which has grown alongside what employees consider to be Aramark’s reluctance to incorporate these demands into their second union contract. The original contract expired on Dec. 31, 2014. UNITE HERE Local 23 union representatives, voicing the demands of the workers, have been negotiating the terms of this contract with Aramark since October. UNITE HERE has represented Georgetown’s contracted employees at Leo’s, Starbucks, Cosi, and Dr. Mug since 2011.

In spite of being the nation’s oldest Catholic, Jesuit institution of higher learning, Georgetown University still lags behind its counterparts in D.C. in terms of workers’ benefits. Georgetown is the only university in Washington where Aramark’s contract does not require the company to create as many 40 paid hour schedules for its employees as possible guarantee a maximum amount of 40 paid hou schedules for its employees, according to Lauren Burke, the lead organizer for UNITE HERE Local 23.

According to Director of Media Relations Rachel Pugh, the Just Employment Policy demonstrates Georgetown’s commitment to its Catholic and Jesuit values. The JEP is an addendum to university-auxiliary company contracts that aims to ensure a living wage, the minimum wage needed to cover the cost of living in the D.C. area, and was created in 2005 as a result of workers’ rights advocacy by the Georgetown Solidarity Committee.

The wage rate mandated by the JEP, according to GSC member Erin Riordan (COL ’15), is calculated assuming a 40 paid-hour work week. However, after subtracting their 30-minute lunch breaks, total work time for full-time Aramark employees adds up to only 37.5 hours per week, failing to reach the standard for a living wage. Director of Media Relations Rachel Pugh did not respond to multiple emails regarding the number of hours used in the living wage calculations.

While the JEP dictates a minimum compensation requirement, Pugh said it does not elaborate on or define, “full-time.” According to GSC member Caleb Weaver (COL ’16), this in turn prevents the university from legally mandating the number of hours full-time employees need to work. In an email to the Voice, Aramark Communications Director Karen Cutler wrote that the company “fully complies” with Georgetown’s Just Employment Policy.

Securing a living wage is particularly important to the workers because Aramark employees are paid less for their work at Georgetown than they are at other Aramark institutions according to Burke. While a cashier at Georgetown earns $12.10 per hour as of February 2015, a full-time cashier at AU, who is guaranteed 40 paid hours, makes $16.21.

Affordable health care constitutes another key demand for the new contract, since it ensures that employees who do not qualify for Medicare or Medicaid receive coverage for themselves and their families without crippling their ability to pay their other bills.

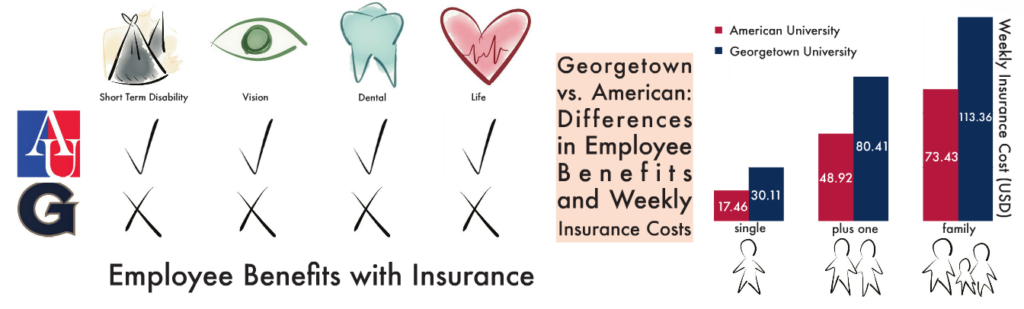

Two and a half miles up the road from Georgetown, Aramark employees at AU not only receive medical, vision, and dental coverage, but their policies cover 100 percent of their medical bills. At Georgetown, workers receive 80 percent coverage during medical visits, have no coverage for dental or vision costs, and pay a higher weekly rate. Additionally, Georgetown employees are not guaranteed the life insurance or short-term disability insurance that contracted employees at AU receive.

While full-time Aramark employees at Georgetown are eligible for health insurance, the number of people each employee chooses to cover determines the cost of his or her plan, which is deducted weekly from their paychecks.

An Aramark employee at AU pays $17.46 per week for single-employee insurance, $48.92 for the employee and another person, or $73.43 for a family plan. On the other hand, his or her counterpart at Georgetown pays nearly double for less coverage, with plans that cost $30.11, $80.41, and $113.36, respectively.

Donté Crestwell, who has been working at Leo’s for 17 years and is a member of the contract negotiation committee, laments the $80.41 dent in his weekly paycheck necessary to insure himself and his son on top of a bill after every doctor’s visit and zero dental coverage.

Alongside many of his fellow workers, Crestwell demands better coverage and that Georgetown employees’ current Blue Cross Blue Shield insurance plan be replaced with Kaiser, the plan available to eligible Aramark employees at AU.

Healthcare conditions have nonetheless improved since the union’s first contract with Aramark. Year-round coverage, according to Burke, constituted one of the previous contract’s key victories. Prior to 2011, workers’ insurance did not provide coverage during months when employees did not work, meaning that during the summer months, when a large portion of students and administrators vacates campus, many employees had no coverage.

Attempting to articulate reasons for such discrepancies, Crestwell said that Aramark employees at Georgetown were the last to unionize in the city.

“Everybody else has a big head start, more experience … But there isn’t a reason why we shouldn’t be treated equally,” Crestwell said.

As Cutler explained, Aramark engages in collective bargain agreements with unions on a case by case basis, so there is no policy in place to extend the wages, benefits, and hours received by employees of one university to those of another in the same geographic area. According to Pugh, Georgetown University is not a party to negotiations between the union and Aramark.

“There’s definitely a distancing that happens which, legally, shields Georgetown from liability of abuses that go on in the workplace because the arbitration of those abuses is now the result of negotiations between the union and the company instead of between Georgetown and the company or Georgetown and the union,” Weaver said.

Deep dissatisfaction with the treatment they receive on behalf of Aramark managers defines many of the workers’ experiences at Georgetown. While some of the alleged mistreatment—including derogatory name-calling and unsubstantiated job terminations—became more heavily regulated after the union instituted a grievance-filing process upon arrival in March 2011, workers continue to report instances of racial discrimination, managerial disregard, and general disrespect.

“You have some management talk to you in any kind of way, holler at you, talk to you like you are a child,” shop stewart and 17-year Leo’s employee Rhonda Smith said. Smith reported that when she attempts to talk back to managers, they turn their backs and walk away.

Starbucks employee China Nguyen encountered similar frustrations when she approached Aramark management with issues of improperly clocked hours and general complaints.

“It goes in one ear and out the other,” Nguyen said. Meanwhile, she and her colleagues down the hall in Hoya Court are not privy to the institutional support of the external grievance-filing process since they were not included in the unionization process in 2012.

In 2010, Antonio Piner was fired on account of what he called “bogus write-ups.” Piner was working in catering and received three write-ups in the same week for incidents of improper set-ups and tardiness that led to his prompt termination. When the Leo’s workers achieved unionization in 2011, the union reinstated Piner after statements from catering clients certified his fine job performance.

According to Riordan, the system for filing grievances that earned Piner his job back is a tremendous benefit of unionization. While the university ensures a procedure to file grievances through the JEP, Weaver believes the confidential hotline available to workers holds little power to enact change in comparison with the better-equipped and more responsive union grievance process.

“The union’s job is to go to bat for workers when they come forward with a complaint,” Weaver said. “People whose employer is Georgetown just are in a different situation when it comes to taking the side of a worker versus Georgetown.”

The grievance process is by no means perfect, though, with workers continuing to report many more instances of the racial discrimination that led the workers to unionize in the first place. According to Charlene Grant, one of the the shop stewards at Leo’s, managers’ preferential treatment creates racial tensions among employees. Grant described hostile work conditions for African American workers at predominantly Latino work stations, like the pizza station and the catering services.

“The management tries to divide us and I really don’t like it,” Grant said. “They try to divide and conquer us.”

While Cutler did not address any instances of such behavior in order to avoid violating “the integrity of the bargaining process with the union,” she said that Aramark does not tolerate bias or harassment of any kind.

The university maintains regular contact with Aramark managers to address issues of food quality, a major source of dissatisfaction among students. According to Sam Greco (SFS ’15), Georgetown University Student Association director of auxiliary service initiatives, GUSA engages in weekly discussions with Georgetown administrators and Aramark managers to find affordable solutions. While workers do not participate in these conversations, their opinions on food quality are no different from the popular student perspective.

“I don’t think it’s any secret to anyone who’s eaten at the dining hall that there are serious flaws, and we look to address those,” Greco said.

“I don’t think it’s any secret to anyone who’s eaten at the dining hall that there are serious flaws, and we look to address those,” Greco said.

According to Piner, who now works as a prep cook at the salad bar, employees bring their own food to work regularly in order to avoid the dining hall’s limited options and poor quality.

“It’s so bad, the employees don’t even want to eat it,” Piner said.

While Greco agrees that the food quality is problematic, he said that continuous conversations with management have yielded results, citing the return of the wok station after the summer holidays. Greco also said, however, that the interpersonal service at the dining hall stands at an unacceptable quality level.

“While we make sure that our workers are compensated to a fair living wage that coincides with our Jesuit Catholic values, I am also adamant that every student should expect to be greeted, should expect urgency, eye contact, smiling, thanking—the common things that we expect of any hospitality employee,” Greco said.

Such a demand becomes harder to meet for some workers, for whom the toll of working conditions is hard to bear.

“It’s hard to have a smile on your face and continue to be friendly. A lot of times we’ve got a lot of anger, and a lot of stuff going on with us. And it’s hard because sometimes we might take it out on y’all. But we really don’t mean to,” one worker who has been working at Leo’s for 12 years told the Voice on condition of anonymity before breaking into tears. Last week, a manager told the source that workers were expected to act as robots.

“We’re not robots, though. We’re humans,” the source said.

Aramark representatives were unable to comment on this allegation due to the ongoing negotiations.

While Weaver said that GSC is proud of Georgetown’s JEP tool for fighting workplace inequality on campus, they acknowledge it is not as strong “as it could or should be,” yielding unjust situations that lay within the letter of the law. “The university works closely with vendors on compliance and is in regular contact should any issue arise,” Pugh wrote in an email to the Voice.

“If Georgetown is not violating the contract and yet all these bad things are happening, it shines a light on some issues GSC has been raising on how strongly the JEP can be enforced,” Weaver said.

Stemming from what GSC sees as inadequate action, students have developed a more vocal standpoint on the issues affecting workers. While GSC members regularly host worker breakfasts between the night and morning shifts every Friday, and larger events like a social at Leo’s last semester, they have developed profound relationships with workers over the years that make them aware of issues that may otherwise be delegated to the union.

In light of workplace accounts like those described and inequities in benefits and wages, GSC began to disseminate a student petition to show solidarity with the workers. As Chris Wager (SFS ’17), explained, students have an even greater imperative to act on the injustices seen at food services on campus in light of the Jesuit value of cura personalis and being women and men for others.

“The mistreatment of campus employees should be seen as unacceptable to all people at Georgetown. … I say this not only because of Georgetown’s status as a Catholic university but also for the mere fact that the dining employees are vital members of our community and should be treated as such,” Nicolette Brownstein, undersecretary of auxiliary services to GUSA, wrote in an email to the Voice.

Student solidarity, in fact, formed the impetus for many of the rights workers on campus enjoy today. GSC-led efforts that began in 2001 and included a hunger strike, for example, led to the implementation of the JEP in 2005, while petitions, small protests and a worker-student rally with attendance of over 100 students led to unionization in 2011.

GSC therefore launched a student petition on social media to demonstrate the students’ solidarity with the workers. The petition, which has garnered 1,210 signatures as of Wednesday, will be presented both to Aramark management and the Georgetown administration in coming weeks as negotiations for a renewed contract continue.

When asked to comment on hopes for negotiations, Pugh wrote that that Georgetown expects “both parties to negotiate in good faith and to reach a mutually agreeable resolution.”

During the last contract negotiations on Tuesday, Jan. 23, however, Aramark failed to make a proposal that would raise the Georgetown employees to the standard held by Aramark employees at the other D.C. universities, according to Smith.

When Geaney-Moore asked the assembled workers that previous Friday at Leo’s if they would continue to fight for better treatment, the workers provided a resounding “yes.” Before returning to their work stations, the workers turned towards the gathering of students that had accompanied them downstairs.

“We wouldn’t be here without your support,” one worker announced. His colleagues clapped and a few began to cry as they hugged some of the students who were present.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article incorrectly identified the undersecretary of auxiliary services to GUSA. Her name is Nicolette Brownstein, not Nicolette Browning. The article has been changed to reflect this correction.