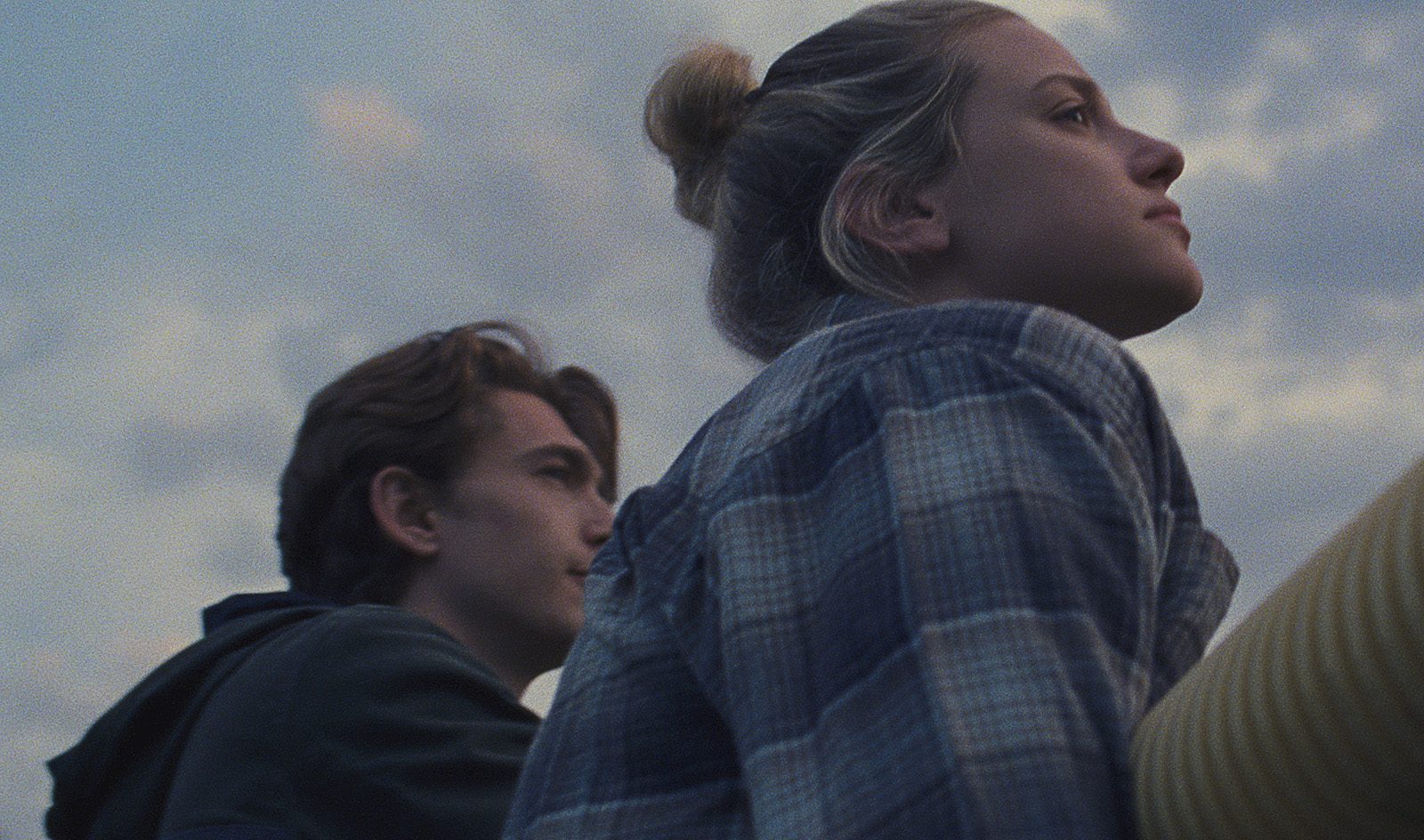

Chemical Hearts (2020) may be a romance, but it was never supposed to be a love story. Based on Kyrstal Sutherland’s novel Our Chemical Hearts, the film follows the doomed relationship of teenagers Henry (Austin Abrams) and Grace (Lili Reinhart) as they navigate their final year of high school. While the film aims to be an emotional exploration of what it means to be a teenager, the key topic of mental health is severely mishandled with unequal character development and reductive, tactless metaphors.

Henry and Grace meet in their senior year when they are asked to share the position of editor in chief for the high school newspaper. From the beginning, it is obvious that Grace and Henry lead very different lives: Grace is quirky and mysterious, but haunted by grief, while Henry lives what resembles a perfect life. Because of that perfection, however, he feels like his high school life has lacked any interesting events or revelations—at least, until Grace enters his thoughts.

The film’s biggest flaw is the inequality between Henry and Grace’s stories. Grace’s character is fascinating, and her experiences with the altering effects of grief, trauma, depression, and survivor’s guilt are some of the most important topics in the movie. From Henry’s point of view, however the viewer doesn’t get to engage with those themes beyond how Henry perceives them.

Reinhart, in an interview with the Voice and other publications, spoke about why she found Grace’s character so compelling. “I loved Grace’s darkness and vulnerability,” she said. “I hadn’t yet been able to play a character who felt so raw and not put together.”

Grace’s experience with mental illness could have added so much to the movie had it been properly addressed. However, by only exploring Henry’s feelings about Grace’s mental health, the film pushes its most interesting elements to the sidelines and supplants them with extremely problematic perspectives on grief, depression, and recovery.

At one point in the film, Henry basically stalks Grace, trying to make sense of her mystique. That pursuit leads him to a graveyard where, unbeknownst to Grace, he watches her break down over the gravestone of her late boyfriend, killed in a car accident. Later in the film, Henry again witnesses Grace break down while trying to run with an injured knee. This behavior is uncomfortable and certainly not appropriate, yet Henry faces no consequences for stalking the girl that he has suddenly fallen in love with. He learns about her past trauma without her permission, or even her knowledge. This imbalance of information sours future moments between the couple, such as Grace revealing her past to Henry, because he already knows what she is telling him. It feels like broken trust and an invasion of privacy.

Henry’s behavior is the reason that their relationship was doomed from the start. His idealized version of Grace leads him to want more from her than she can give, and his constant efforts to “fix” her pushes her too close to the edge. He claims to love her as she is, yet the second she makes a single step forward in her recovery, he expects that to be forever, seemingly viewing recovery as a quick linear progression. Henry acts as if Grace owes him her undying love because she returned some of his affection. This entitlement is so pervasive that he finds it ridiculous that she hasn’t gotten over her late boyfriend yet. When they break up, everyone focuses on consoling him, and there is no exploration of how he contributed to the relationship’s decline.

The breakup itself is a scene worth calling attention to. This emotional climax serves both as the confession of love and the end of the relationship. After Henry finds out that Grace lives with her late boyfriend’s family, he accuses her of being unable to let go of the past. This scene is both heartbreaking and enraging, as it becomes startlingly clear to the audience that Grace and Henry are not compatible. Grace is not ready for a new relationship, and Henry acts far too entitled to her love, often minimalizing her grief. Though the flaws are there for the audience to witness, they aren’t given the same attention as Grace’s declining mental health.

The consequences of portraying Henry as an innocent boy who had his heart broken by the “manic pixie dream girl” is that the blame then falls entirely on Grace and her mental illness. What is clearly a toxic relationship between two incompatible people becomes framed as a story of how the girl with depression could not love Henry back. After one last emotional climax between the two where Henry “selflessly” helps the girl who broke his heart let go of her late boyfriend, Grace takes time off of school to focus on her mental health. Without any insight into Grace’s internal struggle with depression and grief, it seems like Henry’s intervention was the sole reason she started going to therapy. Though their relationship may have been the catalyst for Grace realizing that she needed help to move on, the pacing casts Henry as a savior who fixed the broken girl.

Director Richard Tanne describes Chemical Hearts as a doomed love story: “I think what I ultimately take away from it is that not every romance is supposed to be a love story,” he said. “I think of this as a failed love story. It’s a failure because it’s two people who want each other for the wrong reasons.”

This is a perfect description of what the movie aims to be. However, this failure of a relationship overshadows the significantly more important discussion about mental health so thoroughly that it becomes a plot device to place all the blame on.

Chemical Hearts had the potential to explore a lot of important topics related to teenage mental health. The actors do an excellent job of bringing raw emotion into the movie. However, the story wrongly brushed off Henry’s morally questionable actions and never gave adequate attention to understanding Grace’s perspective. In attempting to subvert the cliche of a campy teenage movie, Chemical Hearts dangerously mishandles grief and depression, completely undermining its own themes and goals.