Imagine doing the same thing every day. You’re a toilet cleaner with graying hair, living in the outskirts of Tokyo, following the same daily routine. You wake up to the sounds of a lady sweeping the streets outside your modest neighborhood. You get up without a fuss, drive to work with ‘80s cassettes in the background, clean some toilets, eat some sashimi, read some Faulkner, then sleep. You wake up and repeat that. And before you realize it, those are your days, and how you spend your life. You wouldn’t have it any other way.

Perfect Days follows Hirayama’s (Kōji Yakusho) monastic regimen across one week, proposing that simplicity and repetition can lead to spiritual fulfillment and possible enlightenment. The film starts off feeling like a slice-of-life, but as subtle disruptions break through Hirayama’s current continuum, we are thrown deeper into his reality and asked to contemplate the enduring questions that prevails all existence: why are we alive? How does one live?

Wim Wenders, acclaimed German New Wave director of Paris, Texas (1984), rejoins the cultural zeitgeist with Perfect Days, his first feature in six years. Released in the U.S. earlier this year, at first, the film presents a straightforward story about an old man bumbling around Tokyo with a philosophical appetite. However, the film takes a turn once Hirayama’s niece (Arisa Nakano) pays him a spontaneous visit, disrupting his comfortable routine. Later, as Hirayama’s high-society sister Keiko (Yumi Asō), well-groomed and acclimated to high-society, comes to pick up her daughter, the audience gets a window into Hirayama’s past. She’s aghast at Hirayama’s current living situation, which, viewed objectively, verges on impoverished. On the other hand, her life bears a certain tragedy: her daughter hates her, her husband doesn’t love her, but nonetheless, she must act poised in the face of hardship. We never do get the answer as to why Hirayama has chosen this lifestyle, but we are made to understand that there is a darker, more troubled past that he is treading above.

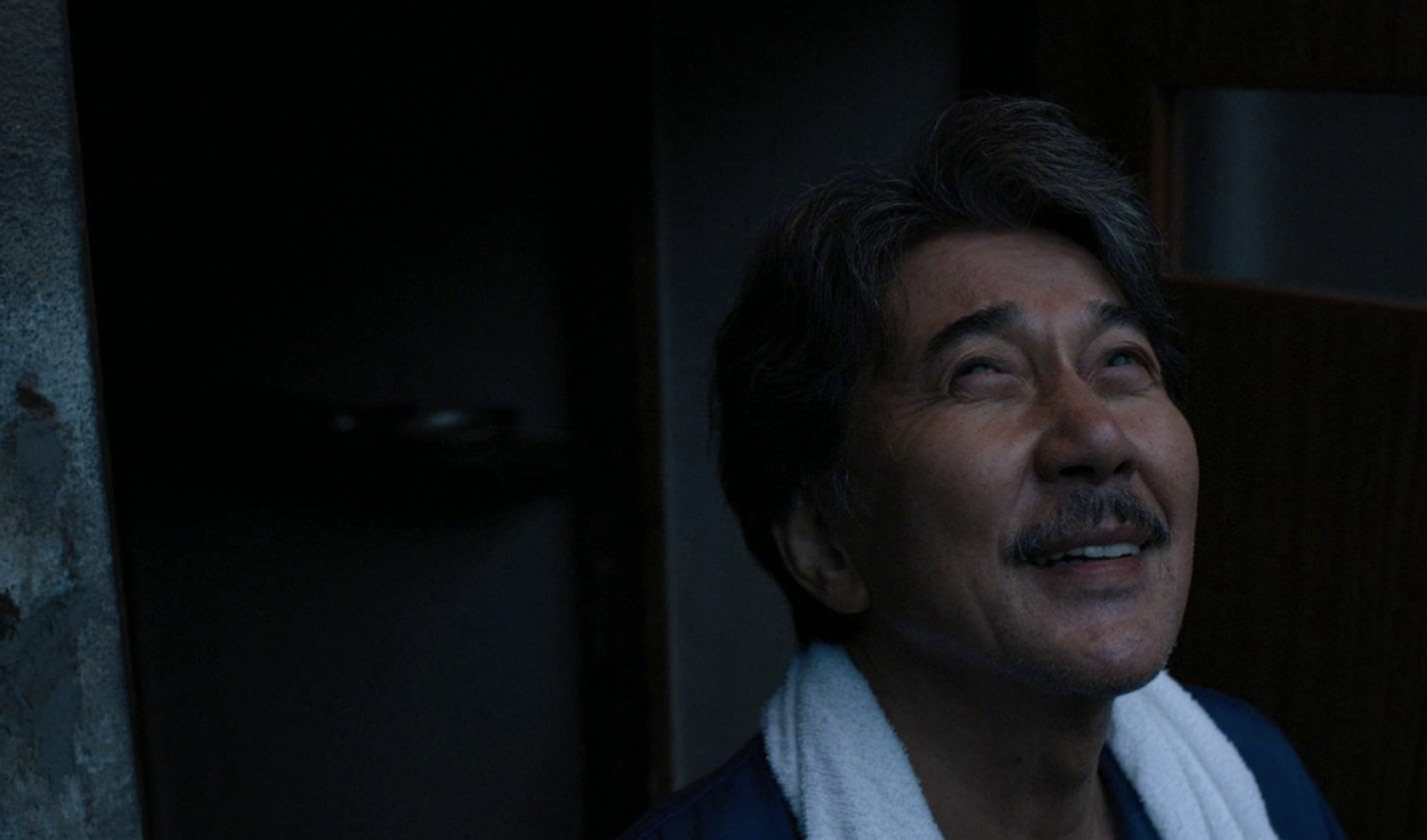

Hirayama’s days as a toilet cleaner are perfect not because of what happens, but because of what doesn’t. His routine is a daily prescription rather than an idyllic practice. There’s a darker undertone to this film—Hirayama has abstract, shadowy dreams where he grasps at something almost within reach before running away; the closing of his favorite restaurant spot drives him straight to the bottle; he rarely says anything, and if he does, it’s only one or two words at a time. All of his actions therefore act as a balm to heal his ambiguous past. Yakusho is at his finest here; playing a stoic role like Hirayama is no easy feat, yet his character comes to life through Yakusho’s minute movements, movements amplified through Franz Lustig’s cinematography. Ample close-up shots linger on the smallest muscle tremors on Hirayama’s face, the subtle movements intensifying as the film progresses. From the precious wrinkles by the sides of his eyes and mouth when he rarely laughs to the gauntness of his cheekbones, this is a film obsessed with the beauty of small details. These close-up shots effectively illuminate the subtle physical manifestations of Hirayama’s multifaceted emotional landscape which Yakusho is working so hard to bring to life. Hirayama’s persistent practice of waking and working in the face of past traumas is remarkable in its unremarkable presentation: this monotonous routine brings him sincere peace. Even when reflecting on suffering, Perfect Days urges us that the sadness will pass and perfect days will come again soon.

Director Wim Wenders layers Perfect Days with a myriad of religions and philosophies including Stoicism, Protestantism in Germany, and Zen Buddhism in Japan. At times, Hirayama’s characterization verges on hagiography; his calm energy sometimes transcends mere humanity, presenting him as a figure that has achieved an understanding of existence. This film is not just a linear depiction of someone who cleans toilets; it’s a broad depiction of a person who appears to have discovered, at least for the time being, a way to live a life without succumbing to anguish, where each day promises to deliver unbroken calm.

Perfect Days’s philosophical subtext reminds me of the Alan Watts’ essay “You Play the Piano” in which he asserts that the meaning of life is not some serious goal or answer. Rather, we all exist on one playful continuum. Oftentimes, our modern conception of a meaningful life depends on working towards some goal; Watts asserts that many people think of life like a journey with a serious purpose at the end such as success or heaven. However, using the motif of a piano, Watts insists life is a musical, playful thing rather than something strictly duty-driven. Watts contends mundane life is rife with meaning—meaning is found throughout life rather than just at the end.

The film transcendentally depicts life’s simplest experiences. When Hirayama’s taking a bath in the onsen, we see him in fetal position shot through a blurry side lens—do we see an old man nearing the end of his life or an embryo still in the womb? Or is our proximity to life’s inception or conclusion irrelevant compared to the beautiful sensation of enjoying a bath? Wenders turns the mundane into the ephemeral, helping us recognize the prestigious as inconsequential and the simple as precious. Wenders does not just tell us to stop and smell the roses; he presents his own philosophy on how to live life. Perfect Days suggests that a perfect day is one in which we learn to play with life and dance with the music.