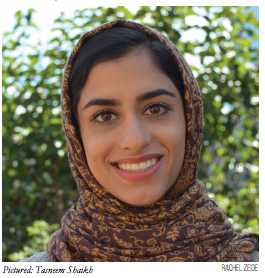

Tasneem Shaikh (COL ’17) wants to become a doctor. To that end, she is pre-med, and is planning for the future with a mixture of excitement and uncertainty that most seniors would recognize. If you met her, you would also notice that she wears hijab, recently favoring a turban-style headscarf with which she can wear earrings.

In this time of rising anti-Muslim sentiment, the Voice spoke with a few of the women who wear hijab at Georgetown to get an idea of how this practice factors into their experiences here. Each of them stressed that the practice of hijab can hold a different meaning for every hijabi.

Shaikh considers hijab a crucial component of her life and faith. “For me, it’s an essential part of my identity. For me, the hijab, it’s my way of worshipping God and it’s also my way of representing Islam and it’s a very evident reminder of what’s important to me in my life and my spirituality. And so by that I kind of mean, it’s every single moment of my life, this is what I’m wearing, this is what I’m choosing to do,” she said.

She is happy to talk about hijab, provided those asking are respectful, which she finds to be the case most of the time.

“It’s something that I’m proud of, and I can be proud of for myself for wearing this. And so, sharing that with others who are seeking knowledge or are seeking more about it is something that I’m always willing to do and am proud to do,” she said.

Khadija Mohamud (SFS ’17) is the current president of the Georgetown Muslim Students Association. Hijab plays an important role in her life, although she finds it difficult to define its meaning in concrete terms.

“My definition of what hijab means changes every day, because it depends on the context and my intention,” she said. “So, part of hijab is, it’s not necessarily just wearing the headscarf itself, it’s the idea that I’m going to conduct myself publicly as a Muslim, so that means that I have to be cognitively aware of what I’m saying, how I’m interacting with people … it’s publicly saying that I’m Muslim. So before I even interact with you, you are relatively aware that I’m Muslim unless you’ve never seen a Muslim before.”

While she is wary of trying to speak for either hijabis or Muslims as a whole, she finds this is a role into which she is often cast.

“That’s a burden that I think that hijabis will always have to deal with, and especially now more than ever, it’s immense, how huge that burden is, because you walk into a classroom, you walk into an interview, you walk into anywhere on campus, people already assume that you are carrying Islam everywhere that you go, and that you can speak for the entire religious community, which is not in any case correct,” she said.

“When we wear hijab, it’s the most easily identifiable marker of your faith as a Muslim,” said Kristin Sekerci, a program coordinator at Georgetown’s Bridge Initiative, a research project sponsored by the Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding aimed at pushing back against Islamophobia. Sekerci is one of the dozens of hijabis who work and study on Georgetown’s campus, covering her hair with the headscarf worn by many, but not all, Muslim women.

For Shaikh, the university has proven itself hospitable, and its openness to spirituality factored into her decision on where to go to college.

“It was one of the reasons I chose [Georgetown]. It’s been one of the most welcoming and encouraging universities and communities … I think by having that kind of standard for itself, its community is automatically selected for people who are very welcoming, so individually as a person who wears hijab, and I’m very represented by my religion in my choice of hijab, I’ve never had an issue. Everyone treats me, basically, how I want to be treated,” she said.

Sekerci also described the Georgetown community’s treatment of its hijabi members in positive terms.

Sekerci also described the Georgetown community’s treatment of its hijabi members in positive terms.

“I’ve had no bad experiences on campus,” she said. “And the fact that it’s a Catholic, Jesuit community just makes it even more special. Because there’s the interfaith element, and there’s such a welcoming ethos. And where I work, the Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding, the fact that it even exists … I think is case in point, on how welcoming and receptive the community’s been.”

Mohamud echoed these sentiments.

“I haven’t faced any hostilities. There are times when you get stares every now and then,” she said. “For the most part, it’s a very friendly and accepting environment.”

For Shaikh, who had attended an Islamic school in Virginia prior to coming to Georgetown, and therefore was uncertain how her peers in school would act around her, the reactions of her fellow students were especially encouraging.

“Especially when it comes to kids, I’m always kind of scared that people won’t be as chill, or they might have a certain kind of formality when it comes to talking to me or anything like that, but seeing people just be normal … it surprised me even more,” she said.

This is not to say that Georgetown has no work left to do to improve its attitudes toward hijabis. Mohamud spoke of feeling that she must sometimes represent Islam in a classroom environment when a professor makes an ignorant comment.

“You feel like you constantly have to defend your faith, but you feel like you have to defend your faith in the most random places,” she said. “Sometimes you have professors, who are very well-educated scholars and pundits, saying things that are profoundly ignorant in terms of what they understand of Islam. Then you, in a lecture of 200 people, you feel compelled to say something about it. And it can be nerve-wracking, just like anyone else having to speak out in front of a large crowd, but it’s more nerve-wracking knowing that when you leave that seminar or that classroom, that lecture, your classmates are going to leave thinking that this is what Islam is.”

Shaikh mentioned similar frustrations, and feeling that some professors find it surprising that she can offer intelligent and insightful contributions to a classroom environment.

Shaikh mentioned similar frustrations, and feeling that some professors find it surprising that she can offer intelligent and insightful contributions to a classroom environment.

“Sometimes [people] can already have perceived notions about who you are or how smart you are. There are certain professors who if I say something very intelligent, they’ll have preconceived notions. Sometimes people think that people who wear hijab are more sheltered, they’re very shy, not so outgoing,” she said. “There are these stereotypes that go along with the hijab. I think every hijabi has experienced making someone surprised by saying something smart, or being more outgoing.”

Still, she emphasized that, while there are some challenging moments, the experience has been a positive one.

“But overall, the Georgetown community has been very welcoming, and I’ve never really had much of an issue,” she said.

If things are largely good for hijabis at Georgetown, the wider picture of religious tolerance in America is more muddled. This presidential election season has seen the rise of some virulent anti-Muslim rhetoric in the national conversation, one of the most striking examples being Republican nominee Donald Trump’s call for a temporary shutdown on Muslims entering the United States.

“Anti-Muslim sentiment has been out there for a while now, of course. Ever since 9/11 is really when it spiked, of course. But a lot of that really nasty rhetoric has been part of the far right movement or alt-right, and folks in that camp, and it’s the kind of thing that is impolite to say in polite conversation or at dinner tables. But now with our Republican nominee, he says it so openly, and with such gravitas, that it’s considered acceptable conversation now in the public,” Sekerci said.

Today, fear can occupy the minds of the women interviewed for this piece. Both Mohamud and Shaikh described the terrified reactions of their parents to a 2015 incident in which a Muslim woman was pushed in front of a London subway train.

“I remember after that my whole family texting me, or calling me and messaging and being like, ‘Be careful in the streets. Don’t be alone.’ My father was so worried about me,” Shaikh said. “You never know what people may think of you or how they may perceive you. And being so publicly represented, there’s always that kind of fear that’s behind all of this.”

Mohamud described the anxiety her parents felt with her commuting by train to a summer internship following that incident. “Now my parents are like, ‘If you have headphones on, make sure you take them off, or you’re not listening to anything, stand far away from the loading area for the train.’ You don’t know what’s going to happen. There is a degree of fear, to be honest,” Mohamud said.

She also remembered the confusion of watching her mother experience harassment for wearing hijab following the 9/11 World Trade Center attacks.

“I’ll never forget people giving my mom stares, I remember people throwing stuff at her sometimes,” she said. “These are things that I can’t forget, because they’re very distinct memories, and as a child you’re confused because you’re like, ‘What’s wrong, it’s my mom, why would anyone want to treat her differently because of the way she looks?”

In light of the fear she sometimes feels, Sekerci described taking a self-defense class, put on by a Muslim human rights activist, geared specifically toward teaching hijabis how to protect themselves from attacks.

“It taught you how specifically to defend against hijab attacks,” she said. “But when you step back and think about it, it’s very disturbing that we’re training ourselves to deal with that, if it ever did, God forbid, happen.”

Sekerci works to push back against Islamophobic mindsets through her work at the Bridge Initiative, and she pointed out the importance of keeping in mind the positive incidents that take place along with the negative.

“It’s important to highlight the negative, and to call that out, but it’s also really important to highlight the amazing things that people are doing within the American Muslim community, and allies outside the American Muslim community,” she said.

In both D.C. and across the country, there have been many such positive examples, and Sekerci offered several. These included the billboard unveiled last year by the American City Diner, located in North West D.C., which read, “Standing with American Muslims,” and a resolution condemning anti-Muslim sentiments, which was introduced in September to the D.C. City Council. On a national scale, such examples range from something as bureaucratic as Philadelphia’s decision to make two major Islamic feast days, Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, into city holidays, to a story as personal as a group of Southern California high school girls encouraging and propelling their hijabi friend’s successful bid for homecoming queen.

For hijabis specifically, a supportive community can arise from shared practice. Ironically, although Shaikh had attended an Islamic school while growing up in Virginia, she didn’t find this community element of practicing hijab until she arrived at college, as she was “one of the very few” students who wore hijab at her previous school.

“[It’s] surprising that, going from an Islamic school to a big university, this is the first time where I’ve got to experience having that community of girls who wear hijab just like me,” she said. “And it’s amazing, my roommates [wear hijab], and we can share headscarves, and we go through the experience and we can talk about it inways that other people wouldn’t understand. So we have that kind of mutual understanding and what it’s like to experience life, and being in America and being in a college or university as a hijabi together.”

Mohamud also spoke to the community that comes with practicing hijab.

“At Georgetown there’s a pretty large hijabi community, which is pretty awesome,” she said. “It makes you feel comfortable when you see another woman in a hijab. But it also reminds you that, at least from what I’ve learned at Georgetown, that for me to assume that all hijabis share my sense of identity, my confidence in my identity, that’s not the case. Everyone has their own perspective.”

In addition, she pointed to complexities within this community that may not be apparent to outsiders.

“Color is another dimension that isn’t mentioned when we talk about hijabis,” she said. “Where the reality is that my experience as a black Muslim woman is different than an Arab-American Muslim woman who wears hijab. It’s not the same. And even within the Muslim community it’s very different. And these are issues that our community needs to address.”

And, although hijab can inspire a tremendous sense of community, each of the women interviewed spoke of the diversity and individuality that exists within the practice of hijab. Shaikh mentioned that her own preferred style of hijab has changed throughout her life.

“Every girl wears the hijab in very different ways. So there was one year of my life where I wore a black scarf every single day. But then after that I sort of started playing with different colors and different styles. So this is the new turban style that I’ve been trying in the past year. It allows me to wear earrings, and show them off,” she said. “So hijab isn’t just a headcovering, that’s like—there’s one way of doing it, and it hides who you are as an individual.”

“Every girl wears the hijab in very different ways. So there was one year of my life where I wore a black scarf every single day. But then after that I sort of started playing with different colors and different styles. So this is the new turban style that I’ve been trying in the past year. It allows me to wear earrings, and show them off,” she said. “So hijab isn’t just a headcovering, that’s like—there’s one way of doing it, and it hides who you are as an individual.”

Mohamud echoed this, saying that practicing hijab is not even limited to those who wear a headscarf.

“My concept of hijab is one that includes my sisters who don’t wear headscarf, it includes my brothers who don’t wear a headscarf. So it’s very inclusive,” she said.

“There are so many different ways to wear hijab,” Sekerci said. “And in some ways it’s kind of interesting because it’s marked by, one country has a unique style, and another country has a unique style. There’s different trends that go on.”

For Sekerci, a Pennsylvania native who grew up in a Catholic family and then converted to Islam after learning about the faith through college courses and then later in conversations with her Turkish husband, it was natural that she would adopt the Turkish style of hijab.

Shaikh spoke of the flexibility hijab offers to a wearer when it comes to style.

“Once you open yourself to exploring your own identity while wearing hijab, you can find so many ways to be creative, there’s so many different types of styles you can go for, you know, mix and match with your outfits, there’s so many different prints,” she said. “You can make it fashionable in its own right. It’s not something that hides who you are, but you can make it into something that complements your personality and goes along with your own fashion statement.”

And, while there may exist an idea that all hijabis are somehow oppressed, this does not fall in line with what the women interviewed for this piece had to say. In fact, Shaikh and Mohamud expressed almost the exact opposite of this sentiment.

“Muslim women being able to take back the veil and reclaim it and redefine it for themselves is a huge part of their self-identification as a member of their community. And it’s a means of them reclaiming their active agency and their faith,” she said. “Because in the Koran we know that Muslim men and women were created as spiritually equal beings.”

“It’s a means of liberation because, in the end, it’s our choice. I was not forced to do this,” Shaikh said. The key, for her, is choice. “If you want to uncover yourself, then you are liberated by having the choice to do so, but if you want to cover yourself, you are liberated by having the choice to cover yourself as well.”

In Mohamud’s mind, this is a perspective that Western feminists need to keep in mind as they seek to include Muslim women.

“For Muslim women, we’re entering the conversation of feminism, but unfortunately we’re being introduced as, ‘Oh, as feminists in the West we need to save our Muslim sisters who are forced to wear, you know, these headscarves.’ In some cases, women are forced to wear hijab, which I don’t agree with. It’s completely something that’s up to the individual, in my belief and my faith,” she said.

Mohamud, a Silver Spring, Md. native, reflected that hijab has played an important role in her understanding of her identity as an American.

“For me, I guess, hijab is a huge part of my identity,” she said. “In terms of me discovering who I am as an American, when I started wearing hijab, that was a huge [factor], it was a major recognition of its synthesis in my identity.”

Yet, in this time of rising hostility to Islam, each of the women interviewed for this article recounted sometimes having to take an extra step to affirm their American identity to others. In sometimes subtle ways, Sekerci has also noticed that others might assign her outsider status since she began wearing hijab.

“Once you identify yourself with some kind of marker [as a Muslim], people’s perceptions of you change. When I started covering, immediately people started asking, ‘Where are you from?” she said. “And not just, ‘Where are you from?’ but ‘Where are your parents from?’ ‘Where are you really from?’ I’ve even gotten a few, ‘You speak English so well.’ and I’m like, ‘Thanks, I think I should.’ In the greater scheme of things, those aren’t really significant, but they add up.”

Mohamud spoke of the need to affirm her status as an American while defending her faith being a defining force in her life as she grew up in the post-9/11 United States.

“For me, as an American Muslim, it’s a burden that I think is very unique and think it’s a burden that I don’t know what I would be without it, because I grew up with it,” she said. “So I grew up with this idea that I’m an American Muslim, I feel more obligated, and it’s more required of me to really engage the people I can tell have never met a Muslim, and make sure that they leave that interaction knowing that American Muslims are just like anyone else. We’re American.”

Shaikh told of a time when, while walking on the streets of D.C. with a group of hijab-wearing friends, a man began yelling “ignorant, bigoted things” at them. At one point, the man told them to “go home.” For Shaikh, this was nonsensical.

“This is my home,” she said. “I was born and raised here in America in D.C., so if he’s telling me to go home, where am I supposed to go?”