The class action lawsuit against 17 of America’s elite universities, known as the 568 Presidents Group, continues almost a year after it was first filed on Jan. 9. Throughout the lawsuit, the plaintiffs, who were former students of several of the universities, have alleged that the 568 Group overstepped the boundaries of an antitrust exemption passed in 1994 by failing to admit students on a need-blind basis. On Sept. 30, the exemption expired, leaving no excuse left for collusion. Now, as the lawsuit continues its fight to hold colleges accountable and seek significant financial damages, supporters are encouraging students to speak out and prevent the exemption from being reinstated.

On Nov. 11, the Voice met with Robert D. Gilbert of Gilbert Litigators & Counselors, one of plaintiffs’ lead counsel, for a discussion on the lawsuit and the exemption’s expiration.

“Defendant universities never complied with the Congressional mandate that they be need-blind regarding all students and all families in admitting students,” Gilbert said in a statement to the Voice. “Instead, for decades they exploited the exemption to favor wealthy applicants and families, and to disfavor applicants from middle class and working-class families.”

The exemption that recently expired, colloquially known as the “568 Exemption,” was originally included as a provision in the Improving America’s Schools Act of 1994, and allowed need-blind colleges to use common formulas to decide financial aid. The ongoing lawsuit argues that the 17 universities misused the 568 exemption in violation of U.S. antitrust laws, resulting in reduced financial aid and higher tuition prices. The lawsuit aims to obtain 19 years of damages for over 200,000 plaintiffs, and according to the lawsuit’s website could grant an additional $4,493 in financial aid to each eligible Georgetown student.

Despite frustrations with the 568 Group, the plaintiffs’ head lawyers are optimistic after the exemption expired, and look forward to seeing changes in the ways these institutions approach admissions.

“Now that ‘Section 568’ has expired, we look forward to seeing true competition on price by these elite universities,” Ted Normand of Freedman Normand Friedland, another lead counsel of the plaintiffs, said in a statement to the Voice. “Defendants are and should be leaders in providing high quality affordable higher education, so we expect to see beneficial ripple effects across America’s other colleges and universities.”

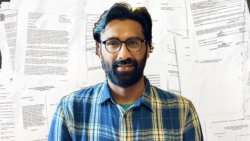

Although Georgetown has a relatively small endowment as compared to other elite universities, the university plays a central role in this narrative, as Georgetown President John DeGioia is also the president of the 568 Group. Sahaj Sharda (SFS ’20), currently a law student at Columbia University, shared his thoughts on DeGioia’s involvement in an interview with the Voice.

Sharda’s upcoming book, “The College Cartel,” takes on the question of why inflation and tuition costs at elite colleges are so high. He argues that collusive, anti-competitive structures in the submarket of elite colleges account for these issues in higher education. Eliminating these structures is central to the ongoing lawsuit, and it requires addressing the role of university administrators, including President DeGioia, who play a key part in keeping these systemic structures intact.

“[DeGioia] plays a really important role in keeping [the 568 Presidents Group] together. And so this is something that I feel very strongly about,” Sharda said. “I think that if President DeGioia has the courage to admit that what Georgetown has been doing for all these years has been wrong, there’s still redemption to be had.”

Sharda said that Congress reauthorizing the antitrust exemption would put an end to the ongoing class action lawsuit. “I think that the elite colleges might really flex their muscles on Capitol Hill and get a bailout from Congress whereby there’s a new exemption that’s resurrected that makes a lot of these things retroactively applicable so that not only can schools collude, but they don’t even have to do things on a need-blind basis.”

He points to net aggregate lobbying spending in education, claiming that elite higher education institutions are some of the biggest lobbyists. Statistics support what he calls a transactional relationship between legislators and the elite colleges. “I think Harvard spent something like half a million dollars a year just lobbying legislators. And it has nothing to do with the soft power that the institution has. So when the president of Harvard wants to get a meeting with Senator Schumer, the door swings wide open.”

Georgetown itself spent $270,000 in 2022 on lobbying efforts, according to OpenSecrets, a D.C. research and financial transparency nonprofit that tracks the lobbying money trail.

Sharda emphasized that without student awareness and involvement, it is likely that the exemption will be resurrected due to the colleges’ influence over Congress through lobbying and personal relationships. He claims that undergraduate voices are vital in preventing elite universities from colluding on price, and that the priorities of young voters are influential on the actions of legislators especially due to the impact of young voters’ support in recent elections.

“I think that if [legislators] take young voters for granted on an issue that deeply affects young people, not just for the four years that they’re in college, but for the rest of their lives, I don’t think that they will necessarily be able to depend on young voters,” Sharda added. “I think it’s time for the Democratic party to put up or shut up. Young voters bailed them out, and I think we expect the Democratic party now to deliver.”

He added in a later statement to the Voice that students can join the effort by signing his change.org petition, calling their home state senator or congressperson, and organizing protests.

“This won’t change without student activism and involvement, and that’s why I implore students to do everything they can,” Sharda concluded. “Change happens one person at a time.”