Three professors in the Arabic department are on leave this semester after current and former students made allegations of racial and religious discrimination and harassment in the classroom.

The Voice spoke with four students who said they were treated unfairly by the professors because they were Arab, Muslim, or Black. Three of those students filed bias reports against professors Hanaa Kilany, Ghayda Al-Ali, and Huda Al-Mufti with the Office of Institutional Diversity, Equity, and Affirmative Action (IDEAA) last academic year. The Voice spoke with three additional students who corroborated their stories, and three others who said they witnessed discriminatory behaviors by these professors aimed at other students.

Fifty-four of the professors’ former students and teaching assistants came forward in the professors’ defense this September, signing a petition to Provost Robert Groves dated Sept. 4. Idun Hauge, a Ph.D. candidate and a former student of Kilany’s who wrote much of the petition, told the Voice that its intention was not to deny the allegations but to say that they themselves had not witnessed any discrimination, and criticize a lack of transparency around the case.

The university declined to comment on whether the professors are on leave for reasons related to the student complaints. None of the professors responded to the Voice’s requests for comment, and IDEAA mandates confidentiality for investigations.

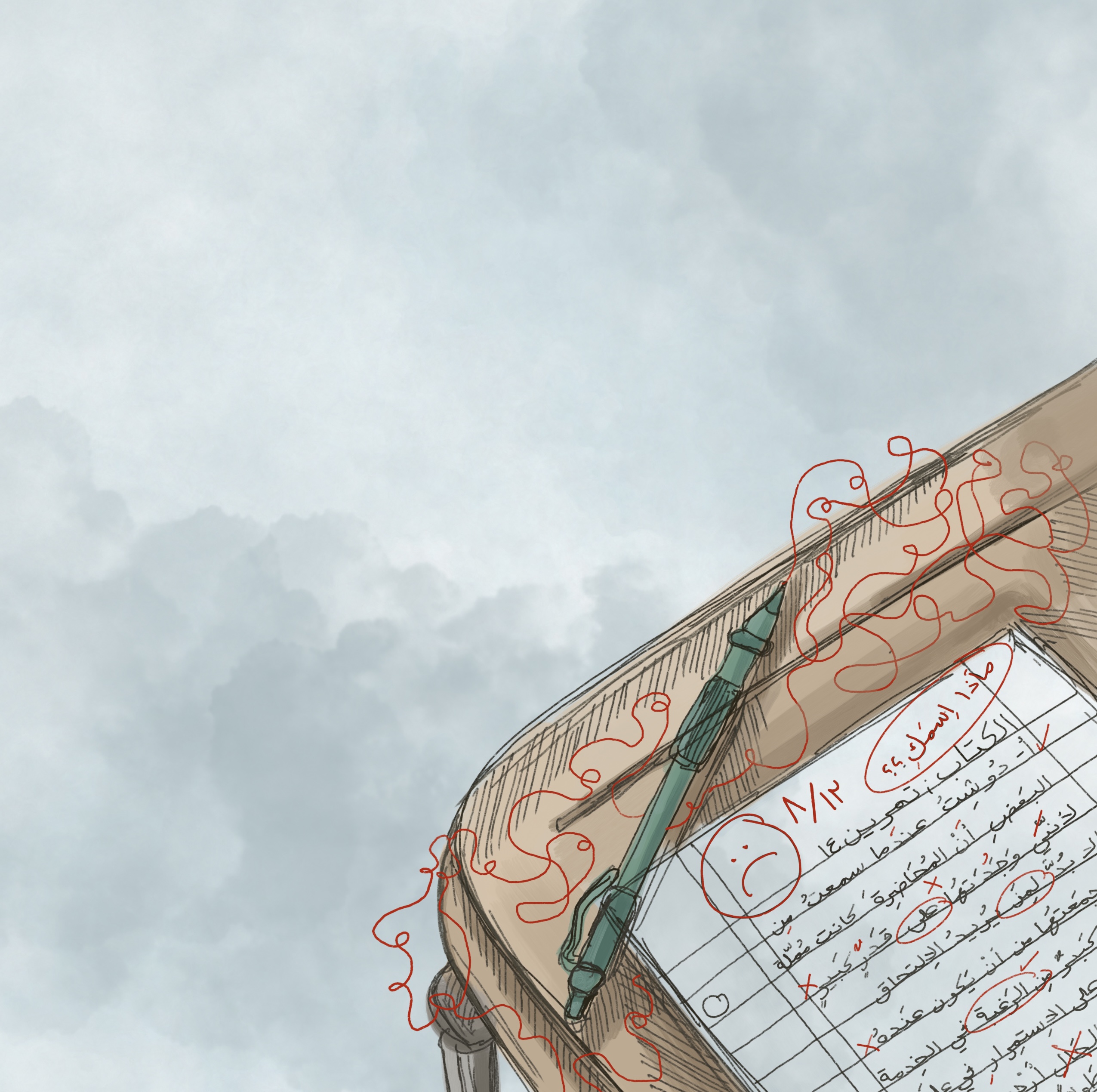

Students told the Voice they were singled out in class and were harrassed with questions and comments because of their ethnicity, race, religion, and/or appearance. They said they were held to different academic standards than their white and non-Arab peers.

Some of these experiences were first made public in a widely circulated letter from the Muslim Student Association (MSA) in November 2022. “The Arabic Department at Georgetown has systematically discriminated against students of color, both in individual cases of racial targeting and abuse—including the use of racial epithets in Arabic—and in systemic failures of inadequate procedures to allow students to take proficiency exams required to graduate,” the letter reads.

The letter asked that the students who alleged discrimination have the opportunity to have their grades repealed or audited. It also called for consistent and clear standards across the department, reviews of the proficiency exam guidelines, and “bias training specific to teaching Black, Brown, and Muslim students,” among other changes.

On Dec. 5, IDEAA reached out to five students, three of whom said they filed bias reports and two others who said they were involved in collecting student responses of personal and witnessed experiences through a Google Form attached to the MSA letter. In the initial email to the students, IDEAA determined it would “conduct a formal review of issues through the administrative review process.” In a follow-up on Feb. 1, an IDEAA representative said that they had begun that process, according to emails obtained by the Voice.

IDEAA soon began reaching out to students for interviews as part of the investigation, according to Justin Liu (CAS ’24), who took language classes with Kilany and Al-Mufti and was among the five students initially in contact with IDEAA. “Literally everybody I know in that department had one of those meetings,” he said.

Another of the five students, Mohammad Lotfi (SFS ’23), said he filed a bias report against Al-Ali in November 2022, and is a former student of Kilany’s. He said that the Arabic department’s prestige was a major reason he transferred to Georgetown his sophomore year, but that he ended up dropping out of the department because of his experiences.

Lotfi took a virtual intensive Arabic language class with Kilany during his sophomore year. He described being repeatedly singled out in class, being asked to read religious passages out loud when no other student was asked to, and being told “That’s not Arab” after saying his family was from Morocco.

Lotfi said that he was also singled out and discriminated against in an Arabic language class taught by Al-Ali during his senior year.

“There were four other kids [in the class] and they were all white, from the United States,” he said. “[Al-Ali] would snap her fingers in my face. She would close my laptop on my fingers. She would rip papers out of my hands.”

He said the professor would skip over him every time she asked questions because she said she knew he was not going to answer correctly, and that she gave him a zero for participation. He recounted being held after class and told, “‘Mohammad this is embarrassing. Would you please not talk in class?’”

“She told me she would fail me out of the class if I didn’t attend mandatory office hours but not all the other students were required to go,” Lotfi said.

Lotfi said Al-Ali also asked him to read parts of the Qur’an when no other students were asked to. He said that she told him that “with a name like Mohammad, you should know how to read the Qur’an.”

Concerned about his ability to pass the Arabic proficiency exam based on his experiences with Al-Ali and Kilany, he wrote a letter to the Academic Standards Committee. He was told by the committee to file a bias report.

“I submitted it and that Monday, I think, we all came back and [Al-Ali] said, ‘Okay there’s a new vocabulary word: accused, itahama.’ She immediately turned to me and said ‘Mohammad, can you say, ‘Ghayda Al-Ali was accused of racism and Islamophobia against Muslim and Arab students’ in Arabic?’” he said.

The Muslim Student Association letter began circulating around the same time, and Lotfi later joined the four other students, including Liu, in communication with IDEAA.

“I don’t want people to think that around the time of the letter, there was some sort of big change of opinion against the department and that students were suddenly experiencing discrimination. It’s something that’s been happening for a long time,” Liu said. “We all bet that maybe no one in the past has organized to this degree before, and that’s the thing that’ll change things.”

The Voice spoke with two other students who filed bias reports, who spoke under the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

One of the students, an Arabic minor, said she filed a report against Al-Mufti. Although she took classes with Al-Mufti one semester of her sophomore year, she said she only filed a report her senior year because she feared retaliation. The student, who is Black and a heritage speaker, said she was singled out by the professor.

“My experience in that class, the intensity of what was going on, was so obvious because even my classmates would reach out to me during and after class,” the student said. Student messages from her class’s GroupMe chat apologizing for Al-Mufti’s behavior were reviewed by the Voice.

After a conversation with a friend, the student said she found out her experience with Al-Mufti was similar to what the friend had experienced with Kilany. After hearing about the MSA letter and similar incidents from multiple friends, some of whom graduated years before, the student joined other students in communicating with IDEAA.

The Voice spoke to the aforementioned friend, an Arabic minor who also said she filed a bias report against Kilany in November 2022.

The student said Kilany constantly commented on her appearance and would call her by the wrong name or mistake her for other Black students in different sections. She also said Kilany would not accept her on-time assignments and marked them down with no explanation, causing the student’s GPA to drop. The student said Kilany continued to harass her throughout the semester, including touching her hair.

When the student mispronounced a reading in class on Nov. 1, 2021, she said Kilany made her stand up and criticized her Arabic in front of her peers, an experience the student described as humiliating. The Voice corroborated the incident by speaking with another student in the class and reviewing messages sent to the student by other classmates.

Ten days later, the student said the class was learning about colors and how to describe people. Describing people’s skin tones is different from describing actual colors in Arabic, according to the student. The professor pointed to the student, the only Black student in the class, and told the class to repeat what her skin color was. The student said the word Kilany used was a racial slur in Arabic.

During the Fall 2022 semester, the student learned that three others said they also experienced discrimination in Kilany’s classes and didn’t feel their complaints to administrators and the department were taken seriously.

The student was contacted by IDEAA in the spring of 2023 for interviews. “I want accountability, and I don’t want any other Black student to face this again,” she said.

Another student, an Arabic minor who spoke with the Voice under the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation, said she faced similar experiences with Kilany.

She said Kilany told her she couldn’t wear ripped jeans in her class because, “you can’t wear that in the Arab world,” although other students wearing similar clothing were not singled out. She said that Kilany touched her hair, made comments about her hair in front of the class, and held her to different standards than her peers.

In one instance, the student said she wasn’t allowed to finish a quiz while everyone else got more time, and was not given a reason why. She also said that other students spoke up in her defense at the time of the incident. During a class presentation, she said she was not allowed to use notes because “you speak Arabic, you don’t need notes like everybody else.”

In an encounter with Kilany after a class, she said she asked why she was being treated worse than other students. The professor responded that the way she treated her had nothing to do with her race or ethnicity, she said, which she found odd because she had not ever suggested it was.

The student said she didn’t file a bias report because she didn’t think it would lead anywhere. She said Kilany minimized her grievances when she brought them up. Two classmates corroborated the student’s in-class accounts to the Voice.

“What really bothered me was that I felt like I was being judged and then held back almost for being Muslim and Arab in some of these courses because I was Black as well,” she said.

In the petition of support sent to Provost Groves in September, dozens of students and teaching assistants attested to witnessing no discriminatory behavior from any of the professors. Amani Aloufi, Ph.D., a former TA for both Al-Ali and Al-Mufti, wrote that she did not believe they would discriminate against anybody.

“Throughout my time in their classes, I have never encountered any instance that would lead me to believe that they engaged in discriminatory practices based on race or religion. It is my belief that these allegations do not accurately represent the character and values of

Professor Al-Ali and of Professor Al-Mufti,” Aloufi wrote. “I understand the importance of addressing any concerns related to discrimination seriously, but I firmly believe that the accusations against them are unfounded.”

Hatice Ozturk, a Ph.D. candidate and a former TA for Al-Ali and Kilany, wrote the same about their character.

“As a Muslim woman who has worked closely with these professors, I can attest to the exemplary treatment I have experienced, as well as witnessed towards other students,” Ozturk wrote.

Students told the Voice that they felt the petition invalidated their experiences, failed to take anti-Blackness into consideration, and dismissed the seriousness and scope of the IDEAA investigation.

“I was interviewed for six months, I mean, our lives were picked apart,” the student who filed a report against Kilany said. “In no way or matter can somebody say this wasn’t a qualified sort of investigation. And to say that is completely dismissive because you don’t know what’s going on.”

Students originally learned the three professors were not teaching this fall when they saw their absence on the registrar and in the course schedule. The professors are also listed as “on leave” on the Arabic department’s website though no announcement has been made by the department or administrators.

“As a student who wants to see justice in the department, I wish there was a university-wide announcement. I wish that the department sent out an email specifically to students in the department. I wish the replacement process was smoother,” Liu said. “If there’s not going to be any announcement or recognition of what happened, then there’s a chance this happens again in the future.”