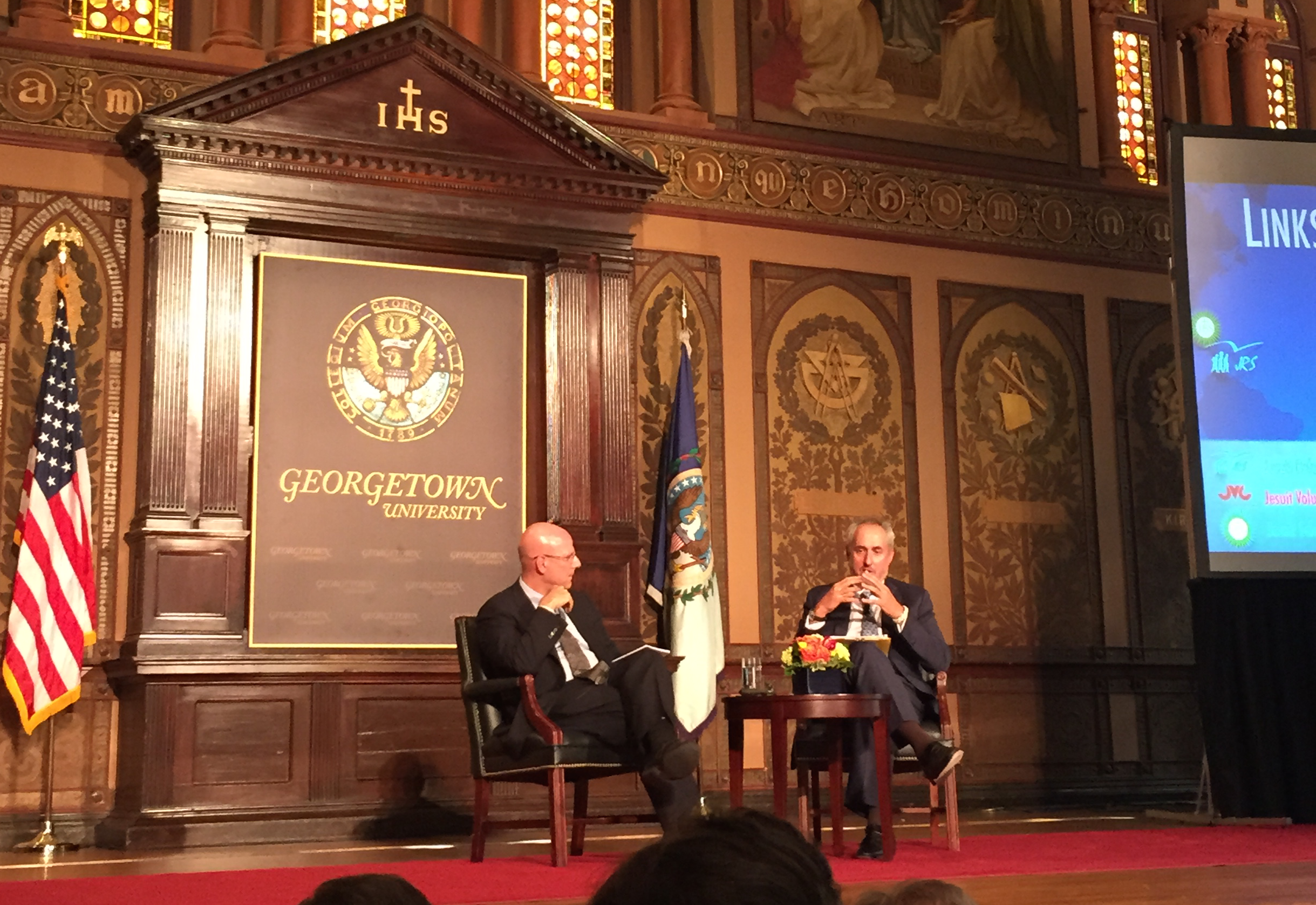

School of Foreign Service Dean Joel Hellman spoke Sept. 9 in Gaston Hall on issues of global governance and how to prepare students for solving global aid challenges. Dean Hellman’s remarks were followed by a dialogue with Stéphane Dujarric (BSFS ‘88), spokesperson for UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, and a question-and-answer session with students.

The event, entitled “Challenges to Global Governance,” was the first installment in a semester-long conversation on “The Global Future of Governance,” the second of four semesters of Georgetown’s Global Futures Initiative, a university-wide project to explore international issues through teaching, research, and dialogue with world leaders.

In his overview of global governance, Hellman emphasized the need to “rethink and remake the global governance architecture” in order to adapt to the reality of extreme global poverty and create innovative solutions for effective aid in the future.

He identified several key challenges that hinder governance in vulnerable nations, including security and development, the need for state building, undeveloped human capacity, greater risk of failure, and extended time frames for results. Hellman argued that these challenges create the need to revise the current framework for global development.

In describing the obstacles to finding global solutions to extreme poverty, he focused primarily a group of countries called “fragile states,” where poverty rates have been stable or increasing in recent years. “We classify 33 countries as fragile states based on the quality of their institutions and the extent to which there have been peacekeeping forces or active conflict,” said Hellman.

According to Hellman, these states lag behind in achieving United Nations Millennium Development Goals, a set of eight targets that all countries sought to meet by 2015. The states also contribute 84 percent of the refugees from developing countries. However, a smaller amount of development assistance goes towards these 33 fragile states than other developing countries.

Hellman also noted that a larger percentage of international development assistance goes towards Afghanistan and Iraq, which he called U.S. security concerns, than to other fragile states. He described this skewed distribution of aid as another challenge facing countries with extreme poverty.

He explained that the way donors approach aid does not take into account the nature of institutional strength and human capacity in fragile states, including conditions that create greater risk for investment and a longer time frame for results.

“We know a lot about how states function; we know very little about building states, creating states, in areas in which informal power structures, in areas and communities where the basic framework for state engagement for state bureaucracy and officialdom don’t exist,” said Hellman.

Ultimately, Hellman prioritized extending time frames for the development of state institutions as the most important step in changing the global governance paradigm for the better.

He stressed the ability of Georgetown faculty and students, particularly in the SFS, to find solutions to global problems by approaching them differently.

“One of the key things we need to think about is first how we look from various different vantage points, cultural, institutional, political, historical to think about a new way of approaching institutional development and human capacity development in these countries,” he said. He added that the international Jesuit network was another one of Georgetown’s strengths in seeking to solve problems in fragile states.

Dujarric and Hellman together discussed further issues surrounding global governance, such as the relationship between humanitarian and development aid, the conflict between military-driven and development-driven aid strategies, and the trend towards privatization of international aid seen in organizations like the Gates Foundation.

In answering a question posed by Mike Fox (MSFS ‘16), Dujarric predicted that the future of the United Nations will include more data-driven and innovative practices, better equipped to use technology to tackle the challenges Hellman described. “I think you will find by the time you get into the workforce, a much different UN,” said Dujarric, going on to describe recruitment from Silicon Valley and the recent development of a data lab to examine smartphone and Internet data from the developing world.

“The structure is changing and slowly changing,” Dujarric told Fox, “but to really change they will need people with innovative minds who are willing to take risks.”