“1, 2, Freddy’s coming for you…”

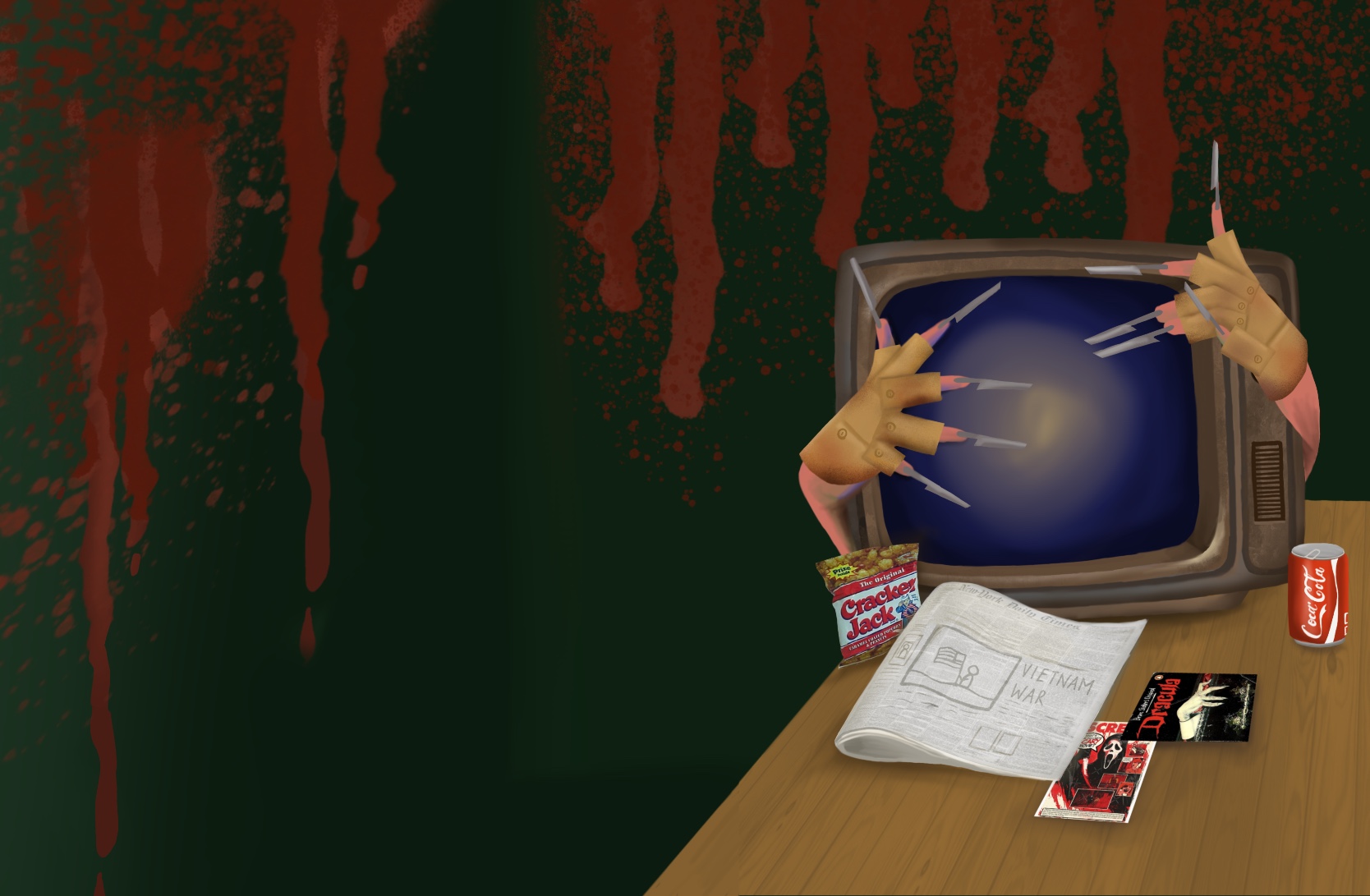

Released in 1984, Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street left a permanent mark on the horror genre and popular culture. It spawned countless slasher tropes, seven total sequels and reboots, and an invasively catchy nursery rhyme parody that countless children recite before knowing its origin. Most notably, it introduced the iconic figure of Freddy Krueger (Robert Englund), and normalized the violent reprobation of teenage delinquency that would become a mainstay in the genre for the next several decades.

Because Nightmare was so influential on its successors, it can feel cliché in retrospect; modern audiences will recognize many of its tropes regardless of whether or not they have seen the source material. The film’s mainstream success enabled Craven to widely share his observations on American culture, influencing countless genre movies from Craven’s self-parody Scream (1996) to David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows (2014). This cultural legacy is ultimately more than enough to cement Nightmare as a classic.

“3, 4, better lock your door…”

Nightmare’s tone oscillates from suspenseful to comedic to horrific as Craven carefully imbues each scene with emotional affect. The film opens on a shot of Krueger assembling his infamous razor glove in a gritty industrial setting, with close-ups used to cultivate a feeling of claustrophobia. Despite the revelation that this sequence was simply a dream of Tina’s (Amanda Wyss), jagged cuts have manifested on her nightgown in real life. Nightmare frequently blurs the line between dream and reality, instilling a sense of constant paranoia as the audience questions what is real or imagined.

Because Nightmare is a slasher, it, of course, has kills; and, since it follows in the tradition of predecessors like Halloween (1978) and Friday the 13th (1980), all of the kills have morals. Despite learning that the rest of her friends also had nightmares about the gloved murderer, Tina quells her fear and decides to sleep with Rod (Nick Corri), solidifying her place as the first victim of Krueger’s violent didacticism. In Tina’s next dream, Krueger compares his glove to the “hand of God,” capable of executing judgment unrestrained by human laws. He kills Tina in her dream, while in real life, an invisible force rakes wounds across her chest. Rod—now the primary suspect in Tina’s murder—is next to go, leaving Nancy (Heather Langenkamp) and Glen (Johnny Depp) in hysterics over their friends’ gruesome deaths. Without a rational explanation beyond her dreams, Nancy is steadfast in her conviction of Krueger’s existence. Her unconvinced parents install bars over her windows, however, trapping her in a house of nightmares.

“5, 6, grab your crucifix…”

At this point, the main antagonist effectively becomes Nancy’s parents. This fact is cemented by revealing Krueger’s origin: a child murderer who escaped prosecution and was killed by a mob of concerned parents, including Nancy’s. Despite acknowledging their responsibility for Krueger’s death, Nancy’s parents seem unable to comprehend how their actions have endangered their daughter and her friends. The parallels to issues like the Vietnam War, economic recession, and the climate crisis are both implicit and timeless—parents are willfully ignorant of the effects of their decisions on the next generation, good intentions be damned. Nightmare’s critique of traditional sources of protection is not limited to parental figures. In one dream sequence, Nancy ventures into her school’s basement, revealed to be the setting of the opening scene. The canker that haunts her dreams quite literally undergirds American pedagogy.

“7, 8, never stay up late…”

Though it may seem cartoonish and over-the-top, the violence in Nightmare is deliberate. Craven is an incredibly intentional filmmaker, juxtaposing emotional affect with slapstick comedy. The themes of senseless cruelty, teenage dejection, and the failures of American government are present throughout Craven’s filmography, particularly in his first endeavor, The Last House on the Left (1972). Both films mimic the violence of the Vietnam War, the Kent State Massacre, the Manson murders, and other contemporary atrocities rooted in intentional abuse or gross negligence from American bureaucracy. Nancy’s father represents more than just parental shortcomings; as the chief of police, his refusal to heed his daughter’s warnings allows more preventable deaths to occur. For Last House, Craven felt that fictitious depictions of violence should reflect brutal reality in light of the ongoing conflict in Vietnam, writing a script that was incredibly graphic and explicitly pornographic. The film follows a teenage girl who is kidnapped, tortured, and murdered by a family of killers, and is avenged by her parents. One of the first American entries in exploitation cinema, it was banned in several countries and censured by critics for its overt violence.

Despite their thematic similarities, the two films have been remembered in the collective consciousness very differently. Nightmare holds mainstream classic status while Last House garnered a more niche cult following several decades later—a dichotomy which speaks to the somewhat arbitrary nature of “classic” films themselves. Craven received cult recognition as a cultural commentator by spoon-feeding through metaphor in the commercially-successful Nightmare on Elm Street rather than the brutal realism he originally pioneered in Last House. In 2023, Last House feels like a much more modern horror film, particularly in light of the 2000s torture porn genre, while Nightmare feels charmingly dated. In the ’80s, we wanted brutality to be confined to our nightmares—not our neighborhoods.

Nevertheless, Nightmare’s prevailing influence in pop culture is sufficient to justify its classic status. The film is ripe with terrifying fantasy scenarios that intelligently comment on the horror of life in the ’80s. The tonal shifts in the narrative contribute to the thematic conflict between the notion of the American Dream and the lived experience of ’80s teenagers who were confronted by American militarism and a domestic economy that promised less prosperity than their parents had enjoyed. Furthermore, the film’s violence feels morally charged rather than arbitrary—transgressions must be punished to uphold the status quo. As Glen comments early on, “morality sucks,” but even still, it won’t save you from senseless violence. The brilliance of Nightmare is its inversion of the American Dream through sadistic allegory, personifying our greatest fears.

“9, 10, never sleep again.”