There’s no understating the importance of recruiting in college athletics, particularly when it comes to retaining touted high school athletes in-state. That’s for a pair of reasons. First, as has always been the case in high-revenue sports like football and basketball, a recruit’s commitment usually doesn’t affect just one school. Oftentimes, they’ll sign with a school in the same conference as a rival who lost out on that athlete, so the effect of winning or losing that recruiting battle is compounded. Considering this, it comes as no surprise that being able to sign a good chunk of the elite in-state high school talent in a given year is one of the most sustainable ways to build a winning program that can win championships, galvanize school spirit among students and alumni, and generate revenue to fund other sports.

Dr. Gary Green, a human behavior expert who’s worked as a consultant for over ten college football teams and dozens of other athletic programs, believes recruiting close-to-home may be even more important than ever in the next year or two. Green said in a recent interview with The Athletic: “Before 9/11, many recruits were looking to leave their home states because their parents were very structured and they wanted some distance. After 9/11, what we saw was recruits wanting to stay closer to their home state. And we’re seeing the exact same trend now. So I tell coaches now, if you’re recruiting, you should be recruiting within a radius of an eight-to 10-hour drive.”

That’s a really interesting insight from a man who follows these patterns as closely as anyone. And the best example of Dr. Green’s assertion is right at the top of the 2021 recruiting class – Korey Foreman, a defensive end from Corona, California. A former Clemson commit, Foreman backed off his decision in April, saying he felt uncomfortable with Dabo Swinney’s policy of not letting committed players take visits to other schools, which Foreman was likely looking into because of the pandemic. Foreman is now considered a lean to USC, which is less than an hour from Corona.

If COVID-19 does indeed keep more recruits closer to home, we should be able to single out schools poised to benefit from this potential shift, and others who might lose out. That’s exactly what this article aims to do by pointing out those schools with inherent geographic advantages in recruiting, analyzing which teams have successfully courted in-state talent, and finding out what’s changed in the national recruiting landscape in the last decade.

For our data, I’ll be using 247Sports’ Top 300 Composite Player Rankings from 2008, 2009, 2013, 2014, 2018, and 2019 to give a nice large sample size that paints a well-rounded picture of recruiting in the modern era of college football.

Wading In: A Macro View

It’s often mentioned offhand by college football pundits that recruiting has become “a nationwide operation” in the last few years. In 2005, a star recruit on the west coast would simply be assumed to be heading to a Pac-10 school, and might not hear much at all from SEC or Big Ten teams. Nowadays, as I like to point out, Nick Saban’s last juggernaut offense was built around a Hawaiian quarterback (Tua Tagovailoa), a Californian running back (Najee Harris), and a top receiver from Florida (Jerry Jeudy).

To confirm this notion, we can look at the rates at which Top 300 players from states with one or more Power 5 schools are staying in-state for college. In the 2008 recruiting cycle, 151 of 295 players stayed in-state, a 51.2% clip. In 2019, however, that number was all the way down at 32.5%. The stay rate for top 300 players had been almost cut in half in 2019, a seismic change from 2008, but that was in a pre-COVID world. If Green’s assertion is correct, the schools that have still been pulling in their blue-chip in-state talent throughout the last decade will be poised to capitalize – programs that have been pursuing a more national strategy might have to change their philosophies.

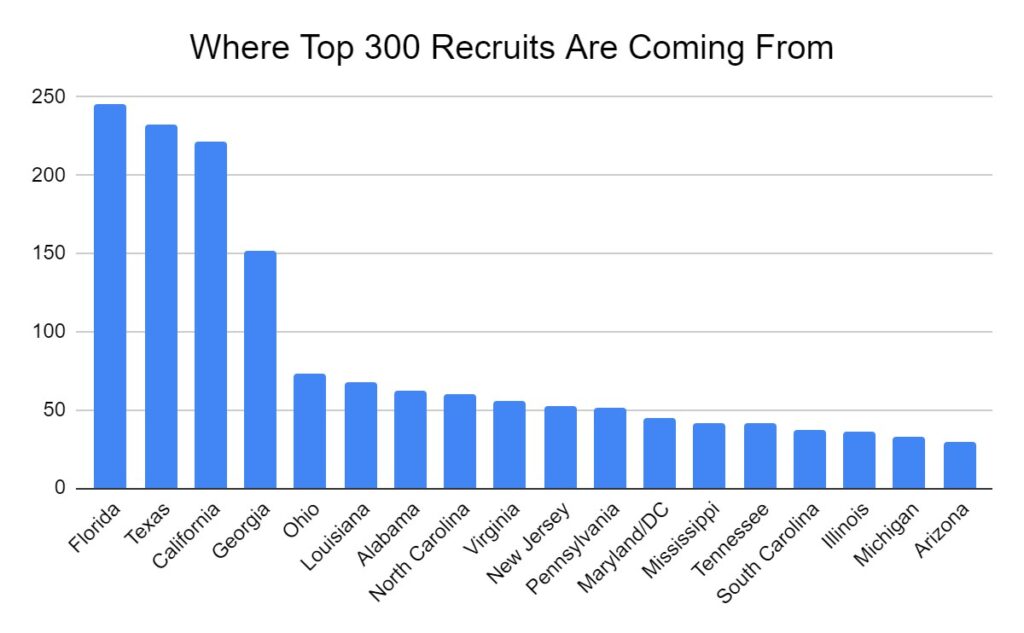

For a jumping-off point, it’ll be valuable to see which states have produced the most Top 300 recruits in the last decade. Unsurprisingly, Florida, Texas, and California lead the way, not only because of their relatively massive populations but also because of the climate and demographics of those states. They’ll always be at the top of these types of lists, and there’s a quite steep dropoff after that Big 3. Notably, though, Georgia, in fourth, has more than double the amount of Top 300 recruits of our fifth-place state, Ohio. The Peach State is a total hotbed as well.

For a jumping-off point, it’ll be valuable to see which states have produced the most Top 300 recruits in the last decade. Unsurprisingly, Florida, Texas, and California lead the way, not only because of their relatively massive populations but also because of the climate and demographics of those states. They’ll always be at the top of these types of lists, and there’s a quite steep dropoff after that Big 3. Notably, though, Georgia, in fourth, has more than double the amount of Top 300 recruits of our fifth-place state, Ohio. The Peach State is a total hotbed as well.

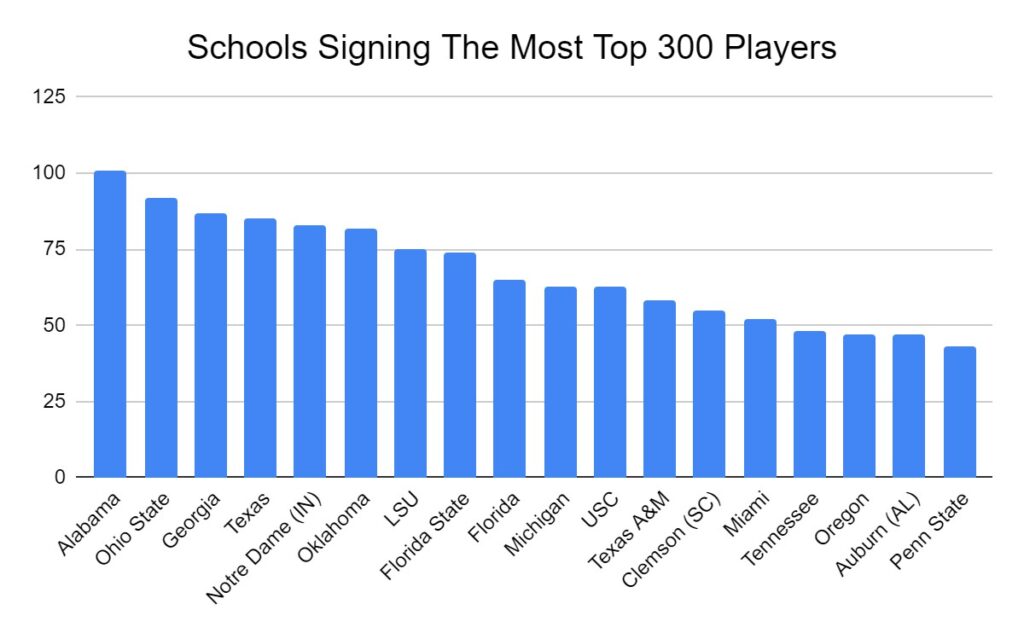

And to jog our memories on who has dominated the recruiting scene in the last 12 years, I’ll attach a chart of which programs have recruited the most Top 300 talent across these six classes. Again, there’s no real surprises – these are the names that, more or less, have produced in the win/loss column in large part because of their success on the recruiting trail. Among schools whose results have been ho-hum considering their recruiting efforts, Texas, USC, and Miami jump off of the page. Meanwhile, Clemson has significantly outperformed their recruiting results, though the Tigers have been recruiting at a top-five level in the last few years.

And to jog our memories on who has dominated the recruiting scene in the last 12 years, I’ll attach a chart of which programs have recruited the most Top 300 talent across these six classes. Again, there’s no real surprises – these are the names that, more or less, have produced in the win/loss column in large part because of their success on the recruiting trail. Among schools whose results have been ho-hum considering their recruiting efforts, Texas, USC, and Miami jump off of the page. Meanwhile, Clemson has significantly outperformed their recruiting results, though the Tigers have been recruiting at a top-five level in the last few years.

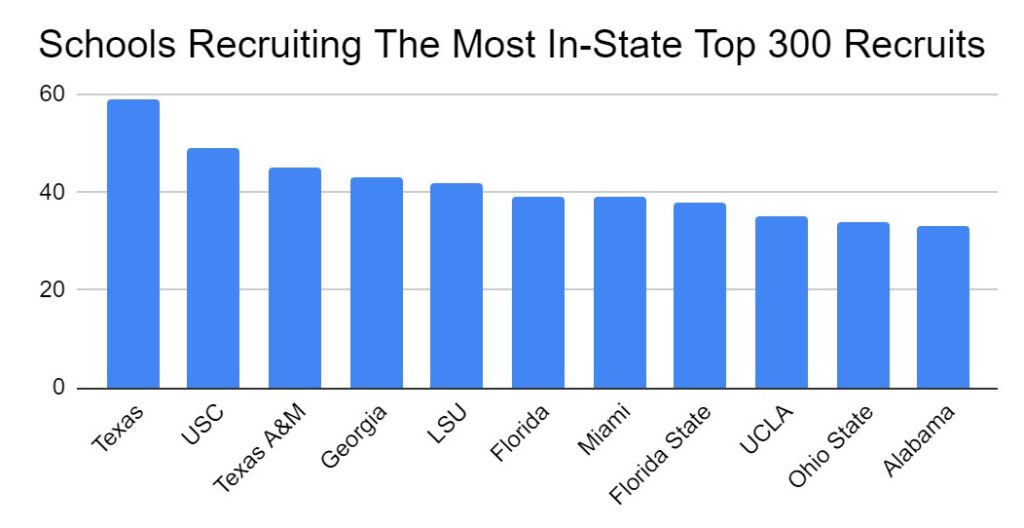

Finally, in a combination of those two charts above, it’s relevant to look at which programs have recruited the most in-state Top 300s. This is certainly not a locked-in prediction of which teams will be recruiting the best in a post-pandemic universe, as I’ll explain below. Texas, USC, and Texas A&M have excelled, though none have been terrific on the field – their high marks are largely a function of simply how many Top 300s their home states produce. And Georgia, who has been the best among those schools, has actually produced somewhat disappointing in-state results considering their only in-state competition for nearby talent is Georgia Tech. Again, that’s not the end of the story, as Georgia has recruited quite well overall. Finally, considering the smaller volume of Top 300 recruits from Louisiana, I’d single out LSU as having the most impressive in-state results among its peers (though LSU is the only Power 5 school in Louisiana).

Finally, in a combination of those two charts above, it’s relevant to look at which programs have recruited the most in-state Top 300s. This is certainly not a locked-in prediction of which teams will be recruiting the best in a post-pandemic universe, as I’ll explain below. Texas, USC, and Texas A&M have excelled, though none have been terrific on the field – their high marks are largely a function of simply how many Top 300s their home states produce. And Georgia, who has been the best among those schools, has actually produced somewhat disappointing in-state results considering their only in-state competition for nearby talent is Georgia Tech. Again, that’s not the end of the story, as Georgia has recruited quite well overall. Finally, considering the smaller volume of Top 300 recruits from Louisiana, I’d single out LSU as having the most impressive in-state results among its peers (though LSU is the only Power 5 school in Louisiana).

State-By-State Results and What’s Changed Between 2008-2019

Before we dive deeper, as I’ve alluded to, many of the best teams in college football haven’t produced exceptional in-state recruiting results. Georgia is an example, as is Clemson, which has signed fewer in-state Top 300s than the University of South Carolina. That’s a byproduct of the shift in focus from these schools to a more national recruiting strategy doesn’t place as great a priority on in-state recruits. Take the state of Alabama, which produced 20 Top 300s in the 2008-09 and 2018-19 recruiting cycles. Nick Saban’s Crimson Tide secured a stunning 16 of those 20 recruits in 2008-09, but only four of the 20 in 2018-19. I tend not to question these schools given their ridiculous results – ask a college football coach the teams they’d expect to dominate in the 2020s, and Georgia, Clemson, and Alabama might be the first three teams they mention. Kirby Smart, Swinney, and Saban can obviously to navigate shifts in recruits’ preferences with minimal dropoff in their class’ final recruiting ranking.

Now I’ll introduce the Big 3, states producing enough Top 300 recruits to nearly single handedly sustain multiple in-state giants.

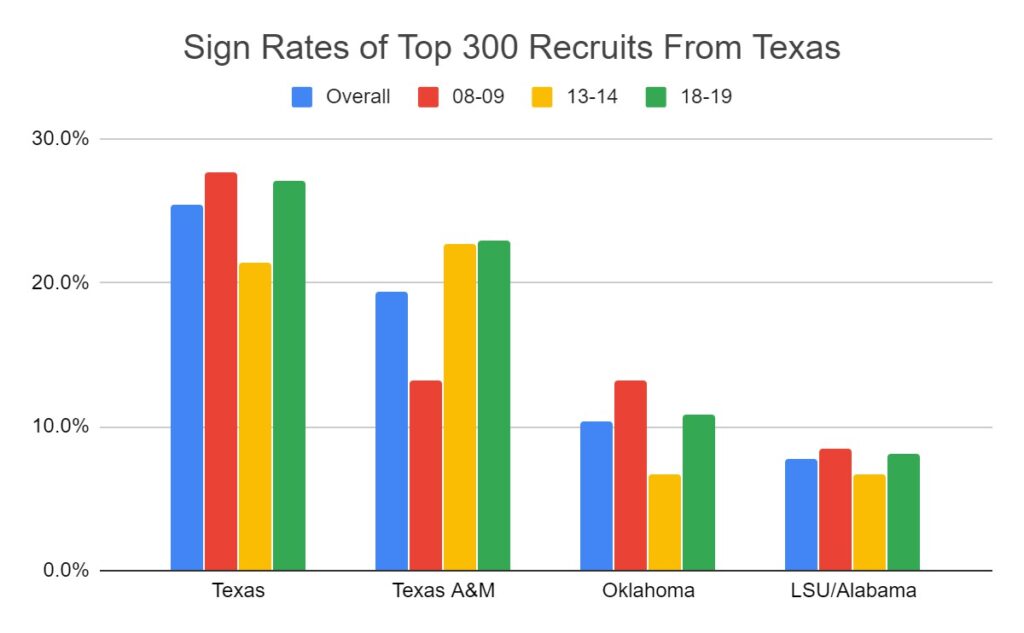

Texas

I’d call Texas an easy-to-medium difficulty of in-state recruiting for the state’s two biggest names, Texas and Texas A&M. There are three other Power 5 teams in Texas – Baylor, TCU, and Texas Tech – who have all been non-factors in the race for the states’ top recruits, each signing less than 10 total Top 300s across the six recruiting classes. Oklahoma is Texas and Texas A&M’s biggest rival for elite in-state talent, and that will only continue considering the Sooners’ three consecutive College Football Playoff appearances. Still, even if the on-field results haven’t always been there, the Longhorns and Aggies have performed admirably in-state.

I’d call Texas an easy-to-medium difficulty of in-state recruiting for the state’s two biggest names, Texas and Texas A&M. There are three other Power 5 teams in Texas – Baylor, TCU, and Texas Tech – who have all been non-factors in the race for the states’ top recruits, each signing less than 10 total Top 300s across the six recruiting classes. Oklahoma is Texas and Texas A&M’s biggest rival for elite in-state talent, and that will only continue considering the Sooners’ three consecutive College Football Playoff appearances. Still, even if the on-field results haven’t always been there, the Longhorns and Aggies have performed admirably in-state.

California

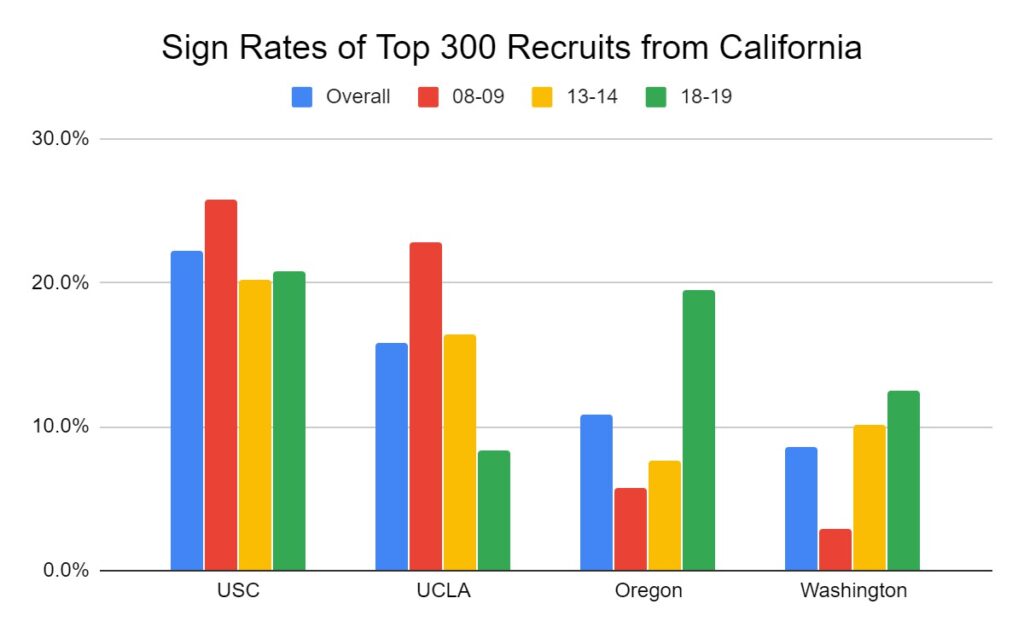

California has four Power 5 programs, but like in Texas, two top dogs have crowded out the other schools. However, there are worrying trends on the horizon, as Pac-12 rivals Oregon and Washington have gained increasing footholds in California. UCLA’s recruiting has fallen off of a cliff amid program instability, while USC had a disastrous 2020 recruiting cycle (2020 wasn’t included in the data set) due to the uncertainty surrounding Clay Helton’s future with the Trojans. Notably, the #2 overall recruit in the country in 2019, Kayvon Thibodeaux, signed with Oregon, while 2020’s top prize Bryce Young decided to ply his trade at Alabama. Considering their programs’ natural recruiting advantages in Los Angeles, USC and UCLA haven’t been getting it done. However, the pandemic could help both.

Florida

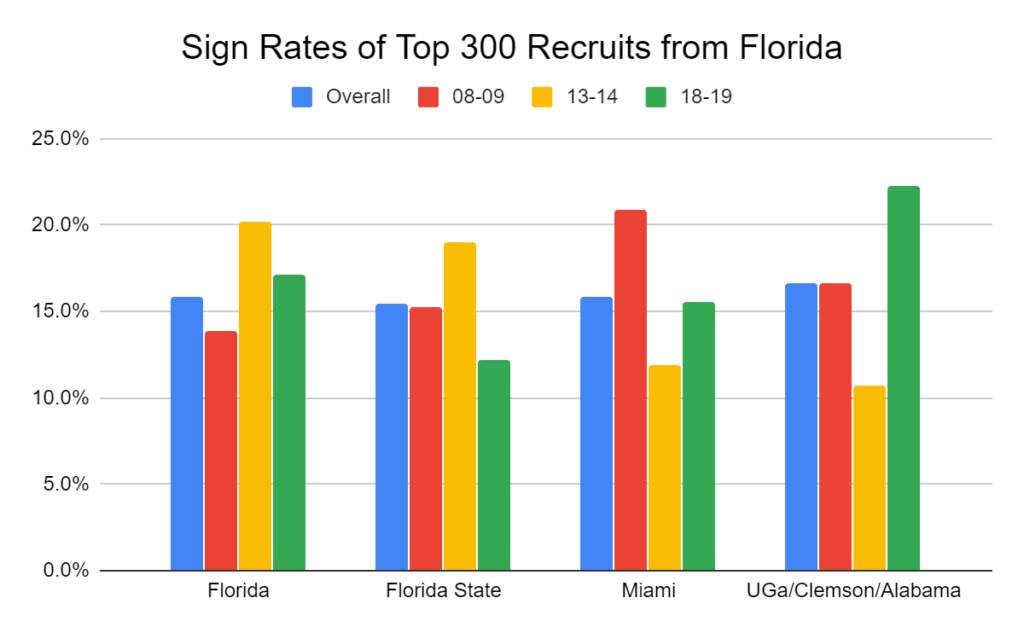

Florida, Florida State, and Miami will always be directly competing against each other for the Sunshine State’s best players. The real worry has come in recent years as out-of-state superpowers have encroached. When both Florida and FSU were fielding great teams in the mid-2010s, Georgia, Clemson, and Alabama, natural out-of-state geographic rivals for Florida recruits, didn’t fare well recruiting Florida. However, they combined to snare over 20% of Florida’s Top 300s in 2018 and 2019. Out-of-state schools secured Florida’s top nine recruits during these two years. Florida schools probably won’t benefit too much from a COVID-induced shift in recruiting preferences as their aforementioned rivals aren’t extremely far away for families of recruits.

Florida, Florida State, and Miami will always be directly competing against each other for the Sunshine State’s best players. The real worry has come in recent years as out-of-state superpowers have encroached. When both Florida and FSU were fielding great teams in the mid-2010s, Georgia, Clemson, and Alabama, natural out-of-state geographic rivals for Florida recruits, didn’t fare well recruiting Florida. However, they combined to snare over 20% of Florida’s Top 300s in 2018 and 2019. Out-of-state schools secured Florida’s top nine recruits during these two years. Florida schools probably won’t benefit too much from a COVID-induced shift in recruiting preferences as their aforementioned rivals aren’t extremely far away for families of recruits.

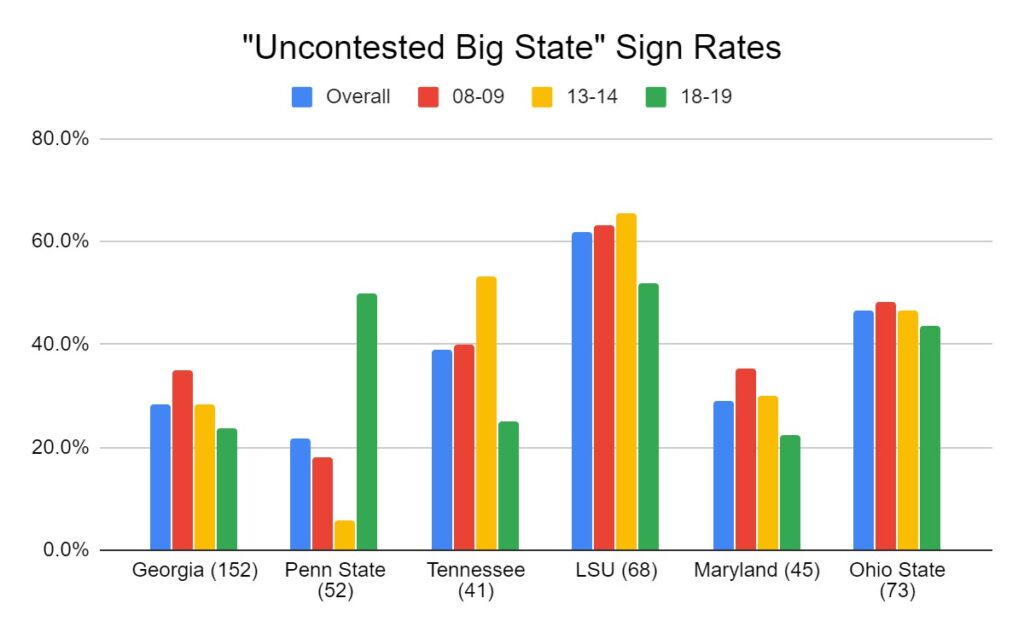

From the Big 3, it’s worth transitioning to what I’ll deem “uncontested big states,” states which produce seven-plus Top 300 recruits every year and have only one relevant Power 5 school. Tennessee (Vanderbilt), Penn State (Pitt), and Georgia (Georgia Tech) are all included here because the other Power 5 school in their state doesn’t pose much of a threat to them on the recruiting trail. Schools in this category can lay the foundation for a very competitive roster simply by convincing a chunk of the in-state talent available to stay. The number in parentheses is the amount of in-state Top 300 recruits that have appeared across these six recruiting classes.

Georgia

I wouldn’t have a problem if you called Georgia one of the easiest recruiting jobs in the country. Yes, it’s in a vulnerable geographic position, as the likes of Clemson, Alabama, and the Florida schools all have easy access to the Bulldogs’ home state. But the sheer volume of talent the Peach State produces means UGA could theoretically only pull about 40% of the whopping 25.3 average Top 300s in-state and still land a top five-ish recruiting class without even having to look too hard out-of-state. They don’t merely focus in-state, of course, and have stepped into Florida to pull four five-star recruits in the six recruiting classes. Kirby Smart has a national recruiting juggernaut operating out of Athens currently, and they’re poised to maintain that status into the future.

Pennsylvania

Penn State’s in-state recruiting results in the data set are incredibly disappointing, but that has to do with the instability associated with the acrimonious end of the Joe Paterno era more than anything. James Franklin has the Nittany Lions firing on all cylinders on the recruiting trail of late, as they pulled six of the 12 Top 300s in Pennsylvania in 2018 and 2019 while grabbing recruits across the fertile mid-Atlantic region of New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia. Rival Pitt pulled eleven of Pennsylvania’s 52 recruits across the data set, but eight of those signings came in 2008 and 2009. The Panthers aren’t terrible, but there’s been no juice around the program recently with Pat Narduzzi at the helm.

Tennessee

Tennessee is a very poor man’s Georgia: there’s one brand name school in the state, a largely irrelevant rival, and it’s susceptible to poaching – from the Big Ten schools to the north and bigger SEC names to the south. Problem is, the state doesn’t produce as much talent as you might think – there’s only about one Top 300 player from Tennessee for every four that come out of Georgia. The Volunteers’ recruiting has been decent in-state, though anyone deeming them a “sleeping giant” along the lines of a Texas or Miami is probably misguided. Soon-to-be third-year HC Jeremy Pruitt has been killing it with the 2021s with a class that ranks fifth nationally despite having only three in-state recruits. Still, it’s hard to foresee UT make a jump like Georgia did a few years ago into perennial national contention simply because of their smaller recruiting base.

Louisiana

LSU is an easy sell for in-state recruits because of the school’s name recognition, and there’s some insulation, as Louisiana recruits are facing a seven-plus hour drive to the sport’s out-of-state titans save Alabama. LSU has always prioritized in-state talents, and it shows, as LSU has the highest overall hit rate on in-state Top 300s of any school. It’s an enviable job, one that should never yield recruiting classes outside of the national top ten, now or in the future.

Maryland

Following LSU is the team I think that has done the worst with the hand it’s been dealt, the Maryland Terrapins. The 45 Top 300s deemed in-state includes recruits from DC, which is a metro ride away from the Terps’ campus in College Park. Maryland is located on insulated recruiting turf, as among Power 5 giants, only Penn State is located within seven hours. Still, UMD has never been able to bat over .400 with their in-state talent, which I attribute to the school’s TV-revenue driven move to the Big Ten and lack of a charismatic head coach in the past. Second-year HC Mike Locksley could change that, but it’s tough to fathom how keeping DMV recruits around became such an uphill battle for Maryland.

Ohio

Ohio State is in a very similar situation to LSU as the only Power 5 school in a mid-sized state, but the program has done a remarkable job fending off the likes of Penn State, the Michigan schools, and Notre Dame for in-state prospects while still primarily focusing nationally. OSU’s head coaching hire post-Jim Tressel was a big sink-or-swim moment for the Buckeyes, but they nailed it tabbing Urban Meyer and that success has only continued with former offensive coordinator Ryan Day in charge. The team is in the process of compiling a historic class in 2021 that features six in-state commits out of 19. Ohio State is not a difficult job to recruit well at, but Meyer and Day have made the most of that endowment and then some.

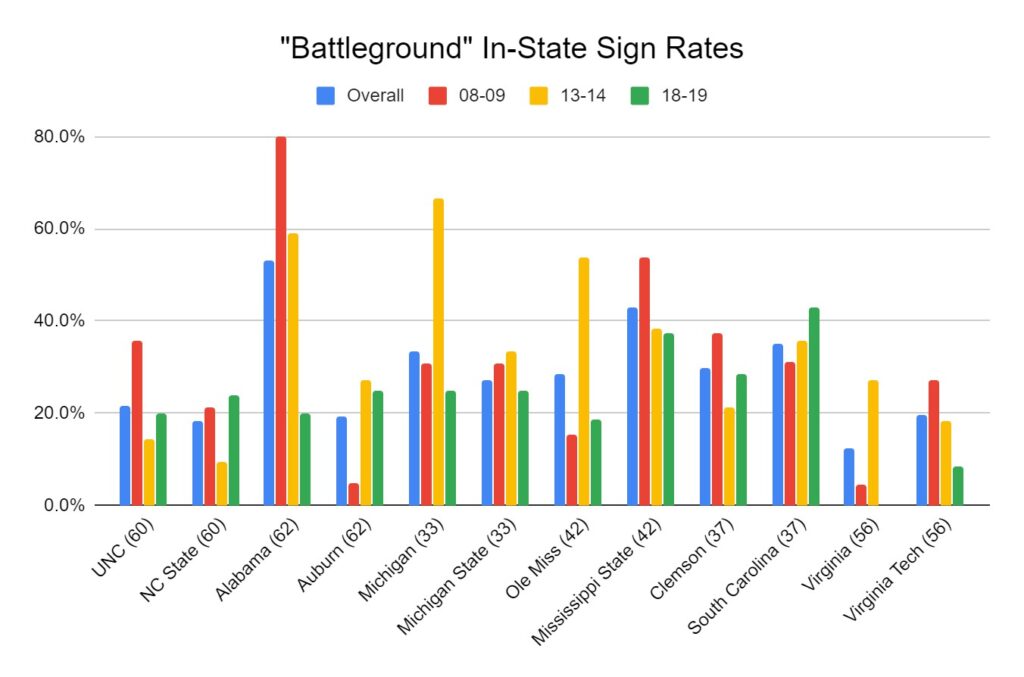

Next, we’ll look at “battleground” states which produce between five to ten Top 300 recruits per year on average but are also home to multiple relevant Power 5 schools, thus making competition fierce. These schools generally have a harder time recruiting in-state, having to fend off big out-of-state names and in-state rivals for a limited number of top recruits.

North Carolina

There are four Power 5 schools in North Carolina, and UNC and NC State have done a good job of crowding out Duke and Wake Forest. The two schools’ recruiting results in a fairly fertile state have been middling, and their on-field results have similarly been up-and-down. Clemson and Tennessee have done well in North Carolina recently, but second-year Tar Heels head coach Mack Brown has taken the nation by storm with his recruiting efforts recently, which began when Brown delegated a UNC assistant to visit every high school in the state. North Carolina has the ninth-best class in 2021 currently, with a whopping 14 of their 17 commits being in-state kids.

Alabama

As mentioned, Alabama has shifted its priorities from dominating in-state first and foremost to a more nationwide strategy in the last twelve years, with obviously spectacular results. Despite this, for a team that would like to consider itself a top-ten or fifteen program, archrival Auburn’s in-state results have been poor. The Tigers have solid pipelines in Georgia and Florida, so if they can maintain those while picking it up in-state, they could put together some really formidable classes. As 2008-09 showed, though, if in-state kids are getting pursued hard by Alabama, they’ll likely wind up there.

Michigan

As far as misaligned fan expectations go, the coaches at Michigan and Michigan State have it rough. If Michigan is to return to its former glories, or Michigan State to its recent heights under Mark Dantonio, they’ll need to find sources of talent outside of the Great Lake State, which produces only about five Top 300 recruits per year on average. The volume of talent in Michigan and neighboring states certainly isn’t enough to see both schools succeed simultaneously, and the likes of Ohio State and Wisconsin are probably more attractive options for those players anyways. And anyways, both UM and MSU’s in-state recruiting results haven’t been all that impressive in the first place. It’s tough to imagine either team in the top ten consistently in the 2020s unless both their in-state rival and Ohio State experience a dropoff.

Mississippi

A similar situation to Michigan’s, though both Ole Miss and particularly Mississippi State have done a solid job keeping in-state talent. Again, there’s probably no room for both schools to be posting 8-9 win seasons at the same time, and you know any top-50-type player from Mississippi will have the likes of Alabama and LSU all over them. MSU topped out in the 9-10 win range under Dan Mullen during the 2010s, and it’s tough to imagine a team from the state surpassing that.

South Carolina

South Carolina has clearly prioritized the in-state recruits their much more successful rivals Clemson haven’t, because the Gamecocks have actually gotten the better of the Tigers when it comes to recruiting the Palmetto State. Like with Alabama, if Dabo Swinney with his Midas touch feels that in-state recruits will be an easier sell with COVID, they’ll likely start committing to Clemson in waves. With Clemson in-state, Georgia to the west, and North Carolina’s hot streak directly to the north, it will be quite difficult for South Carolina to see a large uptick in their on-field results in the near future considering the state doesn’t produce a huge volume of Top 300s to begin with (6.2 on average).

Virginia

Virginia usually produces a decent amount of talent, but out-of-state schools certainly aren’t afraid of raiding it – highly-ranked talents from the data set including quarterbacks Christian Hackenberg, EJ Manuel, Mike Glennon, and Tajh Boyd all left the state for college. In-state Power 5s Virginia and Virginia Tech are barely holding their own defending their home state, pulling seven and eleven Top 300s out of 56, respectively. These are two schools that could fare better recruiting after COVID, as UVA is coming off of a nine-win season and most of the ACC and Big Ten schools that have been dominating the state’s recruiting are a six-plus hour drive for recruits.

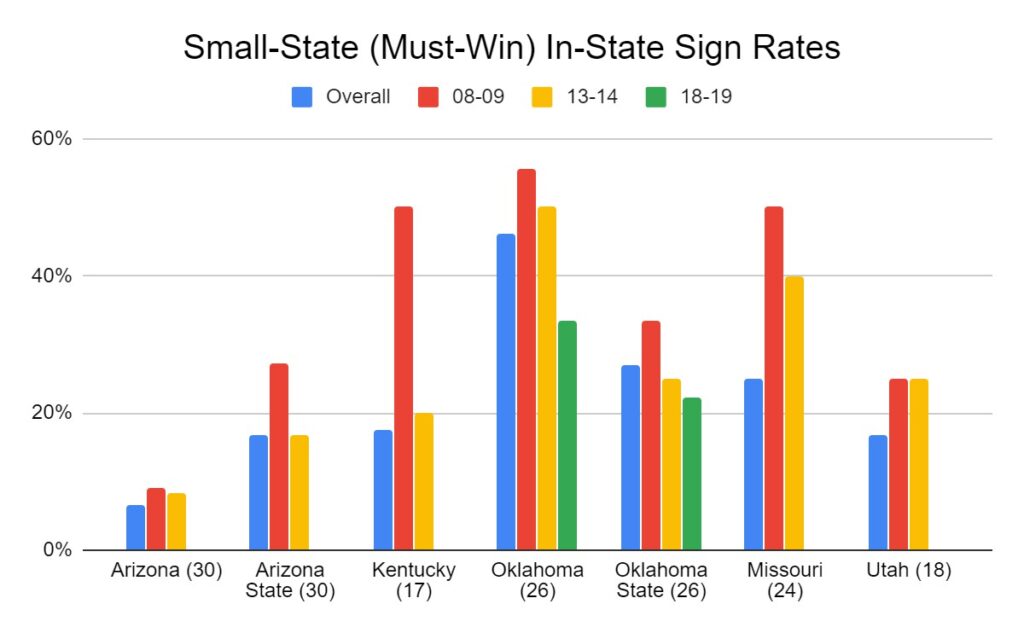

Finally, we’ll turn to some lower-volume states with notable Power 5 programs. I’ve deemed in-state being a “must-win” for their success post-pandemic.

Arizona

Another tough state to recruit, as it gets hit hard by Californian neighbors up north and Big 12 schools like Texas and Oklahoma from the east. Seeing Arizona produce only 30 Top 300s across the six classes was surprising and may not be the norm for long, as the state has seen population growth and churned out nine Top 300s in 2021. Kevin Sumlin has a particularly tough job at the University of Arizona, which is playing second-fiddle on some already lower-volume turf, but it’s not like he’s been doing more with less, either. Herm Edwards at Arizona State has created some buzz around the program recently, and it would make sense to forecast better on-field results in the future considering UA’s irrelevance and the solid recruiting classes Edwards could compile if he solely focused on a growing Arizona and an always-stocked California with USC and UCLA’s programs down for now.

Kentucky

Undoubtedly a hard sell as they occupy a lower-volume state with rivals Louisville, the Wildcats have been strong on the recruiting trail recently with a strategy that has prioritized the Ohio recruits that Ohio State chooses to pass over. Their in-state results have been poor, but that is obviously a function of UK’s general struggles in the 2010s more than anything. Mark Stoops’ teams have won a combined eighteen games in the last two seasons, however, and Stoops looks to be on the verge of building something sustainable in Lexington.

Oklahoma

The University of Oklahoma’s in-state sign rate has fallen precipitously over the last decade, a similar trend to what we saw with Alabama. The Sooners have been killing it with footholds in Texas and on the west coast, but what’s surprising is Oklahoma State hasn’t taken advantage of the small opportunity in the Sooner State their Bedlam rivals have left them. Mike Gundy’s program has also seen its in-state sign rate fall slightly, which is a bit quizzical. Gundy has done more with less for a while now, but the Cowboys occupy an undesirable spot in the national recruiting landscape, pandemic or not.

Missouri

It’s easy to forget Gary Pinkel won ten games at Missouri five times between 2007 and 2014 because the Tigers have been so forgettable since his departure. They snared at least 40% of Missouri’s limited number of Top 300s in the data set years with Pinkel, and then went a combined 0 for 11 with those players under Barry Odom in 2018 and 2019. As the only Power 5 team in the state, the Tigers need to be able to control Missouri, particularly the St. Louis area, to even have a hope of returning to consistent .500 football in the SEC. New coach Eli Drinkwitz has made that a priority, with six Missourian recruits among a 2021 class that currently ranks 25th in the country.

Utah

The University of Utah Utes’ relative struggles in-state are one of my more surprising findings. An incredible stat: every recruiting class in this data set (there were some mediocre years in between) was being courted during a season in which Utah won at least nine games. The state has produced 18 Top 300s during those years – only 3 signed with Utah. With 3 going to BYU perhaps as a function of a LDS church connection, that still leaves twelve recruits that ditched the state. It’s not as though poachers have easy geographic connections either – the Utes’ closest dangerous threats, Oregon and USC, are quite a ways away. But recruits have spurned Utah for the likes of Alabama, LSU, Michigan, and Washington. Head coach Kyle Whittingham has still made it work, of course.

Wrapping up, examining long-term program trajectories in college football, it’s always important to keep in mind that some schools have it much, much easier than others. Geography is the most predictive factor in determining long-term success, and it all depends on how many recruits are nearby and how many Power 5 rivals are nearby. Schools like Clemson and even Oklahoma State are the outliers and have benefited from great program stability. Overall, though, for all of college coaches’ riffs on “culture” and whatnot, winning college football games remains largely predetermined.