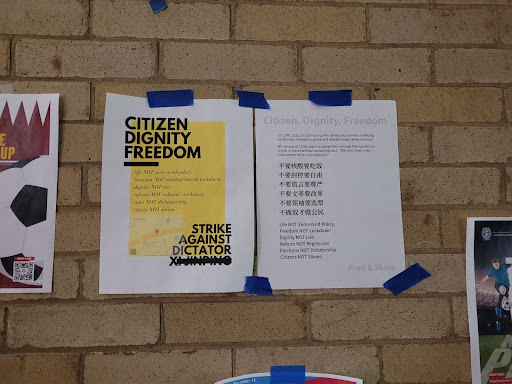

A series of anti-Xi Jinping posters quietly found its way onto the stairwells of Lauinger Library, the bulletin boards of Leavey Center, the walls of Village A, and other spaces around campus in late October. Broadly, these posters called for freedom, dignity, reform, and democracy in China.

The sudden appearance of these posters across Georgetown wasn’t a unique phenomenon: worldwide; some 352 universities—most of which in the U.S., the U.K., Australia, Japan, and Canada—witnessed similar movements.

The trigger behind this most recent wave of anti-Xi activism was a one-person protest in the outskirts of downtown Beijing on Oct. 13. A large banner hung from Sitong Bridge read: “We want food, not COVID-19 tests; freedom, not lockdown; dignity, not lies; reform, not regression; elections, not dictators; citizens, not enslaved people.” A separate banner hung next to the first one denounced Xi as a “dictator” and a “national traitor.”

The protest was in response to Xi’s precedent-breaking third term as president and general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that began on Oct. 23, a move that was only made possible after he abolished term limits back in 2018 and proclaimed himself “president for life.”

Even three years after the outbreak of the pandemic, China is still maintaining its strict zero-Covid policy, imposing sweeping lockdowns and testing wherever new cases arise. This has taken a toll on the economy, travel, and everyday life. In some cases, lockdowns have created widespread food shortages. Residents are often forced to endure hunger or suffer woeful conditions in quarantine camps.

The protestor, who has been dubbed “Bridge Man” (in a nod to the unidentified “Tank Man” in the Tiananmen Protest), was seen being taken away by the police, although there has been little information on his whereabouts since. The Chinese authorities have also adopted extensive measures to wipe this brief moment of dissent off the internet. Although the police swiftly took down the banner, its photographs had already spread throughout social media outside of China’s Great Firewall.

In an interview with the Voice, a Chinese student who wished to remain anonymous commented on the significance of this movement. “This is monumental,” said James, whose name has been changed in this article. “There’s never been a protest like this that has directly called out Xi. It’s very timely. I feel inspired that there’s a collective and spontaneous effort by Chinese international students to put these posters up in universities everywhere.”

Despite its wide reach, this movement doesn’t appear to be coordinated. “It’s probably an individual. Or at most maybe a couple of individuals. There definitely isn’t an organization behind it,” James said. “These posters have been circulating on dissident Instagram pages like @chinese.uncensored, where the account owners are also anonymous.”

James wasn’t the only student to find out about the Sitong protest through such Instagram pages. “I actually discussed with some of my friends on whether we should put the posters up around Georgetown. But we thought that it’d be too dangerous. There are other ways to raise awareness, like talking to the Voice,” Henry, another Chinese student who spoke on the condition of anonymity and whose name has also been changed, said.

“I hate thinking that I’d get reported by the [Chinese Students and Scholars Association]. It’s happened in other universities. It isn’t unknown that some people just get reported by their friends, and I hate thinking that my closest friends would report me,” Henry said. “My family is back [in China]. I love my family. Although I hate the system, I love my city. I have to be cautious.”

When inquired about who had put up these posters on campus, students speculated that it likely wasn’t an undergraduate, although none were aware of specific individuals or Georgetown organizations. “I noticed that the posters have been everywhere except the dorm buildings,” Henry said.

Furthermore, most of the posters were taken down just days after they had been put up. They disappeared the same way they had appeared—silently, mysteriously, and with no notable culprit.

Some Chinese students have expressed support for the Sitong Bridge protest, although worries about potential retribution or punitive punishment have limited their capacity to respond. “I think [the protestor] is a hero. I don’t want [my lack of action] to make it seem like I’m indifferent to what’s happening—I’m not. I’m just being practical. I respect what he did, but it’s stupid for him to throw his life away. There are better ways to protest the CCP,” Henry said.

This pragmatism was echoed by James. “Most middle-class students from China tend to be very practical. They either leave China, or stay in China and be silent,” he said.

Henry also stressed the importance of pragmatism in considering China’s political future. To him, not only is democracy currently untenable in China, but the attempt by the U.S. to force liberalization on China also implies that every country should aspire to be like the U.S.

“Realistically, everyone should give up on their hopes of imposing democracy on China. That’s just wishful thinking. First, that isn’t possible. China cannot become a democracy overnight. Second, that asserts the belief that the U.S. is superior when it isn’t. China should democratize incrementally on its own terms,” Henry said.

While Henry sought to shed light on the CCP’s oppressive regime, he emphasized the importance of approaching conversations about Chinese politics with care, nuance, and balance.

“I love democracy, freedom of speech, and civil rights. But to be honest, American democracy isn’t great. Trump was democratically elected. Rich people still dominate politics. I don’t like the Chinese leadership, but I don’t like the American leadership either.”

Despite these complicated dynamics in discourse surrounding politics in China and the U.S., both James and Henry hoped that these posters would be a starting point for constructive conversations about the CCP’s political oppression.

“There’s virtually no [Chinese media] coverage on [the Sitong Bridge protest]. Not enough people know about it, much less are talking about it,” James said. “It’s so important for people to know.”