Part-time faculty at Georgetown, called “adjunct” or “contingent,” have an outsize role in supporting the university’s student body. They are responsible for core classes, career advice, letters of recommendation, and much more. At the same time, they receive insufficient compensation and lack the same benefits available to their full-time tenured and tenure-track colleagues. Students are not immune to the disparity either; many advocates point out that the working conditions for professors become the learning environment for students themselves.

As contingent professors make up an increasing share of faculty at universities across the country, disparities between their job description and de facto duties continue to grow. While some, including those at Georgetown, have union representation, many do not and have few avenues for collective bargaining, leading to gaps in pay, access to benefits, and career advancement. The glut of highly educated and qualified graduates vying for the same few positions and the lack of professional mobility for contingent appointments creates a class of professors who feel exploited and disconnected from the communities they serve. Since the early 2000s, the movement toward equity for faculty on contingent appointments has expanded to a national scale and begun to create the first waves of change.

At their best, contingent positions let universities benefit from the experience and expertise of professors who can only devote time to one or two courses. They allow schools like Georgetown to extend fellowships and short-term appointments to government officials and career professionals who give students insight into the “real world.” Professors on contingent appointments have the latitude to pursue other projects: running businesses, teaching elsewhere, or lightening their workload after a full career. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t professors. (https://fernandez-vega.com)

“They are not just invested in careers and financial compensation but are largely here because they care about the students and want to see them succeed,” Prof. Christopher Shinn, who has held a contingent appointment at Georgetown since 2008 and a more recent tenured position at Howard University, said of his part-time colleagues. “They want to feel that they’re an integral part of university life.”

The idealized contingent model no longer reflects reality. Nearly two-thirds of all university faculty are contingent, including many for whom teaching is their primary career. The Georgetown main campus itself employs about 1,000 faculty on contingent appointments. That means core classes—and the majority of daily teaching responsibilities—fall on faculty who are not afforded the same benefits, job security, or voice in department governance as their full-time tenured and tenure-track counterparts.

“This is not a Georgetown problem; this is a university problem,” Prof. Sara Collina, who teaches part-time in Georgetown’s Women’s and Gender Studies program, said. Collina owns and operates a small business and is also involved in advocacy, but for some faculty, contingent positions are their only source of income.

New contingent faculty receive a minimum of just $7,000 for teaching a semester-long, three-credit course and teach an average of 1.4 courses per year since they are limited to a set number of hours. As of the latest round of collective bargaining between Georgetown and the Service Employees International Union Local 500 (SEIU), which represents adjunct faculty at Georgetown and nine other universities in the DMV area, course rates increased by $200 or $250 above the $7000 base rate for the fall 2021 semester, depending on how long a contingent faculty member has taught at the university.

Pay isn’t the only disparity; faculty on course-by-course appointments do not have access to the healthcare benefits that full-time employees do, and their employment status is unassured.

Prof. Mary Jane Barnett described the uncertainty of a contingent position, even after teaching as an adjunct at Georgetown for more than 25 years. “If you’re an adjunct there’s always the thought in the back of your mind: What about next semester?” she said.

To compensate, many professors pick up additional contingent appointments. Prof. Rebecca Boylan, who has taught at Georgetown since 2006, now holds a full-time position at Howard

University as well. “I think universities should consider more justice in how they are responding to their faculty,” she said. “There’s a lot of service I’ve given to Georgetown for a long time.”

On top of instruction, contingent faculty serve the university by providing independent scholarship, writing letters of recommendation for students, and, most recently, developing virtual learning strategies. None of these services, which go above and beyond contingent faculty’s restricted job description at the university, are compensated. Fees are calculated only with respect to hours in the classroom (or on Zoom).

That attitude toward compensation and labor is at odds with the stated values of educational institutions like Georgetown, where learning is a core value in areas beyond the classroom. “I don’t ever expect businesses to have empathy for workers. And I think the university sees itself as a business,” a faculty member in the College, who wished to remain anonymous, said.

“But I would hope that it sees itself as more than that, and I certainly don’t see my students as customers at all.”

The university, meanwhile, insists that its goals align with those of contingent faculty. “We deeply appreciate all that our adjuncts do to support our university community. They are key contributors to the formation of our students,” a university spokesperson wrote in an email to the Voice. “We are committed to working together to honor what each individual brings to his or her work and to the fabric of our university community.”

Maria Maisto (SFS ’89, MA ’92), a leader in the movement for more equitable compensation for contingent faculty, blamed a broader shift in higher education toward a more profit-oriented model. “I would say [the contingent model] has been exploited for political and economic reasons—to serve the corporatization of higher education,” she said. Maisto is president of New Faculty Majority, an organization dedicated to improving equity for faculty in higher education.

“It’s an incredibly good deal to have so much of the teaching done by adjuncts,” Collina pointed out. The median salary for a tenure-track faculty member is roughly four times the equivalent of adjunct pay for the same course, making contingent staffing much more cost effective. But the arrangement leaves little room for trust. “I can’t count on Georgetown, and Georgetown can’t count on me. If there’s a commitment on both ends, you’ll invest in each other.”

For Collina and other contingent faculty, recognition as equal community stakeholders would go a long way toward improving morale. “What we have now is, we have this sort of sub-class of faculty, and of course they bear the largest amount of teaching at the university,” Shinn said. He believes more balanced consideration for the three main elements of a professor’s duties to teach, research, and serve would improve the disparity between faculty on different appointments.

These disparities reflect and perpetuate societal inequities. People from communities historically excluded from higher education increasingly struggle to find tenure-track positions and end up on contingent appointments instead. “It’s absolutely true to say that it’s gendered,” Maisto said. The increase in access to education and faculty opportunities for women, people of color, and people from working class backgrounds coincided with the widening gulf in employment structures. “That was when the shift began and the profession started to be devalued,” she said.

An Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System study on faculty demographics found the percentage of women faculty on the tenure track declined from 13 to 8 percent between 1993 and 2013. At the same time, the percentage of women in contingent positions increased by 8 percent. “Women are in the majority in the humanities and general education, where the lowest-paid positions are found, again teaching the core courses, often to the most vulnerable students,” Maisto said.

The narrative of discrimination in contingent work is borne out in the lived experiences of some Georgetown faculty. “I worked for a number of years, then I was married. I had two kids and took some time off to be with my daughters,” the anonymous faculty member said. She is fully qualified, with a Master’s degree and Ph.D.—an enormous investment to result in a contingent position. “I’ve picked up work on the side when I can just to make ends meet,” she added.

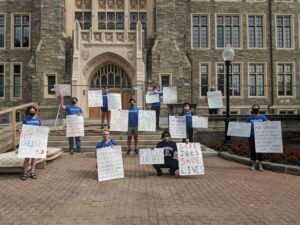

The present vulnerabilities were made especially visible over the past year and a half. In March 2020, Collina wrote a letter to President John DeGioia with the subject line: “Adjuncts are stepping up, please step up for us.” In it, she detailed ways that contingent faculty are shut out from community at Georgetown, especially at a time when community was all that bound the university together. “Faculty meetings? I’m not invited. Teaching awards? I’m not eligible. Grants? Not for me,” she wrote.

The advent of the pandemic, which coincided with Georgetown adjuncts’ latest round of union collective bargaining, exposed the position’s unique vulnerabilities.

When Georgetown moved all instruction online, contingent faculty—like all faculty and students—had to adapt to teaching virtually and redesign their courses. The university offered training courses to aid them, but Shinn said, “We’re not paid for taking this training and so on; we do it because it’s necessary to do our jobs.”

As recently as 20 years ago, contingent faculty had few means by which to advocate for just compensation. Since then, unionization and community pressure in higher education have forced gains, however modest, in critical areas: compensation, job security, professional advancement, and community involvement.

The latest contract includes annual pay increases through the fall 2023 semester, with more experienced faculty seeing the biggest raises—up to $7,750 for a three-credit course. It also guarantees adjuncts are notified of their employment status for the next academic year by June 30 at the latest.

Faculty also have a pathway to greater job security under the agreement. Adjuncts who have taught at least three courses for five of the past eight academic years will become eligible for regular full-year appointments with the option for renewal.

The current contract is in effect until 2024, after which the union may renegotiate.

The SEIU’s main goals are improving compensation and job security, according to Anne McLeer, SEIU Local 500’s director of higher education and strategic planning.

“We will continue to seek to push to the point where adjuncts have equity or parity with full-timers in terms of pay and also even in terms of benefits,” she said. “There’s still a long road to go.”

Unions have been essential for improving faculty working conditions. The organizations are important for faculty advances because contingent work is transitory by nature, which makes organizing efforts difficult to maintain. “Eventually, many of us will move on. It’s not sustainable,” Maisto said. Unions create longevity and infrastructure that address problems in mobilizing short-term employees for a long-term campaign.

Since she began her work in the movement more than a decade ago, Maisto believes unions and collective action have offered the greatest gains. “They’re effective in part because they provide an infrastructure and a culture and a community through which the faculty can be provided support and continuity of effort in negotiating improvements,” she added.

As with any movement, however, the chosen path forward does not help everyone equally, and the union representing Georgetown’s contingent faculty is not popular with all its constituents. “I would like to feel as though adjuncts and the union are working hand in hand, as one unit. But sadly, that’s not the case here,” the anonymous professor said. She pointed out that in addition to their public messaging, both the union and the university have separate agendas that can conflict with acting in the faculty’s best interests.

In the past, she explained, this has led to the university not approaching negotiations with an open mind. “I didn’t see any real seriousness of purpose, unfortunately, on the part of the university in terms of trying to be invested in and thinking about the needs of adjunct faculty,” she said.

Boylan also felt the union’s effect had been minimal. “From my experience, it didn’t change things at all until very recently,” she said.

Internal disagreements between the union and the professors it represents have the potential to slow further gains. “The union is as strong as its members. We want this union to get engaged in social justice issues that reflect our membership and the union,” McLeer said. Collective bargaining’s power comes from the size of the collective, and without widespread buy-in, the union’s efforts to secure gains for all contingent faculty could suffer. Despite this, faculty with concerns about the union’s agenda, the university’s response, or slow progress may not join its membership.

Some faculty, including Collina, see better opportunities for progress through alternative mechanisms. “Frankly, our leverage is the students,” she said. Students are the most likely to experience the direct impacts in the classroom of what happens when a university undervalues its contingent faculty, who deliver most of the instruction.

Collina argues students’ power stems from their role as vocal and foundational members of the university community. “Georgetown needs you and your classmates to love Georgetown and to respect it and honor it and believe that this is a community you can be proud of,” she said.