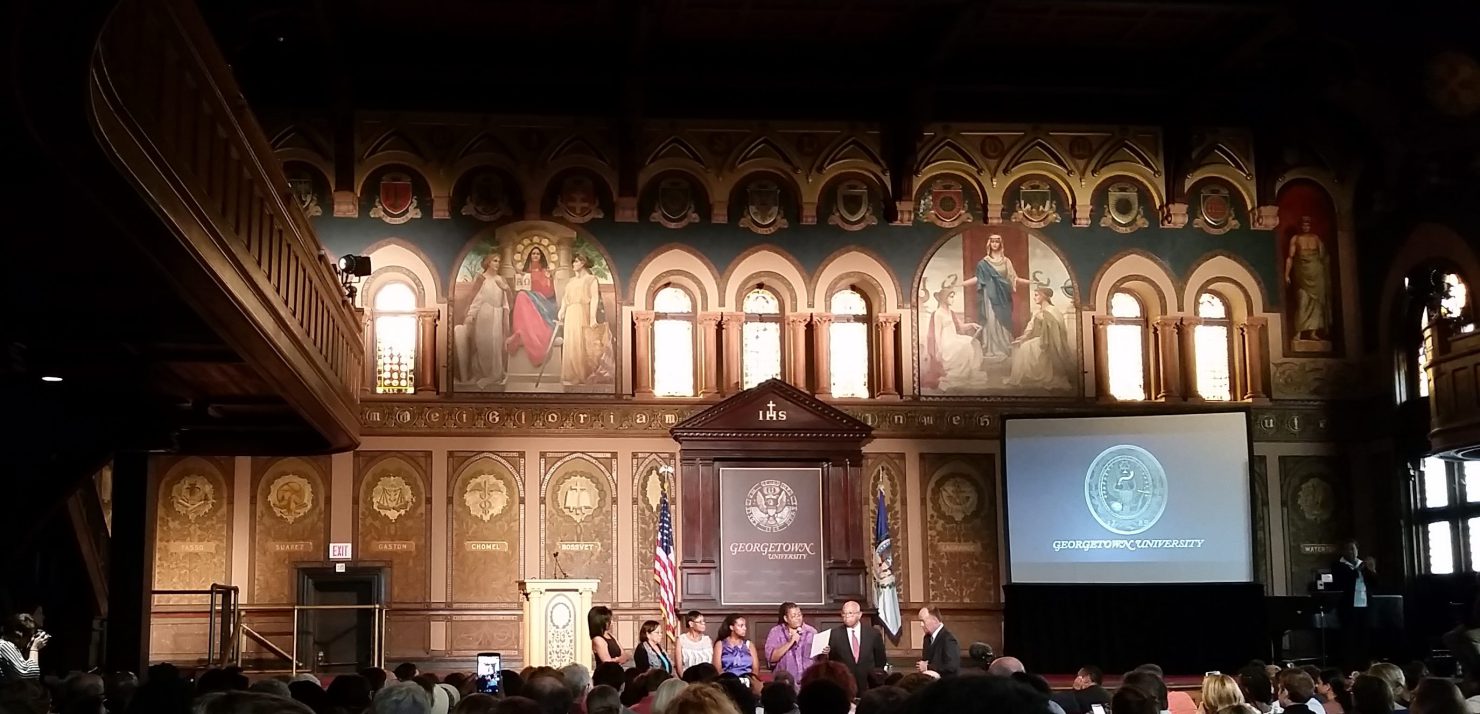

President DeGioia, in his remarks introducing the measures to be taken to atone for the University’s sale of 272 slaves, spoke of a need to “reconcile” Georgetown’s history of and participation in the institution of slavery. On campus, the sentiment I’ve picked up on thus far has been that the university has, either partially or fully, done just that. Some see the measures DeGioia announced as a first step in the eventual, more complete process of reconciliation; others, some of whom never acknowledged the need for the university to act in the first place, see them as the extent of reconciliation.

Nothing is more indicative of this second attitude than the rhetorical framing of DeGioia’s announcement, and more specifically what its details amount to.

On Friday, The Hoya ran an editorial which claimed that, “while the wounds can never be fully healed, what the university has done now is both a solid measure of progress and a firm foundation from which to work in the future.” That same day, they ran a story with the following headline: “Descendants of the 272 React to Reparations.” The Chronicle of Higher Education used that same word, “reparations,” in a story it published about DeGioia’s announcement. A Slate piece read: “Georgetown’s Reparations are to be Commended. But White Catholics Still Owe Black Americans More.” Even Ta-Nehisi Coates, author of what is perhaps the most influential argument in The Atlantic concerning reparations of the last decade, initially labeled the measures reparations.

This use of the term reparations—this mislabeling—is dangerous. Primarily, it lacks foundation in fact and historical precedent. In an enlightening, but perhaps under-circulated, piece for Vox, sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom outlined the three parts needed for a policy or action to constitute reparations: “acknowledgement, restitution, and closure.” She argues that while Georgetown has provided specific acknowledgement of its wrongdoing, it has yet to provide restitution which mirrors fully its wrongdoing, and therefore has not achieved closure. The piece, and Cottom’s argument, is insightful, cutting, and persuasive, but it did not seem to break the surface of on-campus dialogue surrounding this issue.

Most significant in this mislabeling is the equation of material loss with potential. As DeGioia noted in his remarks, Georgetown benefited—in fact, even exists as an institution to this day— directly and materially “from the sale of 272 children, women, and men.” Fact-based, historical analysis sheds light on, and gives real numbers for, the economic damage done to enslaved people in this country. Put simply, Georgetown sold and separated real people and families into work they did not choose and were not compensated for, stripped them of their human rights and dignity, and was complicit in their future exclusion from voting, legal, housing, educational, health-care based, and vocational rights.

To reconcile this reality would be to provide financial and material restitution for a financial and material crime. Preferential admissions misses this mark. It provides potential future returns for past material losses. It assumes that individuals can and will leap through the immense socio-economic loops to get the grades and scores and leadership roles to put one in the position to even be considered for admission to Georgetown. And, as Cottom points out, it fails to acknowledge the reality that income and net worth of white families without college degrees often exceeds those of black families with them. Likewise, it overlooks deep-rooted job discrimination, documented in studies that present employers with identical resumes–one, though, with a stereotypical white name and one with a stereotypical black name–who subsequently choose the white name resume. Reparations acknowledges and seeks to address founded economic disparities with mechanisms of economic alleviation. Reparations provides scholarships, vocational programs, grants for books, tutoring, and debt-relief for the 272 descendants.

But to call what Georgetown did reparations isn’t just intellectually and factually lazy (or dishonest); it’s rhetorically dangerous. It sets a precedent for the use of “reparations” in a context lacking material solutions; it lowers the bar for an actual conversation this country needs to have about what it owes those whose backs we built and continue to build this country on; it diminishes and denies the undeniable, ubiquitous damage done—in forced labor centuries ago and in segregation, incarceration, and denial of access to education, housing, and health care today—to black people and communities in this nation.

I happen to think it hasn’t, but whether or not Georgetown has reconciled its past with these current steps is a conversation we can have. In the meantime, though, let’s be careful to use rhetoric and language of moral and intellectual honesty. Let’s not denigrate one of the most powerful concepts related to race relations as we seek to resolve and reconcile our own.