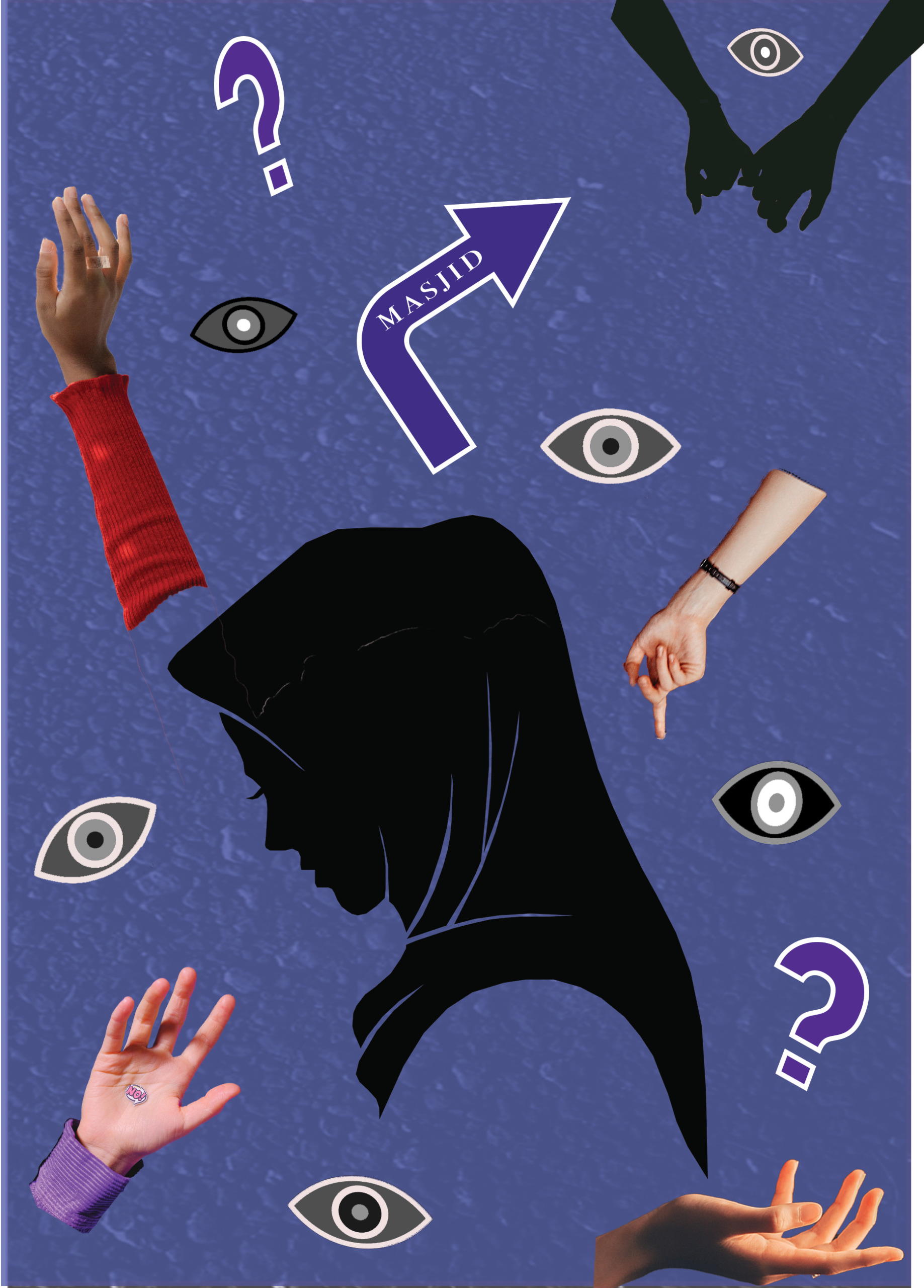

By the end of my first semester, I could already count a handful of times a stranger had stopped me on the sidewalk, asking for directions to the campus mosque. I’m a hijabi, so asking me makes sense—who else passing by Reiss could answer? People who stop me hold certain expectations about what I should know—and in cases like this, I’m able to not only meet but surpass those expectations. I could give you directions to the masjid from pretty much any spot on campus. I know it has a one-way staircase leading to the VCW patio. I know it’s home to a Quran with a sticker reading “property of GW MSA, do not remove.” I know three dried-up date seeds have been sitting on the back shelf of its storage closet for who knows how long.

But this question forces me to wonder what people expect of me solely because of the way I present myself—their assumptions about what I know and how I think.

Wearing hijab is a conscious decision that allows people to know my religion at first glance. Hijabis are like the lighthouses of Muslims: We’re easy to see and people gravitate towards us when they have an Islam-related question. Being a recognizable representative of my religion is a responsibility that I know comes with wearing hijab, but its implications aren’t necessarily negative. It pushes me to learn more about my faith while exerting positive pressure to strengthen my spirituality. But in the end, the only thing that will truly make me more religious is my own desire. Eventually, these pressures outlast their usefulness, and the continuously high expectations for hijabis become unattainable and discouraging—unbearable, even.

And these expectations are everywhere. They can manifest as anything from simple questions about directions to complex grillings about the history of Islamic empires. They’re an English tutor, a hijabi herself, expecting me to understand the nuances of Arabic (which I do not speak). But hijabis are not walking textbooks. We don’t know every detail about our religion and we don’t all speak Arabic. When people equate wearing hijab to knowing everything about Islam, I want to meet their expectation even if it’s impossible. And when I can’t, I feel—at least a little bit—like a failure. I feel like a bad Muslim and chide myself for not knowing the answer to every possible question.

The root of this issue is the idea that hijabis are somehow bottomless sources of information. People seem to think that if someone is committed enough to wear hijab, they must also have the education and experience that generates expert knowledge. And here we encounter a second problem: Expecting hijabis to know more goes hand-in-hand with expecting non-hijabis to know less.

Pitting Muslim women against each other in a spiritual hierarchy is one of my biggest pet peeves. Just because a woman wears hijab doesn’t mean she is automatically more religious, or a “better Muslim,” than one who doesn’t. While unrealistic expectations for hijabis put unreasonable pressure on them, it also invalidates other Muslim women. It reinforces the idea that non-hijabis are somehow less practicing, less knowledgeable, less informed—less Muslim. This mentality is harmful for all Muslim women, depressing their innate drive to foster their spirituality while simulatenously invalidating their identity as Muslims. Hijabis feel discouraged when expectations for them are too high and subsequent feelings of incompetence undermine their confidence in their faith, while non-hijabis feel discouraged and ignored as Muslims when expectations for them are too low.

But while many presumptions focus on what hijabis know, others concern what and how we think. These are a bit harder to pinpoint because they manifest in smaller, almost invisible, moments. It’s couples normally comfortable with PDA dropping each other’s hands when I come by. It’s close friends excluding me from conversations about their love lives as we sit at the same lunch table. It’s a well-meaning friend beginning a story about deer hunting with “I don’t mean to offend you because of your religion, but…” (To this day, I do not understand how this would be offensive, but I digress).

People assume that hijabis live in a separate universe—our physical expression of faith is interpreted as an indicator that we are fundamentally incompatible with the time period we live in. It seems people’s schemas of Muslims, and hijabis, are built around what they’ve read in world history textbooks and are not representative of the modern diverse community. They assume hijabis are immune to the typical college-student struggles. Or that we’d be offended by the way others choose to live their lives. It’s as if we somehow exist in the 17th century: We have no understanding of pop culture or the realities of college life, and we of course couldn’t possibly have a Tik Tok dance memorized. We are expected to know everything about our religion yet nothing about anything else. This helps label hijabis as “others” and enables our exclusion from our broader community of peers.

These assumptions are exasperating. I’m a 19-year-old college student, but my classmates see me as a conservative grandma who has no interest in the shenanigans of young people these days. I automatically feel unwelcome in social spaces, making me hesitant to enter them or meet new people.

And this matters: Assumptions about hijabis have more weight than you imagine. It’s unfair to expect us to know everything and it’s unfair to expect us to know nothing. Interacting with us the same way you would interact with anybody else allows us to simply exist. It frees us up to set our own religious expectations for ourselves and fights against the invalidation of non-hijabi Muslim women.

So if there’s a hijabi in your Intro to Islam class, don’t expect her to get the best grade. Don’t make her be the spokesperson for two billion Muslims she’s never met. If you have a burning question about Islam, maybe think twice before springing it on an unsuspecting hijabi. Interreligious understanding and education is important—it makes us all feel valued in a diverse community while respecting our differences, but individual members of the Muslim community should not be responsible for providing this education to you. While we appreciate you trying to learn more about our faith, we also appreciate you saving your questions for a more appropriate time, place, and person (like a qualified religious leader). Or even better, start by trying to find the answer yourself. And if you can’t find a good starting point for your search, that’s one thing you can ask me. I know where the masjid is.