Content warning: this article discusses suicide and self-harm.

It felt as though Smile’s (2022) marketing campaign was inescapable the month before its release. Instagram feeds were inundated with its ads, high-traffic YouTube channels promoted the film, and actors were even hired to sit in on nationally televised baseball games, sporting the film’s eerily distinctive smile. Embarrassing as it is, I was intrigued by the blatant corporate marketing. I found myself wondering how Smile’s premise surrounding trauma, seemingly lending itself to a smaller market film, could coexist with the very commercialized nature of the film’s promotion. With the popularization of A24 and similar production houses, I had hoped that the horror mainstream had adapted, creating space for less formulaic and more cerebral films. Perhaps this recent shift in consumer interest helps make sense of the seeming contradiction between Smile’s aggressive promotion and thematic scope.

At least, I had wished that this was the case. Upon viewing Smile, however, my hopes of a purposeful film were dashed. Smile is by no means a poorly crafted film; it excels in its intended role as an attention-grabbing, thrilling narrative that brought in sizable crowds. However, its potential to be more than a fun, but ultimately forgettable film, was squandered. Concerned foremost with its dramatic build-ups, jarring jumpscares, and unexpected turns, Smile epitomizes the modern box-office horror hit—a film that is more interested in profit than in exploring its conceptual potential. And a box-office hit it was, topping charts for two weeks following its release.

Smile follows psychiatrist Dr. Rose Cotter (Sosie Bacon), who is unwillingly thrust into a string of public suicides when an emergency room patient is brought to her. The patient (Caitlin Stasey), delirious from witnessing the graphic suicide of her university professor, takes her own life in front of Rose. Having experienced the trauma of this event, Rose begins to spiral into the very hysteric state that those preceding her in the string of suicides experience. This inherited trauma also reawakens within Rose a long-subdued unrest surrounding the death of her neglectful mother. From this starting point, it seems logical that Smile would tell a sobered tale of the struggles inherent to overcoming trauma.

As Rose descends into her madness, however, this perception of trauma, reflective of its actual function, begins to lose form. With the progression of the film, trauma procedurally takes on a more concrete design, functioning not as the abstract source of terror that we know it to be in reality but as a corporeal boogeyman—a classic slasher. Trauma begins leaving doors open in Rose’s home, directly speaking to her, and, in the final act, appearing to her as an apparition that she must physically battle.

It is here that Smile’s realized conceptual direction diverges from its potential. Though it could have made a profound and lasting statement about the condition of those facing trauma, the film fills its runtime with exposition and jumpscares. As well formulated as many of these jumpscares are, their ubiquity and precedence over the film’s thematic development blur its final message. Leaving the theater, I found myself wondering what, if any, conclusive statement on trauma was made. On one hand, Smile promotes the idea that trauma should be confronted, and ultimately overcome. In fact, it dedicates an entire subplot to the death of Rose’s mother and her reconciliation with the fact that she did nothing to prevent it. However, at times, this subplot felt utterly disregarded by and even at odds with the rest of the film.

Until the final act, we know very little of Rose’s experience with her mother. Here, the conflict of the subplot is both introduced and resolved in earnest, with Rose defeating the physical embodiment of trauma, freeing herself from its grasp. This resolution is short-lived, however, as it is quickly revealed that Rose’s triumph over trauma was only a vision.

Despite these flaws, Smile is an enjoyable watch. Yes, the film’s unrealized potential is frustrating, but in the end, it delivers an entertaining story loaded with compelling scares. The vehemence and oppressively grim presentation with which Smile treats trauma is also a surprising strength of the film; none—children, animals, and the audience—are spared from the pain of those it looms over. This ruthlessness is undoubtedly Smile’s strongest feature; in this aspect, at least, the film starts to get at its thematic potential.

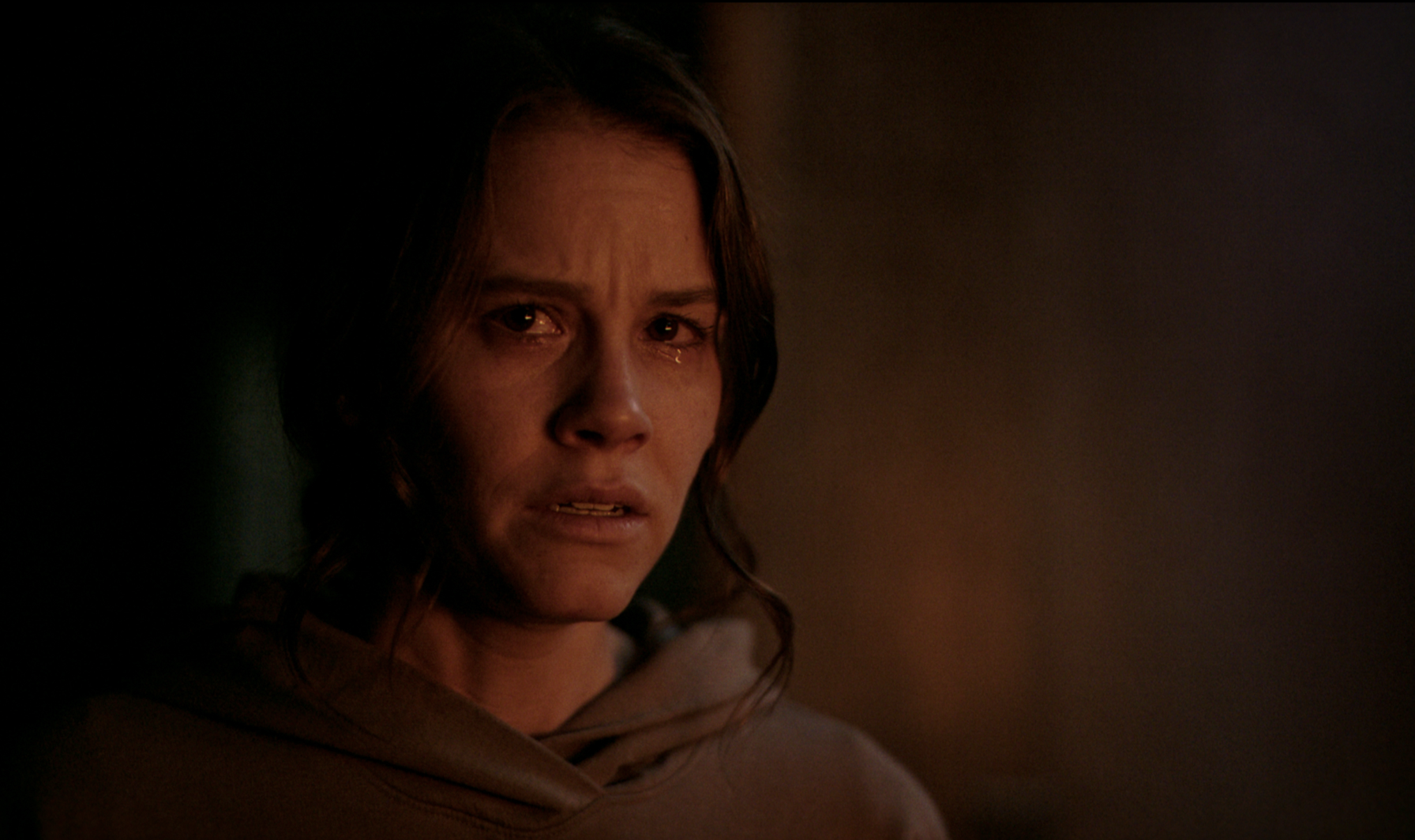

Additionally, where the film lacks conceptual cohesion, Sosie Bacon delivers in her forceful performance as Rose. It is no easy feat to convincingly play the role of the doubly trauma-stricken clinical psychiatrist, but Bacon does so with ease, teasing out the nuances of the psychological terror of trauma through her performance. Without Bacon’s skillful acting, the film would not have had the capacity to take on even the narrow conceptual berth that it did.

If anything, the last decade of horror has marked the beginning of the genre’s shift away from the tangible terror of slashers and other forms of classic horror and towards a mainstream of psychological horror. Although Smile does not deliver in the capacity that titles such as Hereditary (2018) or Get Out (2017) do, it serves as a stepping stone towards a new horror, one characterized by a conceptual inclination and varied in the premises allowed into its mainstream.