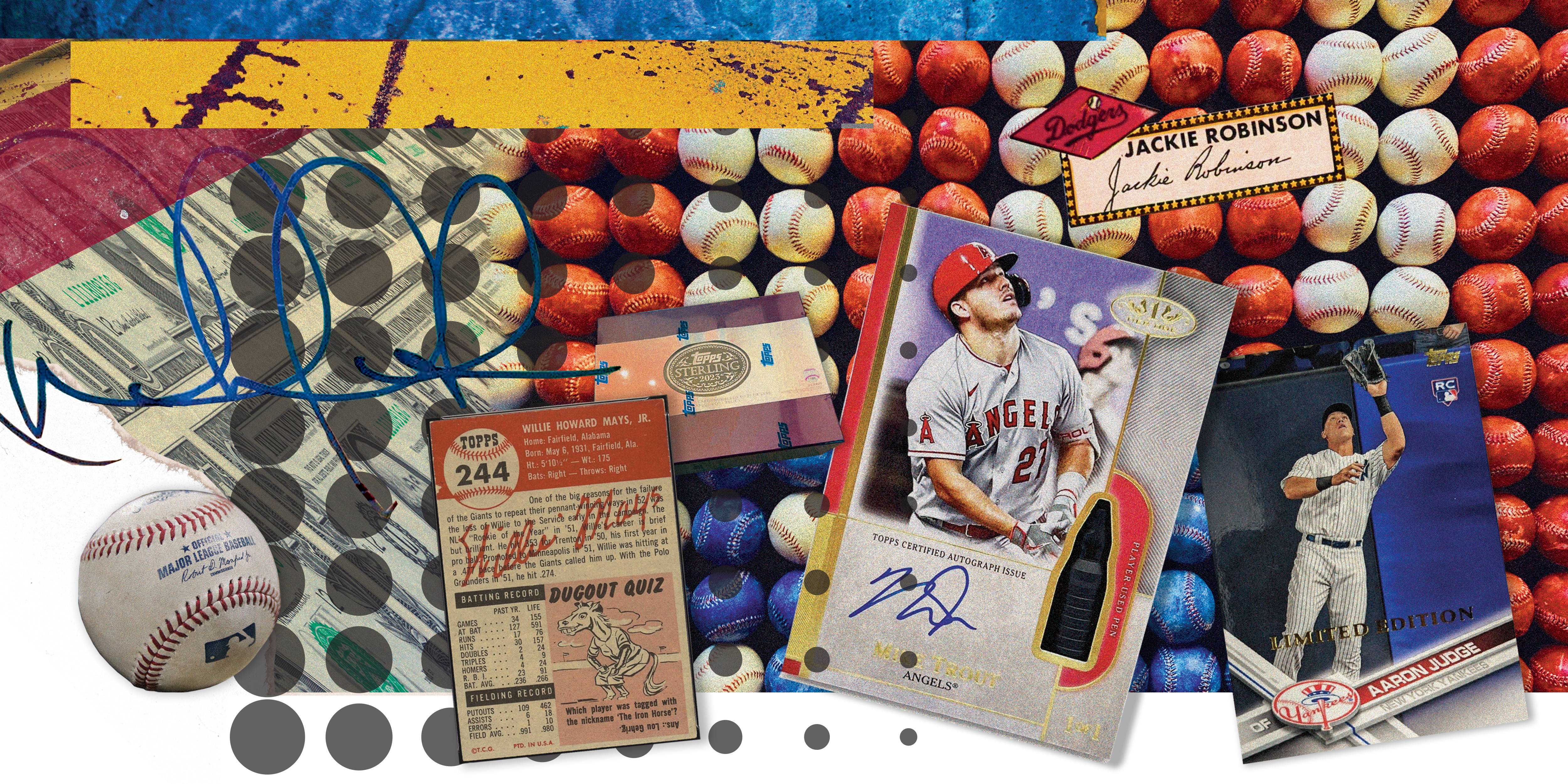

There’s an indescribable feeling that only comes with opening a new pack of baseball cards and the treasure that could be inside. Fingers trembling with excitement, the crinkle of the plastic wrapping only adds to the eagerness. Could I get an Aaron Judge autograph card, or maybe a Shohei Ohtani? As the cards are pulled from the wrapper, images emerge: snapshots of triumph, an instant of maximum effort, all frozen in time. Facts scrawled across the glossy backs: a player’s bio, their stats, their entire careers condensed to 3.5 inches.

A full set of cards used to act as a yearly almanac for Major League Baseball fans. Now, a lot of “collectors” don’t even bother turning the card over. Even fewer save the cards for their enjoyment. It’s all about the investment and the eventual sale. Maybe it’s a sign of the times: the nicer the cards are, the less people want to keep them. Or maybe it’s something else: the people most likely to treasure something as simple as a baseball card of their favorite player aren’t the same people who can afford to buy it anymore.

It’s becoming difficult to avoid the consequences of increased profitization across America. Yes, I know profitization is not a word, but I’m at a loss trying to describe the avarice of capitalism that has engulfed every facet of this country. Corporate profits are at an all-time high, customer satisfaction is nearing an all-time low, and the middle class continues to be squeezed into extinction. Corporate greed shouldn’t have anything to do with baseball cards, but it does. And that’s the point. The profitization of baseball cards, a universal collecting hobby, is the perfect encapsulation of modern American culture.

The card collecting hobby, on its surface, seems pretty straightforward. It’s about collecting the cards of players, usually printed on 18-pound cardboard or plastic. The cards come in packs which one can open to hopefully get the players they want. A lot of the fun in opening a pack of cards is the mystery; it’s better than going to the store and buying just one card you see on the shelf.

The company that’s stocked the shelves with card packs is Topps—becoming synonymous with the hobby as the biggest producer of baseball cards for decades. But after a buyout by Fanatics, the support for Topps among dedicated fans has waned. Baseball cards were already getting more expensive, but rising prices combined with Fanatics’s public missteps in the baseball card world has resulted in boxes of baseball cards collecting dust on the shelves of retail stores—a sign of corporate greed’s deteriorating effect on consumer loyalty.

Consumers bought and treasured these cards because they were snapshots of the past, providing insight into the evolution of American culture and design: the beautiful, realistic profile paintings of the 1953 set, in stark contrast to the photographs used in most years; the floating player heads of the 1960 set, when the cutouts were still done by hand; the distressed border framing player action shots in 1995, evoking successful contemporary grunge albums like Nirvana’s Nevermind (1991) and Pearl Jam’s Vitalogy (1994).

The major break in the linear progression of the cards’ pricing came about in the early ’90s. For decades, the price of packs stayed mostly the same. A five-card pack cost a nickel throughout the ’60s and a 10-card pack cost 10 to 15 cents in the ’70s; even by 1991, a normal pack of cards was still just 50 cents. Other than some short print cards, a couple of extra sets for players that had been traded, and the total number of cards in the “flagship” set year-to-year, that was everything that came through the printing press. How quaint.

Then Topps started inserting limited-edition “Topps Gold” cards into their packs, which included cards with gold-foil accents stamped on the player’s name and team. As prices began to increase, Topps added fuel to the fire by debuting premium sets, starting with “Topps Finest.” By 2016, Topps was offering a new “super-premium” product. Called “Topps Transcendent,” it costs $25,000 (the equivalent of 50,000 card packs in 1990). The reward for such a gaudy purchase? Numerous exclusive parallels and autographs, as well as a VIP invitation to a major Topps event that features a superstar player with the opportunity for photos and autographs. The hotel stay is included, but the flight—Topps isn’t a charity after all—is not.

The “Topps Transcendent” collection feels like the “jumping the shark” moment when the baseball cards officially passed the point of being an accessible hobby and instead turned into just another industry for people with too much money to sink their vast fortunes into.

Maybe it’s always been this way, and I’ve just been naïve. But my dad used to wrap rubber bands around his baseball cards and cherish them all the same. He didn’t care about crimping the corners or damaging the surface of the cards to preserve their resale value. Neither did the kids who kept their cards in bicycle spokes to make their bikes sound like a Harley-Davidson motorcycle.

But that’s not the hobby anymore. Modern collecting is now clearly separated by different tiers of products from different manufacturers, from the entry-level to the premium and even the super-premium. Topps has created a barrier to entry based on wealth. Unsurprisingly, premium boxes have come to dominate the hobby, and the most sought-after cards, such as cut autographs of players like Babe Ruth, come from boxes outside the price range of the average collector.

The modern hobby also features a new format that exploded during COVID: breaking. Sports card breaks are when a person, known as a “breaker,” buys an entire box, but instead of opening it and keeping the cards for themselves, they sell spots to other individual collectors to “buy in” to the box. Instead of spending $300 on a box, for example, a collector only has to spend $20 for a single spot. The collector is randomly assigned a team for the break, and they receive any opened cards which feature a player for the designated team.

The whole breaking format is not a fad. “Unboxing” content is huge across Twitch and Youtube, with four of the 10 most popular YouTube channels in 2021 starring kids unboxing new toys, and breaking builds off the hype of watching the unknown become familiar. Breaks are also the clearest form of gambling the hobby has seen, with TikTok taking the step to ban live box breaks over worries that the practice constituted illegal gambling. Fanatics so far has ignored concerns, deciding to lean heavily into breaking and the potential profits it represents. Fanatics announced Fanatics Live, providing a platform for “breakers” to host live videos of opening packs. The most recent editions of Topps merchandise now feature better odds for valuable cards in the boxes that are bought and sold by breakers rather than those available to an average collector. The decision has been controversial, to say the least, as some high-profile breakers have been embroiled in numerous scandals relating to stealing high-value cards from those that buy into their breaks.

But Fanatics CEO Michael Rubin is no stranger to controversies. A recent unboxing video with superstar soccer player Antoine Griezmann raised eyebrows as both men managed to pull expensive cards in back-to-back boxes: Rubin’s pack featured a one-of-one Mike Trout autograph relic card—worth at least $4,000—and Griezmann pulled a one-of-one Jackie Robinson autograph card—worth around $10,000. The odds of pulling the one-of-one Jackie Robinson is one in 8,034 packs, and the one-of-one Trout is one in 8,228 packs. The odds of the pair being pulled in back-to-back boxes? Ludicrously rare—enough to warrant accusations of loaded boxes. But I know if I was still a kid watching that miracle unfold, I’d run to the nearest Target and clear out the shelves, chasing a similar-quality card and helping Fanatics reach their sales targets in the process.

Fanatics is the future of the hobby in the U.S. because it will soon be the only game in town for licensed cards, and even the appearance that it is unfairly distributing its strongest cards and boxes undermines the integrity of the hobby—although Rubin has theoretically promised to be more transparent. Associations with unfair practices can and likely will hurt the value of boxes. After all, few people will spend money on a product where the best cards have already been taken out of circulation. As Fanatics continues to try to corner the sports memorabilia market, collectors may not have any other options.

Players come and go, but the greed that left the regular Joes of this country in the dust will always find a new form of conspicuous consumption. It’s been seven years since “Topps Transcendent” started, and yet the boxes have sold out every year. There will always be a bigwig who can spend more on a box of cards than a federal minimum-wage worker makes in a year. There are still people with both the money and the desire to pay whatever it costs, meaning Fanatics has no real incentive to change their strategy.

Talk to any normal collector or read any message board and it becomes obvious that the connection between collectors and the hobby has been broken at some level. How many people, when faced with eye-watering prices and unfair card access, let go of their passion that first drew them to collecting in the first place?

I think of all the kids who will grow up loving sports but miss out on the added joy of showing that love through collecting. It’s not a stretch. If you were born before the ’90s, the best cards available were the only cards: the Topps flagship set. The cost per pack was the same for everyone. A kid and their parent could each open a dozen packs for just over $10 and have as good as odds as anyone to get the big rookie. People have to pay breakers to do that now.

At some point, greed trumps love. When a card isn’t just a collectible of a favorite player but rather an investment, you lose sight of what makes the hobby fun. Checking the stats for players becomes less about hoping your player succeeds for the thrill and more akin to watching the stock market rise and fall. Everybody has a breaking point where they can no longer stomach the cost—I still haven’t hit mine yet, since my passion continues to keep pace with my wallet. I sit content with my collection of cards, a mix of Yankees and a few of my favorite players from other clubs—nothing worth thousands of dollars, at least price-wise. Just like how the sets of Topps cards used to be snapshots of seasons past, each of my cards is a snapshot into my life: moments from opening cards at Christmas, a purchase at my local card shop, a card I got signed in-person. A lot of the cards on my shelf likely won’t ever be priced at more than a few hundred bucks, but to me, they’re worth more than that, no matter what eBay says. I just have to think back to one of my dad’s favorite sayings: “Always remember what you have that is valuable. Because you will meet a lot of people in this life that know the price of everything and the value of nothing.”

I’ve been collecting since 1975 I quit buying g boxes about 5 years ago. I have a friend that buys and I buy what he doesn’t want. And I buy my new team sets on ebay. I got priced out. So I’ve been buying vintage sets. It’s the way to go I’m 1 card away from competition of my 1969. I love buying vintage hall of farmers. I don’t get caught up with the next super star . That people spend big money on that never pans out or pull a wander Franco. Yes I’m a set builder I’m complete from 1969 to present. I’m on trade group in Facebook that helps me finish my sets alot. I hated panni good riddance. Love Topps. But like I say I will never buy another box. Been burned way to many time

Great article and we to draw more attention to, what I believe to be, predatory pricing strategies and business practices by the major sports and entertainment trading card producers. A handful of companies hold the IP rights which limits competition. They manipulate supply further driving-up prices. The packaging for the cards is very misleading and designed to manipulate the perception of consumers. Good luck finding certain brands such as Garbage Pail Kids at retail stores. The only way to purchase is via the production company’s website and purchases are only permitted within short periods of time. Additionally, often times there’s no limit to the number of purchases an individual buyer can make. And because supply is limited the product quickly sells out which means the only way to obtain the product is through 2ndary markets like eBay diving costs even higher! By far number 1 on the list is Topps, especially since its acquisition by Fanatics. I encourage people to research Fanatics leadership team, execs, and Chief Officers. I’m all for capitalism and understand the importance of profitability. This homogeneous group of people have (yet again) hijacked a once affordable source of entertainment, abuse the liberties of a free market economy, manipulate the protections offered by corporations, lock-up as much of the IP as possible. Keep in mind these people create nothing, they work the system and leverage.

Growing up in the early 70,’s it was fun to walk down to the corner deli and pick up a pack for a dime and eagerly open the wax pack as the heavenly scent of fresh bubble gum was released. I was so eager to see if I got a super star player. Today cards are for dealers to cash in. No gum. No fancy borders, just stock photos of players in action. No more cheesey poses of pitchers pretending to go through their wind up. I wish there was another card company that produced cards like that with gum At a price kids afford.

I just got access to my 1980s early 1990s baseball cards that my dad collected, and they have been in a safety deposit box up until recently I wanted to see what I had and bought one thousand penny sleeves and top loaders and one foot white boxes. I’ve realized I have a lot of error cards that some are one of one with printer Ink spots to wrong birthdays with miscut designs where the center picture should be 50 percent of the middle of the card with 25 percent on both sides, but I have insert or specials that are miscut or don’t have the dot after the inc in Donruss Leaf inc, but having it on a mark mcqwire rookie card or a Topps record breakers card ends up having a triangle that ends up making the card valued at $3,000 and up but knowing its been opened and quickly put up into a plastic case, the smartest thing you can do is get it I graded for the card to truthfully be worth its full value

.

I just got access to my 1980s early 1990s baseball cards that my dad collected, and they have been in a safety deposit box up until recently I wanted to see what I had and bought one thousand penny sleeves and top loaders and one foot white boxes. I’ve realized I have a lot of error cards that some are one of one with printer Ink spots to wrong birthdays with miscut designs where the center picture should be 50 percent of the middle of the card with 25 percent on both sides, but I have insert or specials that are miscut or don’t have the dot after the inc in Donruss Leaf inc, but having it on a mark mcqwire rookie card or a Topps record breakers card ends up having a triangle that ends up making the card valued at $3,000 and up but knowing its been opened and quickly put up into a plastic case, the smartest thing you can do is get it graded for the card t6oi truthfully be worth its full value. Just so⁷me cool things to add I have some Bo Jackson Cal Ripken Greg Maddax Ken Griffey and You’ll notice how there was no way to know those errors would be rare or valuable ad there was no Internet. but having 6 out of 10 rookies that have 3 errors on 6 out of 10 of them, and it just doesn’t make sense the odds and rarity when I seem to have error cards in every year of 1985-1992.

.

Absolutely great article and spot on