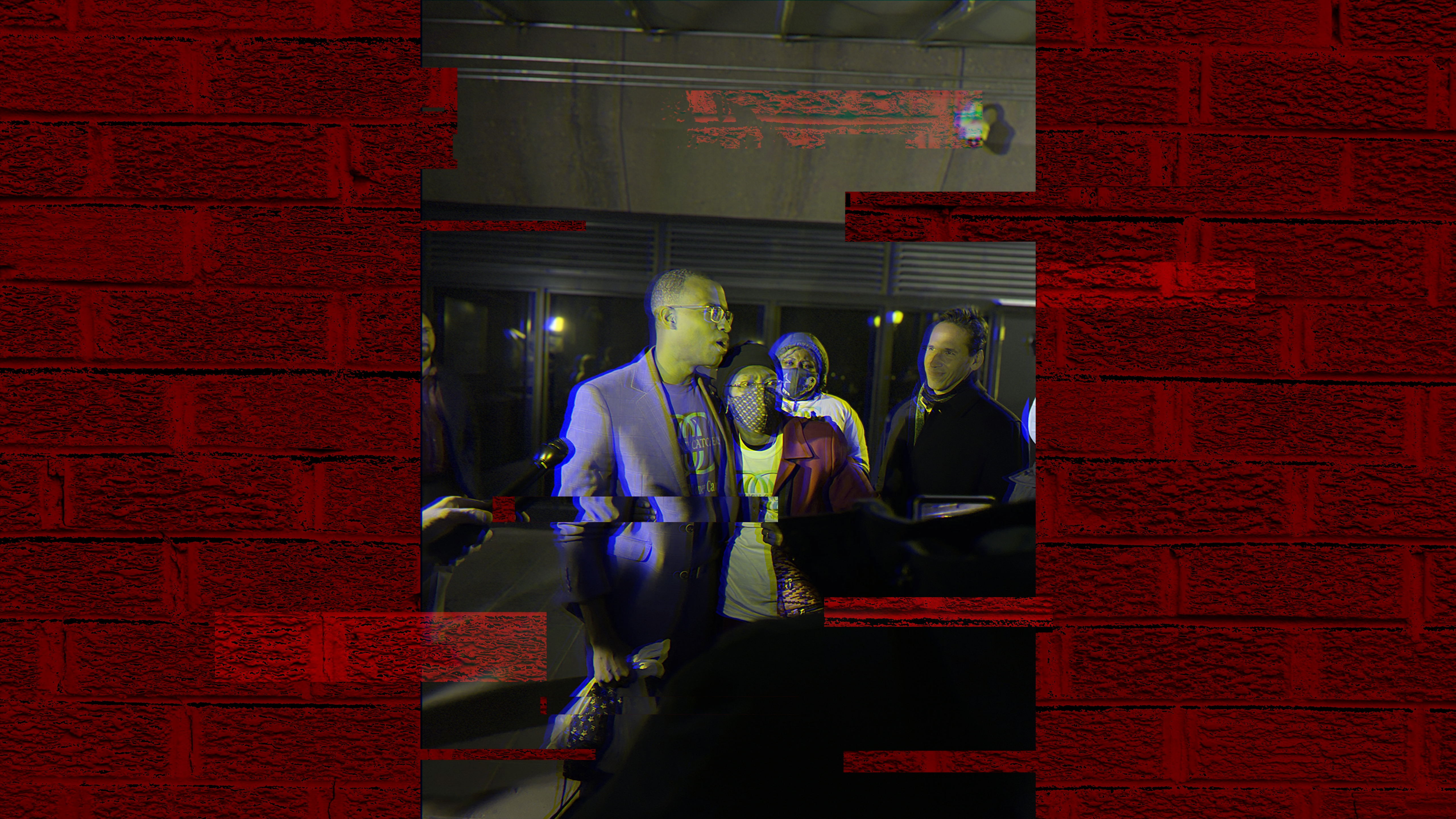

On a chilly November evening, a side door of the D.C. Jail swings open. The crowd just outside erupts into cheers. A woman, nearly shaking with excitement, approaches the open door. Out steps a guard, followed by the man they all came to see: Joel Castón, 44 and incarcerated since 18, coming home.

Castón takes his first step out of the jail as a free man and kneels. He springs back up and tightly hugs the woman, his mother. Everyone around him applauds, including the guards that came out with him.

It’s the first free step he’s taken in 27 years. But another first has brought the crowd along to witness his release: Castón was the first incarcerated person to win a D.C. election, and is now the first to be released while holding city office.

“I was immediately overwhelmed and overjoyed,” Castón wrote in an email to the Voice about the night of his release. “As I said when I left the jail, it hasn’t been 27 years of waiting to go home, it’s been 27 years preparing myself to never come back to prison again.”

Castón’s preparation was extensive. While incarcerated, he got his GED diploma, took university classes with Georgetown’s Prison Scholars Program (PSP), taught himself five languages, became a financial literacy instructor, led religious services, and more.

When D.C. gave incarcerated people the right to vote in July 2020, empowering those in the D.C. Jail to fill its empty Advisory Neighborhood Commission (ANC) seat, Castón won a special election to become 7F07’s commissioner. He was given a desk, a computer, and up to eight hours a day to work on his ANC duties.

Now, over six months after being sworn in, his release means a new desk, a new computer, and all the time he wants to do whatever he likes whenever he likes. But Castón has no plans to change his ANC work anytime soon.

Castón has had a long road to release, in which the ANC seat was only the most recent turn. According to Marc Howard, the director of Georgetown’s Prison and Justice Initiative (PJI), Castón has always been a leader.

“He was already extraordinary, frankly, when I met him,” Howard said. Castón took several classes in the Prison Scholars Program starting four years ago, often attending weekly guest lectures. “Basically every visitor and guest speaker who came would walk out saying, ‘Wow, that guy’s amazing,’” he added. “Some of them would say, ‘Can I hire him when he gets out?’”

But Castón had already created his own work well before getting out. In 2018, he and another resident of the D.C. Jail, Michael Woody, founded the Young Men Emerging (YME) program, which serves as a residential unit and mentorship program pairing long-term residents with newly incarcerated young adults.

Tyrone Walker, one of the first YME mentors alongside Castón and Woody, said that the program was one of the most rewarding things he’d ever done, in part because of how much of himself he could see in the mentees.

“I remembered when I was them, and I could help them, I wanted to help them, to chase their dreams,” Walker said. “And to achieve, to actually get there. That’s something that none of us mentors got, not me, not Joel, not anybody.”

Walker added that while most of the logistics of setting up the program were left to the residents, Castón and Woody were extremely dedicated and worked tirelessly to make sure it became a reality.

“When he cares about something, you better look out,” Walker said of Castón. “He’s a force to be reckoned with.”

Castón brought that same dedication to his push for an ANC seat, which had been vacant since its creation in 2012. Castón’s first attempt at election in November 2020 was stopped short by a voter registration error that incorrectly disqualified him as a non-resident. He ran again in June of 2021 against four other candidates.

Commissioners are tasked with representing their district primarily by advising the city government on public policy that affects their direct constituents. They often speak at D.C. Council meetings and hold monthly Commission meetings where neighborhood residents can raise questions. Castón’s district, like most ANC districts, is small — so small, that it contains just three residential buildings.

In a campaign video filmed by the Department of Corrections, Castón welcomed new residents of the recently opened Park Kennedy apartment complex and promised to weigh the concerns of residents of the Harriet Tubman Women’s Shelter.

And to residents of the jail, Castón declared: “My platform will be used to restore the dignity of incarcerated people, so that we will no longer be judged by our worst mistake.”

In November of 2021, as part of this effort of restoration, Castón spoke to the D.C. Council’s Committee on the Judiciary and Public Safety in a roundtable hearing about the conditions in the D.C. Jail after a report found them unsatisfactory and about 300 residents were subsequently moved to federal prisons elsewhere.

Castón noted at the hearing that those directly impacted by the conditions, his incarcerated constituents, were unable to join him in speaking for themselves and telling their stories firsthand. He was able to attend as the commissioner, zooming in from the D.C. Jail with Georgetown’s Riggs Library as his virtual background, only “because technology has leveled the playing field and allowed [him] to participate.”

“I think we need to scale that so we can hear from more of the people on the inside,” Castón said in November. “Although I’m happy to be an elected official and represent my constituents, I would be more happy if they were here.”

In lieu of that, Castón stressed his particular value as a commissioner who was, at the time, one of the incarcerated people that was experiencing the conditions firsthand. “I can tell you, the reason this thing is so fresh to me is because it’s in my veins, it’s the only thing I know,” Castón said at the hearing. “I’ve been living and sleeping and thinking about imprisonment for 27 calendar years.”

Going forward, as D.C. redraws the borders of Single Member Districts (SMD) through redistricting, Castón said the Council ought to “make sure there’s always an incarcerated person representing incarcerated people.”

Though he is no longer incarcerated with some of his constituents, Castón is now residing nearby and plans to stay in touch with as many people as he can, continuing to use his personal history and network of connections to be an advocate for his former peers in the D.C. Jail. However, because of visitation restrictions during the pandemic, Castón will have to do so from afar, which may pose new challenges, as his administrative assistant Frances Trousdale (COL ’22) wrote in an email to the Voice.

“It’s unclear how the communication will operate, particularly as the jail still has some COVID restrictions in place, but Joel will certainly be able to stay in touch through phone calls,” Trousdale wrote. “In addition, he regularly receives emails from incarcerated individuals as well as family members on their behalf.”

Castón’s release also means he’ll be able to visit the Park Kennedy complex and the women’s shelter, as well as attend Commission 7F—the Commission Castón’s SMD fits within—meetings in person. In 7F’s monthly public meeting on Jan. 18, Castón was sworn in as the commission’s treasurer.

During the virtual meeting, Castón spoke about Hill East construction projects that will add more housing in his SMD, as well as a presentation from the D.C. Sentencing Commission that he critiqued as “mimicking federal sentencing guideline schemes which, currently, is why the United States as a nation has been extremely punitive and has not taken into consideration rehabilitation efforts.”

Castón is also working as a consultant at the Justice and Policy Institute (JPI) to not only serve his constituents, but to spread restorative opportunities like the YME program to other incarcerated populations, which he believes will “empower every incarcerated individual and give them a space to live up to their highest potential.”

“This rehabilitative system completely rethinks how our country views incarceration,” Castón wrote. “As I’m assuming a role as a consultant with JPI, I am working to bring this legacy to jails around the country.”

Specifically, Castón and JPI have begun to assist the New York City Department of Corrections with the establishment of a program similar to the YME on Rikers Island. According to Marc Schindler, executive director of the JPI, Castón and the other early YME mentors have been consulting on that project from the jail for some time.

“I expect that Joel will continue in that role, now that he’s back in the community,” Schindler said in an interview with the Voice. “I also expect that he’ll work with us on some other projects moving forward, where he has an interest and we have an interest, and collaborating in that way.”

One project Castón plans to pursue has to do with the reason he was able to get elected in the first place: securing the right to vote for incarcerated people. Only in D.C., Maine and Vermont is that right guaranteed while individuals are incarcerated. It is critical that people like Castón and the JPI continue to fight for it across the country, Howard said.

“In terms of the right to vote and to have citizenship rights, [Castón] really is a shining example of why that’s important,” Howard said. But only in D.C. is it probable for this right to vote to translate to a seat in the government. “It’s obviously hard to run a campaign from prison, and this was a neighborhood commissioner seat for an area that really primarily includes the D.C. Jail.”

The circumstances that allowed Castón to get elected are unique. SMDs are a more granular system of representation than most cities have, and few cities have detention facilities within their borders from which incarcerated people could cast votes. But just because a perfect storm got Castón elected, Schindler said, doesn’t mean there aren’t others currently incarcerated with the same propensity and ambition.

“We shouldn’t be fooled into thinking that there are not literally thousands, tens of thousands, probably hundreds of thousands of people incarcerated today who, if given the opportunity, if given the support, can flourish and lead just like Joel is doing,” Schindler said. “He’s a remarkable person, but he’s not the only remarkable person.”

Castón has shown that when incarcerated people are given the opportunity to participate in civic life, they have much to contribute, Schindler said. According to him, Castón is an example, not an outlier. Barriers like the inability to vote keep others across the country from achieving what Castón has, and these barriers are what he will be working to knock down in his role both on the ANC and with the JPI.

“Policies have to be rewritten to allow someone like me to qualify to be a politician, to be an investor, to be a banker,” Castón wrote in a column after his release. “If we can do that, then we can open the floodgate. We’re an asset, not a liability.”

The policies Castón aims to rewrite bar people across the country from voting, receiving higher education, and more because of their status as incarcerated people. Decades of discrimination in the criminal justice system have filled prisons disproportionately with people of color, linking incarceration and racial injustice in this country.

According to Pew Research Center analysis of 2017 census data, 33 percent of those incarcerated in the prison system are Black, while the country at large is one 12 percent. Hispanic people are 7 points overrepresented in prisons, while white people make up 34 percent less of the prison population than they do in the country at large. This disparity has always been the case, if not worse.

That gap inextricably links criminal justice reform with racial justice, and steps that empower incarcerated people is a step for racial equity as well. It gives Castón’s policy work an added layer of importance, and his unprecedented achievement an added layer of significance.

But before he can tackle these issues head-on as a consultant at the JPI, Castón must adjust to his life as a free man. Walker, who works as the Director of Re-entry Services for the PJI, stressed that this need must come first in every re-entry.

“His most important job is to reacclimate himself to the community,” Walker said. Once Castón has done that, “he will be tackling the issues of his constituents. And he will be making an impact in his community.”

“We’re going to see a whole lot of things change,” he added.

According to Trousdale, Castón took time off until Jan. 5 to reacclimate before returning to his ANC duties.

Howard said that though Castón’s release might be historic because of his office and what Castón will do next, the most meaningful part for any incarcerated person will always be the moment of the release itself.

“It’s never happened before, somebody leaving prison with an elected position,” Howard said of Castón.

“But honestly, all releases are special,” he added. “It’s always a magical moment to see somebody leave prison, especially after decades, and walk into the arms of their mother.”

test