This piece appears as part of Carrying On, an ongoing column written by members of the Voice masthead.

Around junior high, I began to play an exhausting game of hide-and-seek. It started with figuring out how to style my dress code-approved polos underneath cardigans and sweatshirts so my classmates wouldn’t see that they were from Walmart or Target and were not the form-fitting Aeropostale shirts that were so trendy at the time. It evolved to insisting on being dropped off near the band hall in the back of the school, where fewer people would see my parents’ broken-down car. I learned to tell my teachers I’d forgotten my field trip money rather than explain that my parents needed a few extra days to get the cash together. In this game of hide-and-seek, instead of waiting for someone to count to ten and call “ready or not!”, I was hiding my family’s financial situation from everyone I knew.

I got better at the hide-and-seek once I started high school and got my first job. I never wanted anyone to think that I was rich; just average was good enough—not wealthy enough to be snooty, but not poor enough to be trashy. I was white and made good grades—exactly the kind of person my small town expected to be a nice, middle-class American girl. When I was accepted to Georgetown, everyone congratulated me on receiving a scholarship. I didn’t correct them when they assumed that my need-based financial aid was a merit award. I looked forward to starting college, where everyone would live in the same shitty dorms and eat the same bad food, and where, finally, off-brand clothes and chipped paint jobs wouldn’t betray me.

For five semesters, I used my hide-and-seek strategy to my advantage, thinking I could successfully hide my income status even as I was surrounded by the wealthiest population I’d ever encountered in my life. Though I never totally felt like I belonged among the students who wore Golden Goose sneakers to class, I found a group of friends in similar situations to mine and staff members I knew I could count on for support. But this year’s coronavirus crisis threw back the curtains, and I realized that the game I’d played all this time hadn’t made the differences between me and my classmates disappear. With nowhere left to hide, I had to reckon with the realities of being a low-income student at an elite university.

According to the New York Times, 21 percent of Georgetown students are in the top 1 percent, and the median family income at Georgetown is $229,100 per year, the highest among its peers in the Big East. In my hometown, the median family income is $58,502 per year. Even there, I nearly always found myself at the bottom of the wealth pyramid among my friends. Public schooling pioneer Horace Mann was wrong when he called education the “great equalizer of the conditions of man.” Now entering my senior year at Georgetown, I am no closer to being in an even comparable financial position to my peers. Under our current economic system, there is no equalizing the top 10 percent in America and the bottom 20 percent. The widespread economic breakdown caused by coronavirus has only made this more obvious.

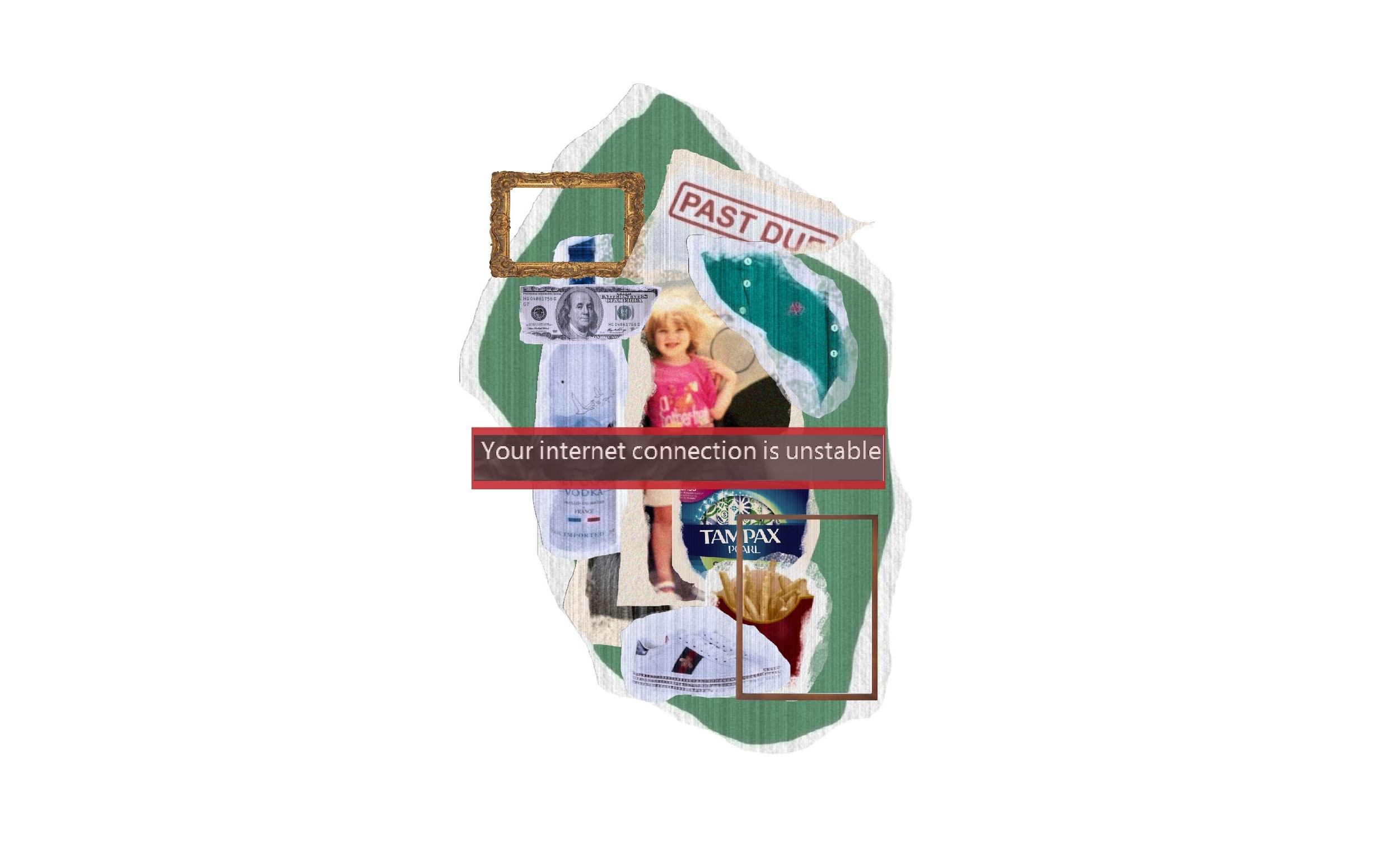

When COVID-19 shut down the country, my father—our primary breadwinner—had already been out of work for months after being laid off on my 21st birthday in December. After the preschool my mom worked at shut down, my family was being solely supported by her second part time job, where she made $15 an hour—less than what I made at my work-study position on campus. At the same time, I moved back home into a three-bedroom house I shared with six family members. I didn’t have a bed, so my parents set up a folding cot from Big Lots in the room I shared with my two sisters.

When I logged onto my first Zoom class and our professor had each class member check in and update the rest on how they were doing, the differences between me and my peers became uncomfortably evident. Multiple classmates described hunkering down at their second homes to wait out the pandemic. Another casually pointed out her father’s prestigious award on the shelf behind her. I tried to keep up with everyone else’s spiel, but it didn’t really matter. My WiFi was struggling to maintain a connection, and the call kept cutting out.

Those first few weeks of virtual classes made it even more apparent how ludicrous the game I’d been playing was. While I’d been worried about affording a flight home to Texas, my classmates had been petitioning for grading policy changes and tuition reimbursement. Both of these dramatically affect student life, but were nowhere near as important to me as the immediate panic of finding myself stranded during a pandemic with no place to live and no way home. When you’re poor, surviving the next two days or two weeks feels much more vital than the big picture of GPA or tuition payments.

I don’t blame my peers for having different priorities than I do. It’s all part of coming from extremely different backgrounds and learning in an environment that has done little to close the gap. Despite need-blind admissions and a promise to meet every student’s financial need, being a low-income student at Georgetown still feels like being a zebra in a field of Kentucky Derby champions. Everything about the school—from the million-dollar houses outside the front gates to the obsessive club culture that favors students who don’t need to work 30 hours a week—is designed around the wealthiest among us rather than the poorest. The stallions are always going to end up winning a race built for them.

It would be a mistake to assume that COVID-19 has created these gaps in educational access. All it’s done is bring them to light. I’ve watched for three years as classmates blew their money on expensive parties and high-class restaurants, or told me that they chose not to work to focus on school as I skipped social events to make it to my job. I’ve missed readings because I couldn’t afford expensive textbooks, and, on more than one occasion, I’ve relied on the Women’s Center because I couldn’t afford tampons. I’ve learned to avoid visiting the Hoya Hub when my colleagues at the Voice might be in our office down the hall, so no one would know that their editor-in-chief didn’t have grocery money. All the club dues or the Venmo requests for an Uber because the bus would take too long add up. For most of my education, I’ve pretended the massive wealth inequality at Georgetown didn’t bother me, hiding the fact that I’m a low-income student as if it were shameful or dirty. It’s time to stop pretending that there’s something wrong with me or my family and recognize that it’s the system we live in that’s flawed.

I am extraordinarily grateful to Georgetown for giving me the financial aid to receive a world-class education I could never have afforded on my own. But when Georgetown announced a 10 percent tuition decrease in July, I knew it wasn’t meant to help students like me. When I graduate this spring, I won’t have paid anywhere near 10 percent of one semester of tuition in my four years combined. The tuition cut was a move calculated to appeal to the wealthy students who could afford to attend Georgetown regardless of the price tag for one semester, in stride with a university model that has always catered to those whose parents shell out the most money.

I was wrong to think that walking through Georgetown’s front gates would make the social inequality I’ve felt all my life disappear. If anything, it seems to have been exacerbated. But I hope that one day, when I send my children to school, no one will feel like they have to play hide-and-seek. In that version of collegiate America, quality higher education will be a reality for every student who wants to pursue it.