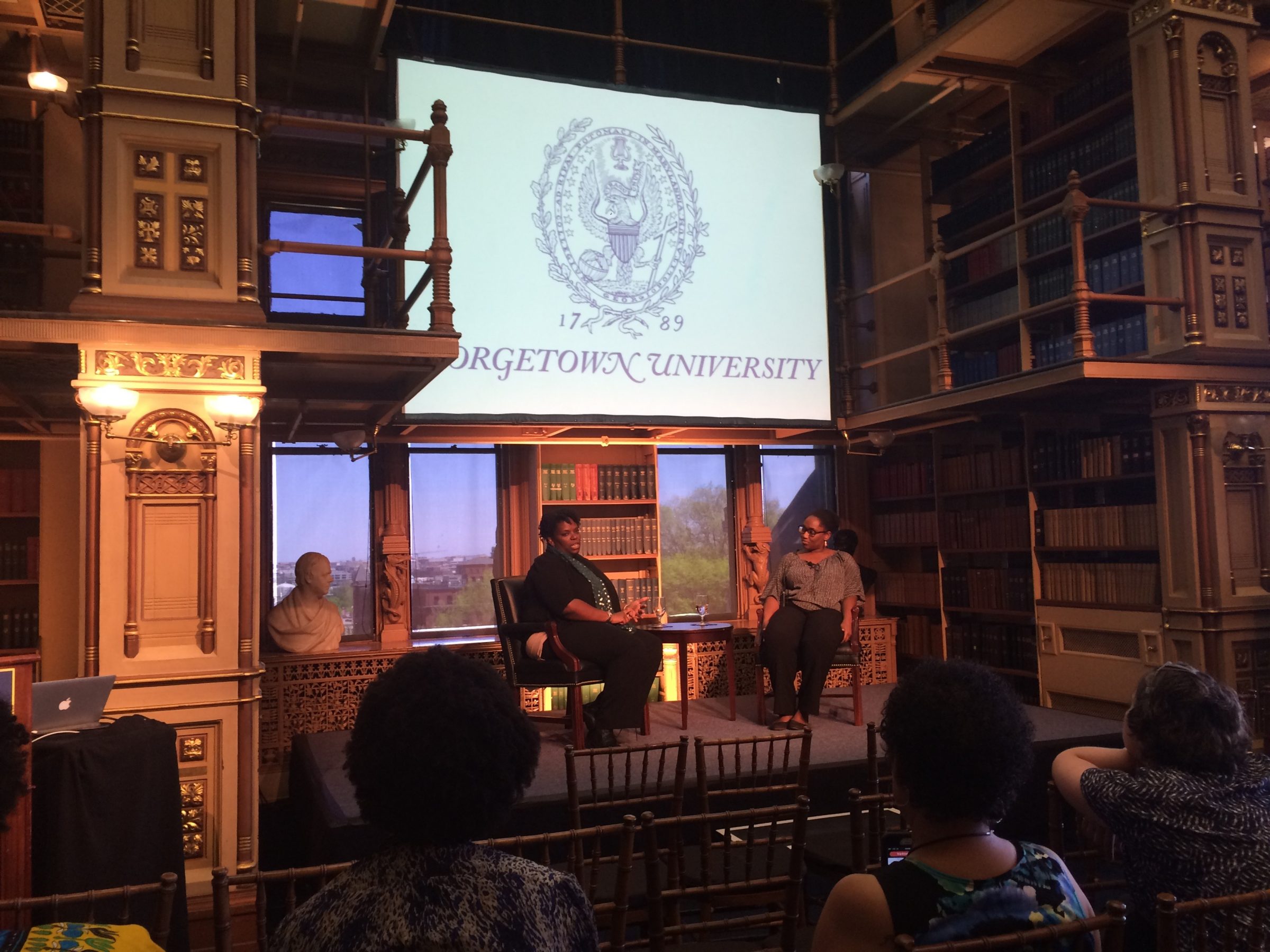

On Monday afternoon, Dr. Kimberly Juanita Brown, Assistant Professor of English and Africana Studies at Mount Holyoke College, discussed her 2015 book, The Repeating Body: Slavery’s Visual Resonance in the Contemporary in Riggs Library. The speech was part of Georgetown’s Emancipation Day symposium, which ran from April 12 to April 21. The symposium commemorated the DC Compensated Emancipation Act of 1862, which ended the practice of slavery in the District of Columbia.

The symposium itself was organized by Georgetown’s Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation, which hoped to take advantage of the anniversary to explore the history of slavery in an academic sense. “These events [of the symposium] feature perspectives from leading scholars, writers, and artists exploring the historical legacy of slavery both locally and nationally,” reads a statement on the Working Group website. An email sent from the University Office of the President on April 19 further helped to frame the symposium within the context of Georgetown’s ongoing examination of its history with slavery. “Over the course of the past year, our efforts to address the historical legacy of slavery have focused on a new digital archive of historical documents, conducting archival research on the [272] slaves and searching for their descendants, community dialogues, a Teach-In, and a week-long symposium taking place this week in honor of D.C. Emancipation Day,” the email read.

Brown’s speech discussed the danger of obscuring the human suffering of slavery with the perpetuation of the myth of black stoicism. Brown quickly presented the central question of her book, which would go on to inform the following discussion: “Why have representations of black women been resistant to the concept of the body’s inherent vulnerability?” Brown’s speech attempted to answer this question through its central thesis. “The concept of the body’s vulnerability –that it is made of flesh and bone, and that it can be broken– is still a difficult rendering in the context of slavery, gender, and representation,” she said.

Photo: Michael Coyne

Dr. Brown focused on a pronounced neglect of the vulnerability of black individuals, particularly women, in cultural works. “We think about slavery the way we think about black people in pain– infrequently,” she said. “For those of us who work on the slave system and its legacies, attempting to illustrate this pain is an exercise in frustration.”

Brown discussed at length how her this theme is expressed in Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel Beloved, inspired by the Margaret Garner case. Garner, a formerly enslaved woman, killed one of her own children when confronted with the possibility of her family’s return to slavery under the Fugitive Slave Act. At least some of Garner’s children were the product of her sexual abuse by white slave owners, though this was never explicitly acknowledged during her ensuing trial. Brown described the Garner case as indicative of systemic denial of the human suffering inherent in the institution of slavery. “This is the imagistic trace of slavery’s delineation: the imprint of both master and slave, and the willful blindness that attends a guilty nation-state built on the very bodies of the very slaves it tries desperately not to see. Beloved disallows this blindness by sprinkling the text with disparate narratives of problematic sexualization,” Brown said.

Brown denounced traditional depictions of Garner as dehumanizing. In particular, Brown criticized Thomas Satterwhite Noble’s sensationalized painting of Garner. The painting’s undoing is its excessive and exaggerated focus on “the dark and monstrous mother, her equally dark, dead, and injured children, mostly boys,” Brown said. “There is an absence of the visual possibility of previous sexual violence or exploitation–just the subtext of a slave woman with apparently inherent violent intent.” Brown added that Noble’s painting fanned the flames of demeaning stereotypes, and perpetuated the myth of the unfeeling “supremely powerful figure of black womanhood.”

Brown concluded over a haunting rendition of “Motherless Chil’” by Sweet Honey in the Rock, an all-female African-American a cappella group. The music, Brown asserted, forces listeners to “reckon with the trauma of the motherless child, as well as their natural corollary–the childless mother,” and as such emphasizes the humanity and trauma of slavery.

In a brief question and answer period, Brown was asked to offer advice to Georgetown as the university addresses history with slavery. “Slavery’s kind of everywhere. I’m constantly saying if you study slavery, you study everything; you study labor, production, reproduction, gender, race, everything is located there,” said Brown. “So I think what institutions like Georgetown can do is to have very different disciplinary frameworks [of study] to look at the same archive [of slavery and its history]. What we find together there might be a spectacular production.”