“I believe as a group we feel the fund is not reparative justice and there is so much more the university has to do,” Julia Thomas (COL ’24), an organizer with Hoyas for Slavery Accountability (HASA) and a descendant of people enslaved by Georgetown, wrote when asked about her thoughts on Georgetown’s long-awaited reconciliation fund. She did not mince her words.

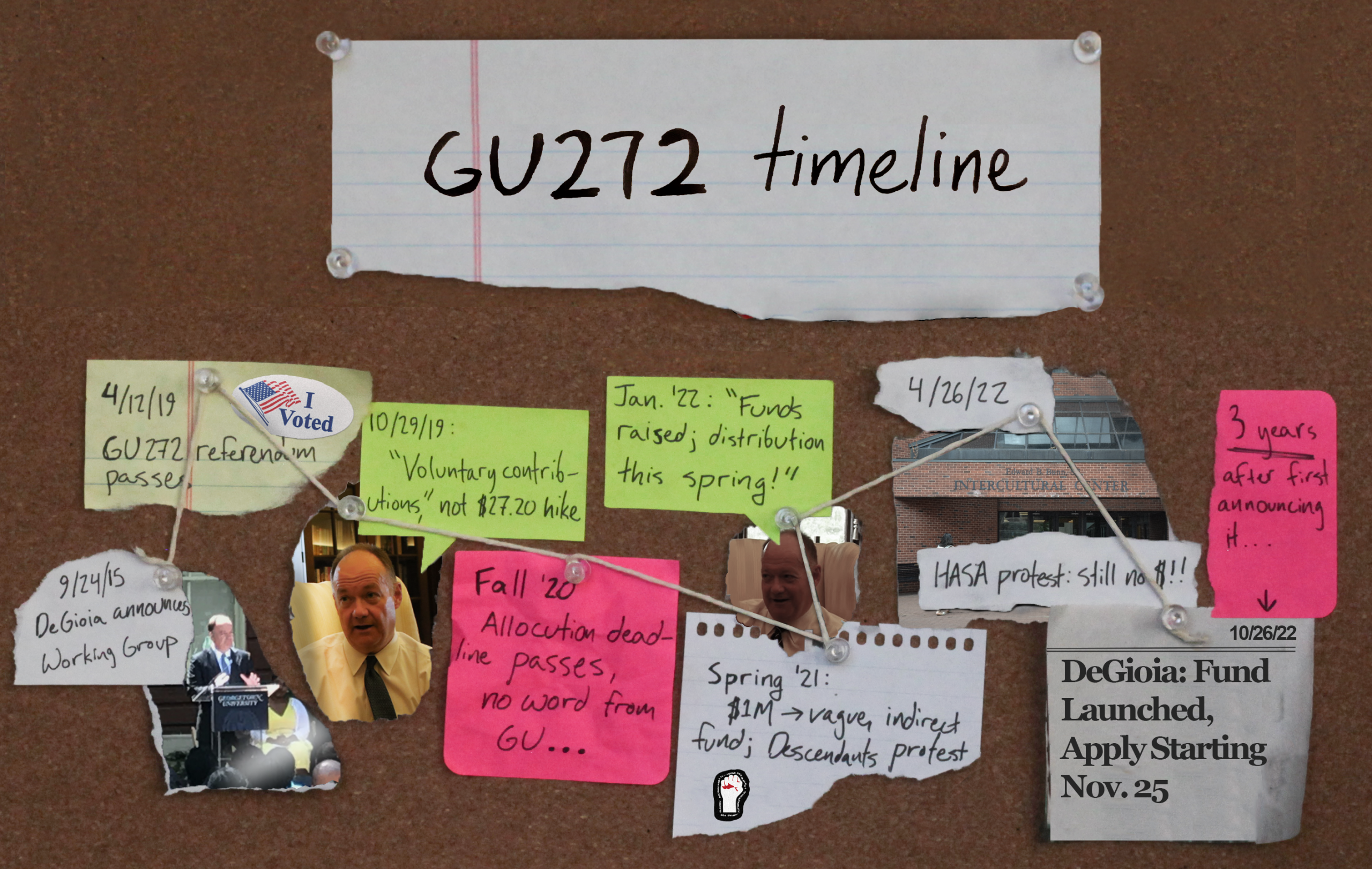

The Office of the President announced the Georgetown University Reconciliation Fund on Oct. 26, as a continuation of the efforts started by the 2019 undergraduate student referendum pushing for university action on reconciliations. Passing by a wide margin, the referendum called for financial reparations from students—those who benefit most from Georgetown’s history of enslavement—in the form of an extra $27.20 per semester added to tuition to go to the descendants of those the university enslaved. The referendum was originally intended for fall of 2020, but the administration has stalled implementation until now.

“The GU272 Referendum was created in light of Georgetown’s refusal to engage meaningfully with student and descendant initiatives for years prior,” Thomas wrote. “Designed to support an ongoing partnership between Georgetown’s student body and the descendant communities, the GU272 Referendum is a part of a larger movement for the redistribution of stolen capital to African descendants of formerly enslaved peoples.”

According to a university spokesperson, the fund awards $400,000 annually, raised via alumni donations, to “community based projects that aim to have an impact on Descendant communities whose ancestors were once enslaved on the Maryland Jesuit plantations.” It aims to give out roughly $200,000 per project application cycle with two cycles held per year, one in the fall and one in the spring.

Olivia Henry (COL ’24), another organizer for HASA, explained that the $400,000 is derived from the original total generated by adding $27.20 to each student’s tuition, as was proposed by the 2019 referendum. Sourcing the money from students—not from alumni donations, as the recently announced fund depends on—was a critical part of the referendum’s philosophy.

“It was genuinely meant to be a symbolic thing of students saying we want to increase our tuition so that it is known by all students and all university faculty that students are invested in financial reparations,” Henry said. She emphasized that because the number is symbolic ($27.20 for the 272+ individuals the university sold), it’s not derived from any measurable estimation of the impact of slavery, which a $400,000 fund cannot begin to address.

Additionally, activists in HASA feel a deep disappointment with the fund’s structure.

“The formation of a charitable fund in lieu of implementing the student referendum is an insufficient response to both the student body and descendant communities,” Thomas wrote.

Student activists also expressed skepticism about how exactly projects are selected, given the fund is supposed to be distributed via recommendations from the Student Awards Committee, a new group of students appointed by the university, who will work in tandem with the Descendant Advisory Committee. Advocates argue it is one of the ways the university absolves itself of truly engaging with descendants.

“Currently, the Georgetown reconciliation fund has both a group of students and descendants working together to decide what groups will be approved for funding and what groups will be denied. But because students are the ones who will be voting on this approval process for organizations, the university can use students as a scapegoat if any of these organizations turn out to not benefit descendant communities and cause harm in whatever way shape or form,” Henry said.

HASA activists see a charitable fund like this as a means of creating distance between the university administration and descendant communities—an attempt by Georgetown to quickly and neatly resolve its past harms and simultaneously relegate them to the past.

Student activists also expressed concern that the money from the fund may not go directly to descendants, as “community-based initiatives” include everything from developing a new preschool to health care initiatives, according to a university spokesperson. Both nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and independent individuals may apply for the Fund for advocacy projects, but projects cannot go towards personal use—potentially limiting direct benefit and agency for many descendants.

“They are able to fund non-profit NGOs that could potentially engage in very white savior-ist work to ‘benefit’ descendant communities, while Georgetown itself is not doing anything to support its descendants on campus or in surrounding areas,” Henry said.

The fight for reparative justice extends far beyond the newly announced fund. HASA has been continually involved with organizing mutual aid projects on campus, including a recently completed school supply drive that raised $335 for a school in Maringouin, La., according to Kessley Janvier (COL ’25). HASA is also working to address issues such as William Gaston’s recently publicized history of enslavement—the prominent Catholic North Carolina Supreme Court justice after whom Gaston Hall is named.

In Sept. of 2022, Professor John Mikhail at the Georgetown Law School published work shedding further light on Gaston having enslaved at least 163 people and advocated for judicial solutions to uphold slavery’s legality. HASA organizers have reached out to university administrators about what actions should be taken, including discussions of a name change and having President DeGioia send out Mikhail’s research in a university-wide email.

“We are passionately advocating for a name change of Gaston hall. We have been contacting the university and will be updating our Instagram with ways fellows students can help in the effort,” Thomas wrote.

HASA activists remain committed to fighting for reparations despite institutional stalling by the university and the Office of the President, which took over three years to only partially implement the 2019 referendum and remains silent on Gaston Hall, deeply disappointing descendants.

“This is a continuation of Georgetown’s commitment to white supremacy. Today it’s Gaston, tomorrow it’s something else,” Janvier said. “Our goal is to make it actively impossible for you to navigate this school without encountering how your privilege is directly at the cost of oppressed peoples.”

Editor’s Note: A correction was made to clarify that individuals—not just NGOs—can apply for the Fund.