I tend to avoid shows about teenagers. Even when I was a teen, they rarely appealed to me, and this distaste has only grown as I’ve entered young adulthood.

The teen shows I do watch, then, are carefully selected. The sort of recommendations I end up taking are those billed as “raw” and “real,” the kind that people rave about online for capturing the ‘true teen experience’—the way people talk about Euphoria, the second season of which is ongoing. The plots are supposedly driven by genuine interpersonal conflict, and the characters defined by nuance and depth. And, for the most part, I’ve been impressed. But, despite how real and groundbreaking these shows are supposed to be, they’re never quite able to overcome my aversion to teen shows. And that’s for one simple reason: the casting.

Invariably (at this point it’s almost a staple of the genre in itself), the lead actors in shows meant for and focusing on teens are comically older than their characters, regardless of how valiantly the showrunners attempt to capture teen realism. This phenomenon isn’t new: The classic archetypical teenage character, Rebel Without a Cause’s Jim Stark, was played by a 24-year-old James Dean in 1955. But the trend has only become more prevalent as media for and about teenagers grows in popularity.

It’s overwhelmingly common for actors playing teens to range throughout their twenties. Actors Zendaya, Sydney Sweeney, and Jacob Elordi, among others playing older teenagers in Euphoria, ranged from 20 to 24 during the first season. And it isn’t as though casting directors take pains to select actors who look much younger than they are—in Euphoria, none of the actors could pass for a high school senior. Euphoria is merely one example of how teen shows have largely abandoned the idea of shaping their casts around realism for the characters’ ages. Instead, the image of a teenager has morphed into something more closely resembling a recent college graduate. Audiences have learned to accept it so much that they hardly notice at all; that’s just the way it is.

But it shouldn’t be. The tendency for visibly mature adults to be cast as teenagers is often written off as a mere annoyance for younger audiences, if that. Yet its potential effects mean it shouldn’t be discounted.

Watching Euphoria when it first came out, as an 18-year-old fresh high school graduate, I was older than the characters but still years younger than their actors. My body was long and somewhat lanky, with the slight awkwardness and angles that I’m still outgrowing. It was hard to ignore how much more physically developed the characters, supposedly two grades below me, were. I’ve always had a good deal of confidence in how I look, but it was hard not to wonder whether maybe what I was seeing onscreen was how I was supposed to look—or whether it was how I was supposed to have looked two years prior, putting me even further behind.

Anyone doubting the true difference between a 23-year-old and 16-year-old’s appearance need only watch Storm Reid—an actual 16-year-old—in Euphoria, who plays the main character’s younger, middle-school-aged sister. An actual teenage viewer will likely more closely resemble this young character—whose youth is a prominent plot point—than those who are supposedly their own age, a phenomenon which exacerbates the effects of aged-up casting.

Further issues are created because the mismatch between the age of actors and their characters are rarely at the forefront of viewers’ minds. The shows weren’t sending the message that I looked too young, but that I just looked bad—even characters much younger than I was had fully developed chests, large hip-to-waist ratios, and mature faces. It’s always possible, as a teenager, to rationalize that any attractive features seen in adult characters but lacking in oneself are just things one needs to grow into; when these features are seen even in supposed teenagers, this possibility is removed. Though a careful awareness of the actual ages of the actors helped me avoid internalizing these messages, I found myself slightly affected by them. I can’t help but wonder if maybe, were I just slightly less attuned to the disconnect between the ages of the characters and of their actors, or a younger audience member, this effect would have been even greater.

The trouble with such casting practices doesn’t stop there, though; it also affects adult viewers.

For many adults, teenage characters in media represent the only contact they have with high schoolers. For those without younger siblings or children of their own, it’s not uncommon for their view of the contemporary teenager to be shaped by what they see on the screen. And when adults masquerading as children dominate on-screen representation, it’s not hard to see how the picture they can form of what a teenager truly is can easily be distorted.

Especially when it comes to sex.

The topic of sex is almost unavoidable when discussing the modern teen drama. Even as shows push the envelope on just how sexually explicit they can be, the more mild ones, too, tend to at least touch on it. Which makes perfect sense—teenage years are a time of change, and the discovery of a newfound sense of sexuality is a hallmark of that stage of life. But, when portrayed by fully mature adults, even the most insightful and valuable explorations of the topic can present problems. When characters with the faces and bodies of conventionally-attractive adults explore sexuality on screen, not only does it provide confusing signals to teenage viewers about what level of sexual maturity is expected of them, it creates a problematic dynamic wherein adult viewers are attracted to adult bodies inhabited by, narratively speaking, children.

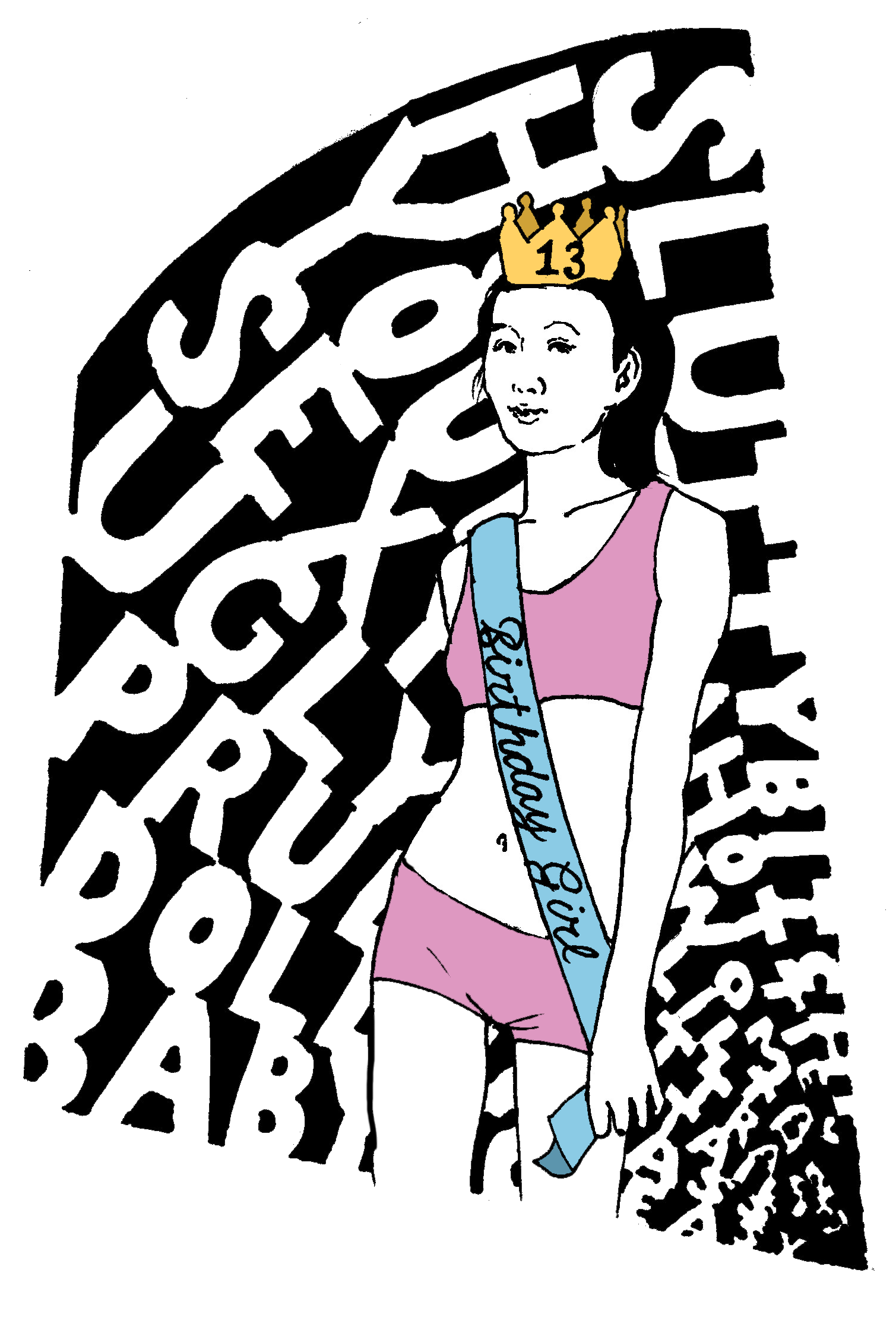

Now, I don’t mean to say that the practice of casting adults to play minors is directly leading to an immoral sexual attraction to underage girls. Such a claim would be unsupportable. But mass sexualization of teenagers—especially teenage girls—is real. From a then-17-year-old Britney Spears dressed as a sexy schoolgirl to the phenomenon of “countdown clocks” to underage celebrities’ 18th birthdays, the view of teenagers as sexually appealing to adults is ubiquitous in modern pop culture. While the casting of adults as teens did not cause this trend, it enables audiences to view teenage characters as both attractive and old enough to validate that attraction, which does little to discourage their sexualization.

All of this is to say that, regardless of which segment of a show’s audience we consider, the trend of casting adults to play teens is more than merely annoying—it has the potential for significant harm.

But, of course, there are barriers to casting actual teenagers. One of the most obvious of these is that, with actors under 18, a showrunner’s freedom to portray explicit content is severely hampered.

This hampering is a genuine concern in terms of the artificial limitations it places on a showrunner’s ability to achieve an artistic vision, but we need to ask ourselves what we actually lose by placing these limitations. While scenes involving sexual content can hold genuine value—especially in the context of a show exploring the inner world of teenagers—a startlingly high proportion of the sexual content in shows about teens exists merely to exploit the supposedly teenage body.

Consider, for example, a particularly famous 2008 run of posters for the show Gossip Girl, which featured supposedly negative reviews such as one calling the show “mind-blowingly inappropriate” alongside highly suggestive, mostly nude stills of the show’s teenage characters in intimate moments. Though Gossip Girl was strengthened by its exploration of sex, the way it took advantage of the actors’ statuses as mature adults clearly served as an exploitative advertising trick, coaxing viewers to watch the show with the promise of sexy, if underage, characters.

I don’t intend to claim that there could never occur an instance in which, in order to meaningfully explore something worth exploring, it would be necessary to shoot a sexual scene in such a way that an underage actor couldn’t be included. But the difference between a valuable scene in which a character explores their sexuality and an exploitative one that takes advantage of the supposedly teenage body can be as simple as how things are shot or how much skin is shown.

The very first shot of Netflix’s Sex Education, for example, ends with the camera focus squarely on the nude bodies of two teenage characters in the act of having sex. The show is, as the name suggests, very much concerned with its characters’ sex lives, but the total nudity of two underage characters was by no means neccessary and served only to tip the otherwise very good show in the direction of the sexualization of teenagers so common in the medium. Though there may be some cases in which the casting of adults is necessary in order to achieve an artistic goal that requires some level of explicitness, in many cases, working around the limitations of underage actors would actually improve the quality of the show by moving it away from the sexualization of young characters who are, in essence, children.

And there are, of course, purely logistical issues. Minors have school and are only permitted to work limited hours in many states. But these challenges are far from insurmountable, seeing as there are already examples of minors working in the television industry—the younger sister in Euphoria was played by a genuine teenager, as are the majority of characters in shows aimed at young kids, such as on Disney channel. And even if these logistical issues prove to be too much, the least casting directors could do is cast adult actors who look young for their age. It’s not ideal, but I’d rather see a Euphoria full of young-looking Zendayas than the one we have, full of adult actors good at their jobs but not teenage in the slightest.

It’s hard, noticing all this, to find teenage-focused shows I can truly and wholeheartedly enjoy. For all the cinematic beauty of Euphoria and the insightful emotional heart of Sex Education, I can’t watch them without the uncomfortable awareness of the mismatched age in the casting. It’s annoying, sure, but it’s more than that; these shows have real, significant effects on the world around them, and the way directors make casting decisions does too.

So, no, shows for and about teenagers have never been overly appealing to me. But maybe, were the industry standard to shift to something a little more genuine and a little less harmful, I’d finally pick up those shows I’ve shunned for so long.