One February evening in 2017, I caught myself gripping the couch while watching the Grammys, jaw slackening as I watched Beyoncé lose Album of the Year (again). Somehow the failure of Lemonade—then her magnum opus—to triumph Adele’s splendid but mostly ordinary 25 felt lament-worthy. Not simply that it reified the long-held race problem the Grammys has always had, but also because it felt almost impossible for Beyoncé to surpass Lemonade in quality and cultural credo. How can she go anywhere from here but down, I thought faithlessly. And what of her legacy now?

Of course, even before the late July release of Renaissance, her follow up to Lemonade, Beyoncé has moved her chess pieces around to only deepen the mythos of her three-decade long career—especially in its Blackness. Her Coachella headliner in 2018 (“Beychella”) relished in the special—but increasingly precarious—joys of historically Black colleges and universities. A collaborative project with husband JAY-Z (Everything is Love [2018]) saw her fullest embrace of hip-hop. Her gradual adoption of pan-African aesthetics over the last decade (see “Countdown” borrowing from Fela Kuti in 2012) came to a hilt as a curated soundtrack album for the live-action Lion King (2019), waist-deep in Afrobeats and Afropop features. In all, Beyoncé kept a strong hold on her status as a vanguard, unblinkingly Black and proud.

But it’s on Renaissance where Beyoncé proves there’s no need to top herself—she instead transforms the musical geography altogether. And in a new ocean we swim: Renaissance feels peerless among her 250-song discography in its embrace of dance, house, and disco. With 16 tracks made for movement, the record is her danciest yet. Front to back, these are songs for ass throwing (“CHURCH GIRL,” gospel influence aside), dips, twirls, and every kick-ball-change you can think of. A choreographer’s wet dream.

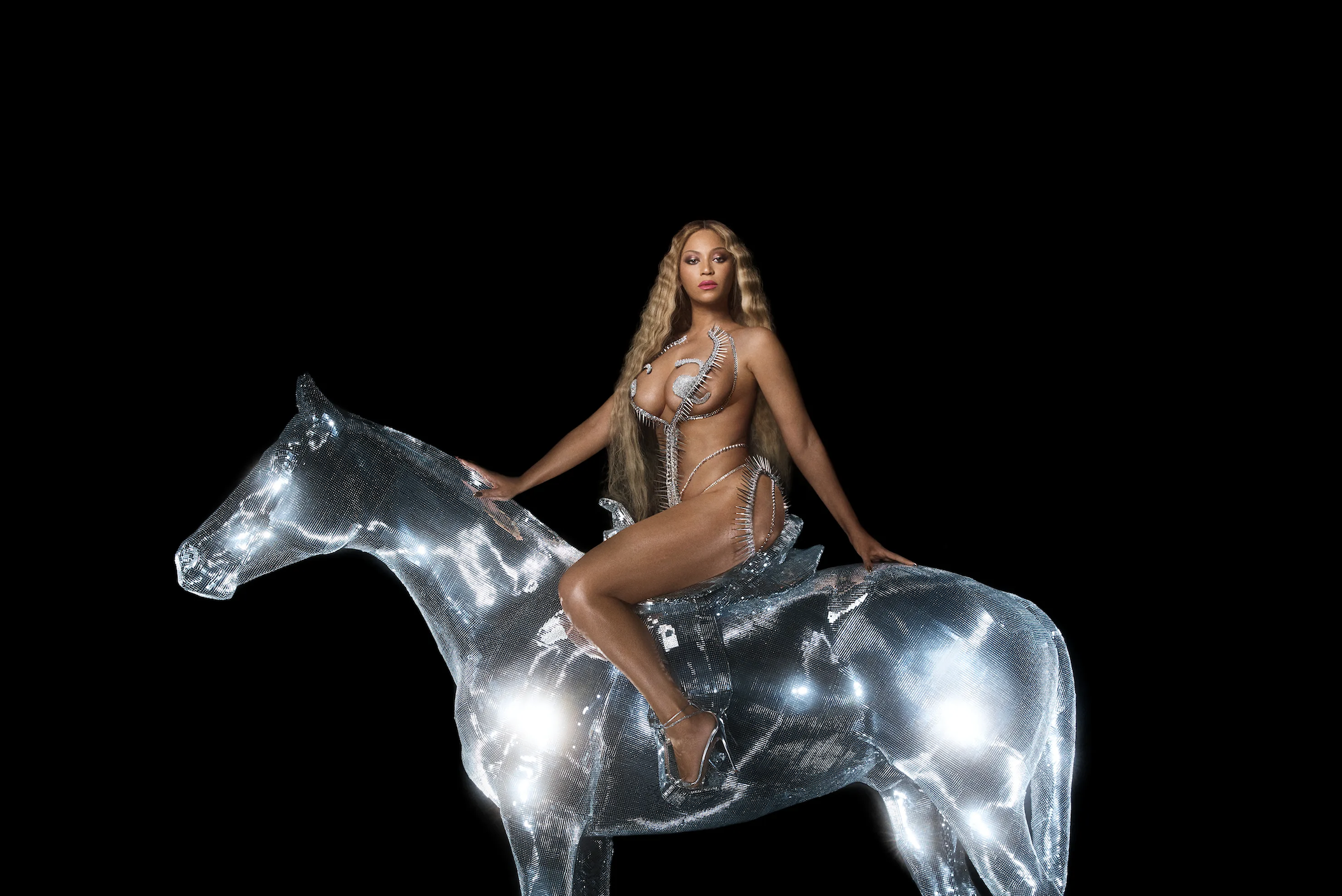

Appropriately, Renaissance is also her sexiest record yet. While the inclusion of “Partition” and “Rocket” on Beyoncé 9 years ago felt almost naughty, even radical, as a new mother brazenly reclaimed sex symbolhood, Renaissance is not so coquettish. Rather, the sexualized body is both the record’s chief aesthetic and target. On “HEATED,” “THIQUE,” and the deceptively-titled “AMERICA HAS A PROBLEM” (the problem in question is, in fact, that she’s too sexy—not, say, state-sanctioned violence), desire burns hot and without metaphor.

There’s no shortage of pure musical excellence embedded in the album, either. Six-minute odyssey “VIRGO’S GROOVE” sees Bey deliver some jaw-dropping vocals—the galactic riffs on lines like “You’re the love of my life” are so good that it’s easy to forgive the borderline cheugy lyricism. Copying the career-best vocal gymnastics on “PLASTIC OFF THE SOFA” is now a TikTok challenge everyone from Chloë to Jojo has hopped onto.

Given it seems made for the dancefloor, it’s easy to think of Renaissance as a post-pandemic album—and perhaps it’s true, though the “post” prefix is a misnomer for a disease still ravaging the country. Yet the political and cultural headspace in cities across America seems to have moved on, however individualistically, sending capacity and masking policies to the wastebasket. The result is a culture two-years-starved for connection in communal space, with so many choosing to indulge in the luxury of pleasure despite the complicated—even reckless—moral psychology involved. The philosophy of Renaissance responds to all this by saying, plainly: Dance, and everything else can come later.

Indeed, few artists truly convene community like Beyoncé—especially for Black listeners. There’s a Beyoncé album for every era of my life, a friend texted once. Each record is an experience both personal and collective, where the record so accurately reflects the shared emotional mood of the moment. Renaissance follows: Every good DJ across the country is spinning the whole record silly (more of “CUFF IT,” please); I am hopeful that the back-to-school college parties at Georgetown and beyond will blast “ALIEN SUPERSTAR” so we might all scream UNIQUE!!! skyward in unison.

The long-term legacy of Renaissance might be more complex than simply collective revelry. While mainstream media labeled lead single “BREAK MY SOUL” a Great Resignation anthem for eschewing grind culture in favor of catharsis (“Release your job, release the time!”), the lynchpin of the album still seems to be material capitalism. It’s a fierce line, but there’s only so many times you can holler “It should cost a billion dollars to look this good!” in “PURE/HONEY” before the thought emerges: Should it? The album glamorizes being “in your bag” (with those literal Birkins in storage)—unsurprising for a woman known for her aspiration to join the billionaire class. It begs the question whether the musical elite will ever really be able to speak (and act) in line with the working class.

Renaissance also did not drop without controversy—in its deployment of a word some decried as an ableist slur but also sometimes used more innocuously in AAVE, as well as becoming part of an ongoing debate about sampling. The album liner notes stirred pots when Kelis’ “Milkshake” appeared to be sampled without her permission—largely because the Neptunes own all the production credits. A critical obsession with the dozens of people credited on Renaissance (Robin S., Sheila E., the Clark Sisters, and more) also emerged, largely from non-Black critics failing to acknowledge that meticulous sample curation is a worldbuilding tool itself, building intergenerational and cross-genre relationships. Beyoncé ended up making surgical repairs on streaming platforms, removing the criticized term and the Kelis sample. I anticipate these post hoc edits will become more commonplace in the coming years to fix “mistakes,” with artists seamlessly sewing over records with most listeners none the wiser, and I’d like meaningful debates about artistic ownership to continue.

Most of all, I’m hoping Renaissance forces our culture to better embrace intersecting identities. Above all else, Renaissance is a love letter to Black queer communities, underground ballroom cultures especially. Legends like Kevin Aviance, Big Freedia, Moi Renee (“Miss Honey!”) make central appearances, and queer Black producers and writers span the record (Syd from The Internet, Honey Dijon, 070 Shake, etc.). “I’m comfortable in my skin,” she declares simply on “COZY.” A queer anthem—with “SUPERSTAR”—if I’ve ever heard one.

The American sociopolitical context that Black queerness is situated in, however, is not all vogue and glamour, though important firewalls. LGBTQ+ rights—the assault of which will hurt Black, disabled, and trans communities hardest—are under increasing pressure, with legislation attacking vital trans medical care and the mere discussion of gay people in schoolbooks. While we call the bacchanalia that is Beyoncé’s Renaissance to the floor, perhaps true legacy would mean adopting a politics of solidarity with the people who Renaissance celebrates the most—and wouldn’t exist without. For what good is joy if not lived by all?