“Hung Liu in Print,” the latest featured exhibit from the National Museum for Women in the Arts, is pensive, meditative. It displays a number of Hung’s prints and tapestries, all of which commemorate and elevate the most frequently ignored figures in Chinese history: women. Using her signature layered style, Hung shows viewers the perseverance and majesty of China’s women, whether they are prostitutes, laborers, or simply sisters.

Born in 1948, Hung draws inspiration largely from her experiences growing up in rural China, where she worked as an agricultural laborer during the height of the Cultural Revolution. During her time working in China, Hung acquired a deep understanding of the hardship and sorrow that Chinese women have endured historically and continue to experience today. When she could find time outside of work, Hung practiced art as often as she could, and she quickly tired of agricultural toil. In 1984, after years of hard labor in rice fields, Hung left China for San Diego, where she was able to hone her lifelong interest in art by studying at the University of California, San Diego. Despite emigrating, her youth in China remains the bedrock of her work, and she is able to both honor and elevate China’s history through her insightful prints.

Hung’s work touches on a number of elements in Chinese history, including footbinding, the legacy of courtesans, and the toil of women in agriculture. In her series “Seven Poses,” Hung displays a diverse array of prostitutes whose images hail from historic photographs and who sit either alone or in pairs, staring invitingly at the viewer. Though Hung recreates the portraits with realistic depth, the women are surrounded by animals and flowers depicted in the traditional two-dimensional Chinese style. This juxtaposition, combined with Hung’s use of floating circles—a reference to the Chinese calligraphic marking for the end of a sentence—creates a layered effect that brings these often-forgotten Chinese women into dynamic detail for the viewer.

In another historically charged print titled “Winter Blossom,” Hung honors Zhen Fei, a 19th century woman known not only as mistress to the emperor, but as an active political influencer in the emperor’s court. In the woodblock print, Zhen poses regally in traditional court attire, her face framed by a cherry blossom branch. Hung incorporates an idiosyncratic twist to the piece: dark lines all but drip down the print, making it look as if Zhen is peering through a curtain of dark rain and adding an air of mystery to her stare.

This motif of dripping, runny lines is common in Hung’s prints. She sometimes achieves this effect by pouring acid on the piece, and other times uses special printmaking techniques that she developed through continual experimentation and work with master printmakers. The lines incorporate an element of darkness to her works, conjuring images of tears and sweat that surround and cover the women she depicts. In the “Seven Poses” series, the lines disturb what would otherwise be a crisp rendering of the courtesans, suggesting that there is perhaps a darker truth behind the flowers and colorful robes. Similarly, in her large-scale tapestry titled “Rainmaker” that dominates the exhibit space, Hung expertly manipulates the threads to cover her subject: a young girl with dragonflies dancing in her hair during a gray, dreary rain shower. At close range, the thread work is seemingly random, but, at scale, the minute stitches cast the girl and her waterlogged surroundings in stunning detail.

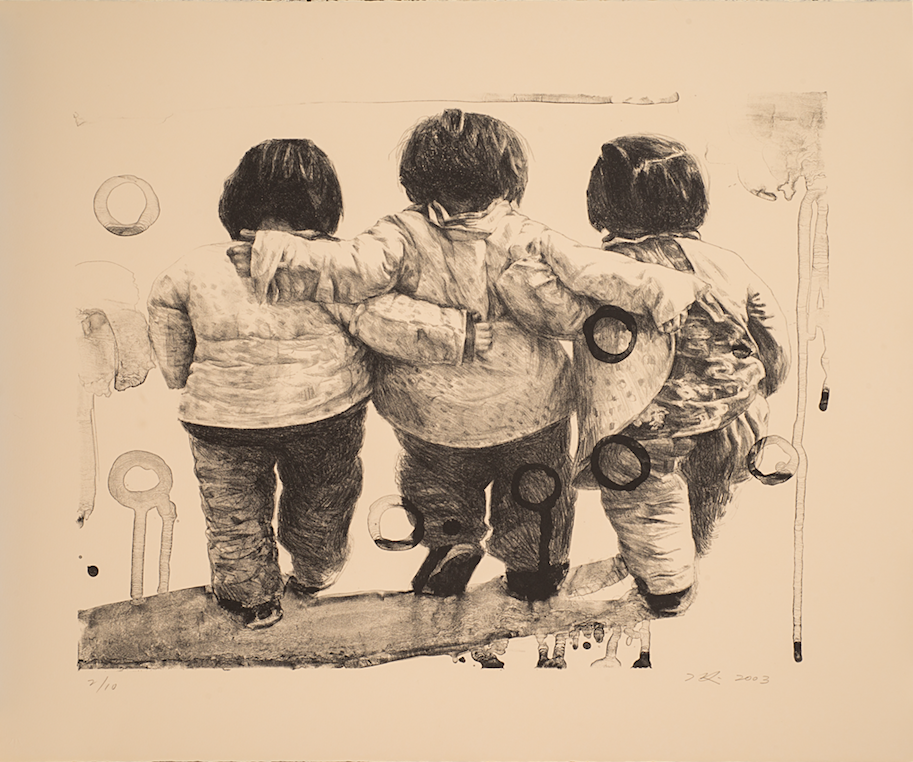

Hung uses the drips effectively in her diptych “Women in Arms I” and “Women in Arms II” to show the plight of the typical Chinese woman during the Cultural Revolution. Printed in dramatic black and white, both lithographs show three women arm in arm, one as children with their backs to the viewer and the other as adults, harrowed by war and hardship. The young girls seem to skip away from the viewer, blissfully ignorant of their unforeseeable yet inevitable experiences with adversity. Fast-forward to adulthood and the women stand in uniform with expressions of anger, sorrow, and exhaustion, looking toward something haunting that the viewer can only guess. Both trios are speckled with those same sentence-ending circles that Hung uses in her other works, but, in striking contrast, the older women are heavily smattered with black ink that looks like dripping blood.

In a piece charged with a similar social commentary, Hung shows two workers—a mother and daughter—bent over double and pulling an unseen boat by ropes tied around their waists. The print, “Mu Nu/Yellow River,” is executed in an ethereal style, with blotches of gray and soft red floating around the women in a manner akin to watercolor. These blotches, accompanied by more of Hung’s stylistic drippings, again make reference to the sweat, grief, and oppression of proletarian women. The women’s position, bent with their hands almost touching the ground, recalls images of a work animal pulling a plow, a further commentary on the degradation of Chinese workers.

Hung’s work acts in many ways as commemoration and celebration of Chinese women, all of whom she depicts in a style that is simultaneously sensitive to tradition and refreshingly creative. Her work, from the style to the subject matter, forces the viewer to redefine their understanding of printmaking. Ultimately, through her dynamic visual portrayal of Chinese women, Hung communicates to the viewers a firm stance regarding the Chinese women of history: they are not to be forgotten.