Content warning: This article references eating disorders and body image.

I keep forgetting I have an eating disorder (ED).

It almost seems impossible, really, that most of the time I forget about this thing that has sat heavy in my chest for 17 years. There’s no other aspect of my life that is simultaneously so crucial to my internal narrative, and yet so distanced from it. Most days, it feels like my ED belongs to someone else—or millions of someone else’s—more than it does to me.

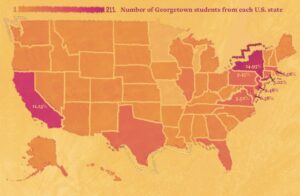

It is strangely minimizing to know that about 10 percent of the U.S. population will share my experience sometime in their life. What seems so personal to me, so hyper-individualized when my refusal to eat staves off sleep and causes my stomach to growl at 2 a.m., is in reality more common than being from my home state. It is more common than for someone to live in D.C., or identify as lesbian in the U.S., or watch my favorite TV show—all things I would not have said are personal to me. It does not help that I—a young woman who became aware of her ED in high school and is still struggling with it into adulthood—fit right into what could be considered the “face” of an ED.

There are certain stereotypes of people who have EDs: damaged maternal relationships, throwing up in the high school bathroom stall, using caffeine or nicotine as appetite suppressants. When I go down the list, all I see are checkmarks. All the trauma I call mine has been heard before, be it through the mouths of poets, or young girls on TV, or ED awareness posts. Sure, I could talk about my mother passing on her ED as an inheritance; I could talk about her hiding food from me; I could talk about hiding food from myself. I could talk about eating three meals in the span of three hours and then throwing it all up. I could insist that my suffering is not beautiful and I could remind you EDs are not just for girls with bare bones. I could list every single time I had a panic attack in a dressing room or at a restaurant or after eating one more bite than I promised myself. I could explain how every time I try to get just a little control, I seem to lose it all again. And what you would hear is exactly what is expected: I am the cautionary poster child, the concerning childhood best friend in the movie. I am thousands of them, all at once.

To be fair, being this face of my disorder provides a degree of privilege. If I seek treatment, I will be believed in a way many men and BIPOC would not be; doctors will not question the young white woman with the fluctuating weight. Still, I feel my own face merging with the millions of young women with stories just like mine, and I cannot help but feel lost. I have never wanted my ED to be my personality; in fact, I talk about it rarely as to limit its power. But I also cannot pretend it is not something that has affected me—not just other survivors.

For so much of my life, I longed to be understood. As any angsty middle schooler with multiple undiagnosed mental illnesses would, I made it a habit to come home and lay under my too-pink quilts, crying about how I was alone—how there was no way that my suffering could be communicated to those living outside my head. I could have never conceptualized then that I would one day meet so many people whose experiences aligned with mine that I would feel like I could no longer call my experience my own.

Indeed, eight years later, my life is littered with reminders that my suffering is shared. Conversations with friends, social media posts, and representation in the media are all there to make sure I don’t forget, even for one day, that I can’t claim EDs all for myself. I don’t resent those reminders; I want others to feel comfortable sharing their experiences. I’m glad popular media is raising awareness about EDs, and I know the infamous Instagram resource cards could be saving lives. But each time I see one, I feel like I am doing so from the outside—like I do not have equal claim to that narrative. And I feel the gulf between me and my experience grow.

I can’t say exactly how or when I separated myself from my ED so entirely. Partially, I think it’s because I have never truly told the story of my ED—not publicly, and not all to one person. Even the narrative in my own head is often broken up into segments. There are months I remember struggling. There are strategies to cope crystallizing. There are rediscovered early memories that led to disordered eating habits. Each version of me with an ED feels temporal, fleeting. In the absence of that story, I fill in the gaps with a generalized, sanitized experience pulled from the rest of the world.

This sanitization is not helped by the fact that many people in my life also struggle with disordered eating. I have adapted to being their confidant and advisor, always expected to reply with sound, objective advice. At some point, I decided I could not be the strong friend while also being the friend who couldn’t eat right herself. Being strong required less explanation. So, I told myself I was not part of the group of people who really suffered from disordered eating. I wasn’t going to end up in the hospital. I didn’t need to be worried.

I don’t want to be my ED. But when I forget I have my ED, when I let my story be subsumed by those I see, I also forget to take care of myself like I have an ED. I forget that what is a forgetful day for some people can be a trigger for me—that I cannot engage in conversations about eating habits with people who can’t list everything they’ve eaten in the last two days. Just because my internal self has abstracted herself out of the community of people with EDs does not mean the very real version no longer has one.

Any of us who experience genuine empathy and understanding around our trauma should be grateful for it. We should tuck it in our pocket and remember that when we feel crying-at-3 a.m. desperately alone, we aren’t. But just because we are not alone does not mean we are not individually suffering, and we can’t forget that.

I know my journey is important to me. I know it contains the moments I have hated and loved myself most, the strongest I have ever been and the weakest I have ever felt. I know that someday, if I ever want to honestly tell myself I am getting better, I will need to be able to lay out that journey, a morbid storyboard of hurt.

The first several times I tried to write about my ED, I approached it as a generic member of a community. While this is technically true, I was just doing the same thing I always had, negating and devaluing my individual experiences. It wasn’t until I became so emotionally exhausted from trying to write around my own ED, trying not to claim this story as my own, that I knew I had no other choice.

Abstracting ourselves out of our own narrative only leads to powerlessness. When we take ourselves out of the picture, we also remove all agency, all hope to improve. Even as I find solidarity in a more transparent and tolerant world, I cannot let myself forget that there is still something inherently personal about my ED—after all, I call it mine.